Afterword

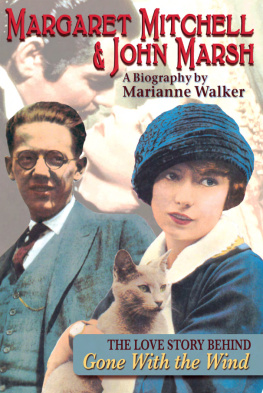

T HE PRIVET HEDGES in front of John Marshs house on Walker Terrace grew in tall, sprangling rows because he did not like to have them trimmed down into hard, compact walls. The shrubs were thick with blooms this spring of 1952, and their strong, sweet fragrance filled his rooms. Peggy had never seriously wanted a house, but it had been a long-held desire of his, and as soon as the estate had been settled, Margaret Baugh had gone house hunting for him.

She had helped him move into the charming one-story cottage on Walker Terrace just before Christmas, 1949. The house had an apartment attached to it, which Bessie Jordan occupied so that John need never be alone. In the three and a half years since Peggys death, he had lived a quiet but fulfilling life. Stephens had taken over most of the business of Margaret Mitchell, although John still kept his hand in on the foreign affairs. He had a number of friends who came by often to see him, and Margaret Baugh drove him wherever he wanted to go. His favorite entertainment was the opera and he looked forward to its arrival in Atlanta each spring, attending as many performances as he could.

In late April of 1952, he attended a performance by Dorothy Kirsten in Carmen with a young friend, Bill Corley. He was much enchanted with Miss Kirsten and, after leaving the theatre, told Corley, Thats my kind of woman!

The following Monday, May 5, 1952, John felt weary, for there had been several visitors over the weekend and he had remained up long past his usual bedtime. Bessie served his dinner and, thinking he looked peaked, told him he should go straight to bed. But he sat up reading rather late. Bessie heard him calling for help about 11:00 P.M. and instantly went to his aid. He had been stricken by a heart seizure. Bessie got him to the bed, called the doctor and an ambulance, and remained by his bedside until medical assistance arrived. But it was too late.

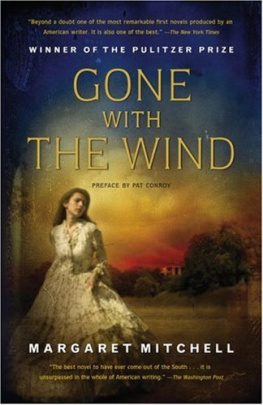

The mama and papa of Gone With the Wind were now both dead.

Margaret Mitchell had left all rights to Gone With the Wind to John Marsh. On his death, these rights passed to Stephens Mitchell. When asked once by an interviewer what Gone With the Wind was about, Stephens Mitchell replied, Not change and survival or war or its aftermath. Thats the background. It is the story of the inheritance of a certain characteristic, that characteristic being juvenile love for some man. [Scarlett OHaras] mother falls in love with her worthless cousin, who finally gets killed in a barroom. But she marries and is a faithful wife, builds up a big plantation for her husband, and dies with her worthless cousins name on her lips.

Her daughter inherits that characteristic. She loves her village beau, too, but she cant have him. And she will go through hell and everything else to get him. And then, after all these things have occurred war, pestilence, and so on she has her hands on him and all of a sudden finds out that it was just a juvenile fantasy.

And that is the crux. Its a psychiatric novel.

But the millions of readers of Margaret Mitchells Gone With the Wind would never accept Stephens Mitchells explanation of his sisters book. Nor would they agree that he is the keeper of the Margaret Mitchell legacy. For Gone With the Wind has become a part of our culture and, therefore, its legacy belongs to the people. Atlanta and its environs will evermore be known as Gone With the Wind country, and the words of the title, Gone With the Wind, will always reverberate with the defiance of a people whom Margaret Mitchell refused to let die.

In the vault of the Citizens and Southern National Bank, in a sealed envelope, are stored a few pages of the original manuscript of Gone With the Wind, preserved there as proof should the need for it arise of Margaret Mitchells authorship.

Stephens Mitchell professes that he has not examined the contents of the safe-deposit box where John Marsh placed the envelope, which is supposed to contain samples of his wifes manuscript with corrections in her own hand and special research material that would prove without a question of a doubt that Margaret Mitchell and no one else wrote Gone With the Wind. Back in 1952, Stephens said he had no intention of ever breaking the seal on the envelope unless requested to do so by tax authorities. This was never asked of him, and so those remnants of the writing of Gone With the Wind remain in the vault, the seal unbroken.

Why John Marsh and Stephens Mitchell felt someone might challenge Margaret Mitchells authorship of Gone With the Wind after her death is understandable, because Stephens, at least, had had to continue to contend with numerous lawsuits brought by unscrupulous people who wanted to trade in on the bonanza the book had made. But what is not so easy to understand is why they did not simply give the material to a university or library, so that scholars could have access to it and so that there would have been no question as to the books authorship.

The answer Stephens Mitchell gives is that his sister had wanted all her papers destroyed and, in fact, had a passion for leaving nothing in the way of close personal possessions behind her. He further states that she had told him she even wanted the house on Peachtree Street destroyed once he no longer cared to live in it, as she did not want strange people wandering through rooms that had once been hers. And that deed was done 1401 Peachtree Street was torn down in the 1950s shortly after Stephens Mitchells first wife, Carrie Lou, died.

Whether or not Gone With the Wind is a masterpiece has always been a matter of controversy. It is, perhaps, the most compulsively readable novel in the English language, a book that, despite its length it is as long as War and Peace has been read by people over and over again, and each time with great suspense, as though, somehow, this time the story might end differently. The book has survived the passage of many decades of world change, changes that have made much of the work of Margaret Mitchells contemporaries obsolete. But, ever since 1936, the South of the Civil War and Reconstruction periods has been viewed by Americans through Margaret Mitchells eyes.

Excluding the Bible, Gone With the Wind has outsold, in hard cover, any other book, and its sales do not seem to be diminishing. To date, the book has sold six million hardcover copies in the United States; one million copies in England; and nine million copies in foreign translation. Worldwide, it continues to sell over 100,000 hardcover copies annually, and 250,000 paperback copies are sold every year in the United States.

Perhaps the sales of a novel do not determine its literary qualifications, but its lasting images do. And who can now think of the South before, during, and after the Civil War without images drawn from the pages of Gone With the Wind? Scarlett seated under the shade of a huge oak, surrounded by beaus at the Wilkeses barbecue; Scarlett defying convention and dancing in her widows weeds with the dashing scoundrel, Rhett Butler; the hundreds of wounded lying in the pitiless sun, shoulder to shoulder, head to feet by the railroad tracks at Atlantas depot; the burning of Atlanta; Scarletts journey on the road to Tara; the moment when Scarlett claws the earth to take from it a radish root to stave her hunger; Black Sam and Shantytown; Mammy and her red petticoat; Prissy during the birth of Melanies baby; and oh, yes Scarlett OHara crying, What shall I do? when Rhett Butler finally decides to leave her and Atlanta, and Rhetts reply, My dear, I dont give a damn.

To Edwin Granberry, Margaret Mitchell once wrote, I didnt know being an author was like this, or I dont think Id have been an author. Her life after the publication of