Contents

Guide

Contents

For Amy

I see the moon,

And the moon sees me.

The Oxford Dictionary

of Nursery Rhymes

One never forgot the things she noticed, for she charged them with her own intense feeling. This power of enhancing and ennobling life was felt by all who knew her.

EDMUND WILSON ON ,

EDNA ST. VINCENT MILLAY ,

The Shores of Light

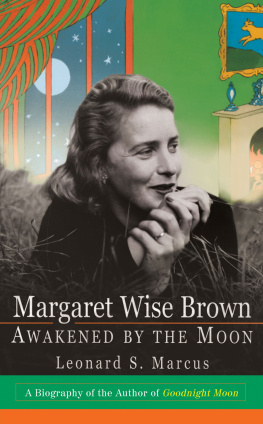

W e speak naturally, observed Margaret Wise brown, author of Goodnight Moon and other classics of the American nursery, but spend all our lives trying to write naturally.

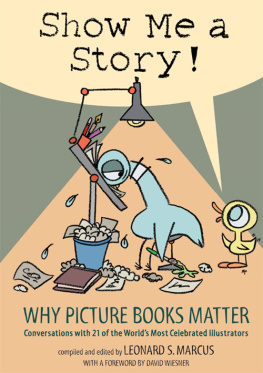

A contemporary of Ludwig Bemelmans, Robert McCloskey, Virginia Lee Burton, and Dr. Seuss, Margaret Wise Brown was one of the central figures of a period now considered the golden age of the American picture book, the years spanning the post-Depression thirties and the postwar baby boom forties and fifties. Bemelmans and the others began as visual artists who became authors, as it were, in order to have material to illustrate. In contrast, Margaret Wise Brown was a picture-book writer from the start, the first such writer, as Barbara Bader has remarked in her splendid America Picturebooks, to be recognized in her own right. The first, too, to make the writing of picturebooks an art.

Steeped in the moderns and trained at Lucy Sprague Mitchells progressive Bank Street school, she incorporated insights from these and other vital contemporary sources into a tireless personal campaign to make the picture book new. For a time she was a highly innovative juveniles editor, and throughout her career she played impresario to the entire field, taking pleasure in discovering or furthering the careers of illustrators and writers such as Clement and Edith Thacher Hurd, Garth Williams, Leonard Weisgard, Esphyr Slobodkina, Jean Charlot, and Ruth Krauss. It was at Margarets urging that Gertrude Stein wrote The World Is Round.

As she became increasingly successful, she used her growing influence to fight for juvenile authors and illustrators rights in their dealings with publishers. Widely respected by her colleagues, she lived to see her books become extremely popular. Yet Margarets success was not without its ambiguities. She remained acutely aware of having made her name in a sector of the literary world that most outside it did not take seriously. Extraordinarily accomplished writer that she was, she never freed herself altogether from the suspicion that to have written for adults would have been a greater achievement.

Its possible I knew some of Margaret Wise Browns books as a child growing up in the early fifties, but if I did I dont remember. This would not have surprised her at all. Of her own childhood memories of books, Margaret once remarked that it had not then occurred to her that books were written by people; what mattered was whether or not they rang true.

In any case, my work on the present book did not begin as a nostalgic quest for a favorite childhood author. As an undergraduate history major at Yale, I had become curious to know what kinds of books were published for young people during the early nineteenth century, when the American republic was itself still in its formative years. As I was also reading and writing a good deal of poetry, my interest in childrens literature naturally expanded to include the modern picture book, which at its best has much in common with lyric poetry: an ultimate clarity and compactness of expression, a seamless merging of matter and means.

I first became aware of Margaret Wise Browns work a few years after graduation, while browsing in a New York bookshop where copies of Goodnight Moon were stacked high on a table. As I read the book for the first time, unaware of the authors legendary status within her field (or indeed of anything about her) I was forcibly struck by the realization that the quietly compelling words I was saying over in my head were poetry and, what was more, poetry of a kind I prized: accessible but not predictable, emotional but purged of sentiment, vivid but so spare that every word felt necessary. Her words seemed to be rooted in the concrete but touched by an appreciation of the elusive, the paradoxical, the mysterious. There was astonishing tenderness and authority in the voice, and something mythic in it as well. It was as though the author had just now seen the world for the first time, and had chosen to honor it by taking its true measure in words.

I began looking for other books by her and discovered that there were lots of themover one hundred in all, more than forty of which remained in print over thirty years after publication. Although they varied in overall quality, several seemed memorable to me, many were very good, nearly all were in some sense innovative, and none was without a fresh perception or a jaunty phrase that stuck in the mind. (A train did not go chug chug but picketa-picketa, while another train went pocketa-pocketa; a dog could belong to himself.)

My curiosity was channeled into researchfirst for a critical essay and a magazine piece, then for this bookand as I proceeded to read the few articles that had been written about her and had my first conversations with people who had known her, I began hearing distinct echoes of the qualities I admired in Margarets writings. She was an original, more than one of her friends said. She was mercurial, quixotic, an experimenter, a perfectionist. Nearly everyone spoke of her in heartfelt superlatives, as an irreplaceable friend, as the most creative person they had ever known. In more than nine years of research and writing, I have been sustained by a core impression of Margaret Wise Brown as the least complacent of people, as a highly individual personality who time and again bravely tested her limits as a writer and human being.

Some of her experiments in literature and life, I learned, worked better than others. She was a poet of places, a master at shaping (decorating is not the word) her home surroundings into havens that mirrored the emotional warmth and whimsy, and the fascination with the primitive, of her imaginative writings.

However, she seems to have found it exceedingly difficult to meet her peers on equal terms, especially in love. As a lonely but delightfully resourceful child, she had at times to play parent to herself, and she learned the role well, though not without emotional cost, then and later. As an adult, she approached others obliquely, from above and below, with a beguiling mixture of childlike need and proprietary concern for the other persons welfare. She was forever enlisting collaborators, urging artists and writers to enter her new and largely unexplored field. A publishing colleague wondered, years after her death, if the picture book of all literary forms had not suited her so well precisely because it required the involvement of collaborators.

Over the years of the writing of this book, the first reaction of many people has been, How did she die? She died so young! I suppose this is natural given the fact that mention of her death in 1952, when she was still a young person (Margaret was forty-two), is just about the only biographical information supplied on the flap of Goodnight Moon, in the note that accompanies the photo of the attractive, open-faced author with a romantic glow.

Nonetheless, for a long time I was puzzled by the sheer intensity of peoples curiosity about this one question, and I have come to believe that it has at least two sources. The first of these is the Romantic myth of the creative artist whose genius flares brilliantly but briefly and is then snuffed out in tragic circumstances. The second is the common premise that childrens literature is a sentimental repository of innocent thoughts and happy endings, and little more than thathow ironic, then, when a childrens authors own story ends so