An imprint and registered trademark of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

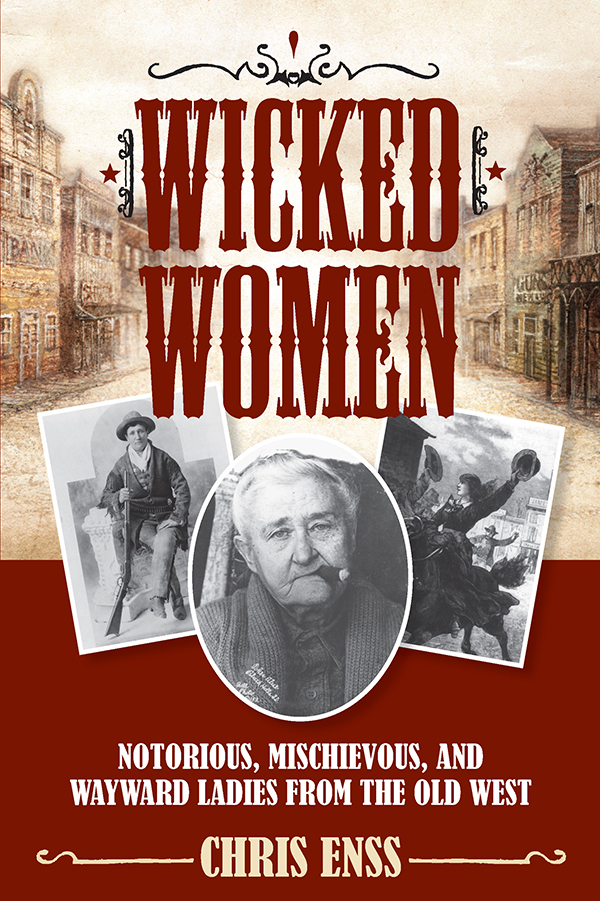

Copyright 2015 by Chris Enss

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including information and storage retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-0801-8 (paperback)

eISBN 978-1-4930-1392-0 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For Big Nose Kate, who gave as good as she got from Doc Holliday

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chasing down the history of the wicked women of Americas Old West has been a daunting but rewarding task. I have depended constantly upon the historians and photo archivists from Maine to Montana to complete this volume.

I am sincerely grateful to Chrystal Carpenter Burke at the Arizona Historical Society for going out of her way to provide me with some of the rarely seen pictures of the lady gamblers included in this volume. The Historical Society of New Mexico and the State Records Center and Archives department in Santa Fe were most helpful in supplying much of the information needed to write about Gertrudis Maria Barcel. The staff at the California History Room in Sacramento is always attentive and kind and makes visiting the library a true joy.

I appreciate the assistance of Jerry Bryant at the Adams Museum and House in Deadwood, South Dakota, and that of Matthew Reitzal at the South Dakota State Historical Society. Special thanks to Sara Keckeisen at the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka for generously giving her time and research talent as well.

The historians at the Nevada County Historical Library and Searls Library helped locate records on Eleanora Dumont and Texas Tommy. The staff members at each of the aforementioned locations were generous with their time and extremely patient. Their assistance is greatly appreciated.

Thanks most especially to my brilliant editor, Erin Turner. Im much obliged for all youve done over the years.

Introduction

The effect of vice upon the destiny of the expanding western frontier was considered by some religious and political leaders in the mid-1850s to be a sign of a rotten and decaying civilization. In 1856 Methodist pastor John M. Chivington told a congregation in Nebraska that the extravagant development of immorality, particularly the development of immoral women given to gambling, whiskey drinking and prostitution, marks the decadence of a potentially great nation. Ernest A. Bell, the secretary of the Illinois Vigilance Association, maintained that from the day the serpent lured the first woman in the garden there have been few days and nights when some daughter of Eves has not been deceived into a wicked life by some serpent or other. It has not changed and will not change.

In 1849 women of easy virtue found wicked lives west of the Mississippi when they followed fortune hunters seeking gold and land in an unsettled territory. Prostitutes and female gamblers hoped to capitalize on the vices of the intrepid pioneers.

According to records at the California State Historical Library, more than half of the working women in the West during the 1870s were prostitutes. At that time madamsthose women who owned, managed, and maintained brothelswere generally the only women out west who appeared to be in control of their own destinies. For that reason alone, the prospect of a career in the oldest profession must have seemed promisingat least at the outset.

Often referred to as sporting women and soiled doves, prostitutes generally ranged in age from seventeen to twenty-five, although girls as young as fourteen were sometimes hired. Women over twenty-eight years of age were generally considered too old to be prostitutes.

Rarely, if ever, did working women use their real names. To avoid trouble with the law as they traveled from town to town and to protect their true identities, many of these women adopted colorful new handles like Contrary Mary, Little Gold Dollar, Lazy Kate, and Honolulu Nell. The vicinities in which their businesses were located were also given distinctive names. Bordellos and parlor houses typically thrived in the part of a city known as the half world, the badlands, the tenderloin, the twilight zone, or the red-light district.

The term red-light district originated in Kansas. As a way of discouraging would-be intruders, brazen railroad workers around Dodge City began hanging their red brakemens lanterns outside their doors as a signal that they were in the company of a lady of the evening. The colorful custom was quickly adopted by many ladies and their madams.

Generally speaking, a prostitutes class was determined by her location and her clientele. High-priced prostitutes plied their trade in parlor houses. These immense, beautiful homes were well furnished and lavishly decorated. The women who worked at such posh houses were impeccably dressed, pampered by personal maids, and protected by the ambitious madams who managed the business. In general, parlor houses were very profitable. Madams kept repeat customers interested by importing women from France, Russia, England, and the East Coast of the United States. These ladies could earn more than $25 a night. The madams received a substantial portion of the proceeds, which were often used to improve the parlor house or to purchase similar houses.

The lifestyle was, without a doubt, a dangerous one, and many women despised being a part of the underworld profession. As Nebraska madam and prostitute Josie Washburn noted in 1896: We are there because we must have bread. The man is there because he must have pleasure; he has no other necessity for being there; true if we were not there the men would not come. But we are not permitted to be anywhere else.

Entertaining numerous men often resulted in assault, unwanted pregnancies, venereal disease, and even death. Some prostitutes escaped the hell of the trade by committing suicide. Some drank themselves to death; others overdosed on laudanum. Botched abortions, syphilis, and other diseases claimed many of their lives as well.

In the late 1860s a concern for the physical condition of prostitutesand moreover, for the effect their poor health was having on the community at largewas finally addressed. Government officials, alerted to the spread of infectious illnesses, decided to take action against women of ill repute. At a public meeting in New York City, a bill was introduced that aimed to curtail the activities of prostitutes who did not pass health exams. The goal of the bill was to stop the advance of what morally upright citizens termed the social evil.

A March 14, 1867, New York Times article reported on the proceedings:

The committee on public health today reported Mr. Jacobs bill for further suppression of prostitution. It was amended, at the suggestion of the author, by providing for the medical inspection of all females in registered houses and the detention of those diseased in a retreat under the control of the Board of Health.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.