ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At the end of seven years of intensive research and writing, its a pleasure to thank the people who helped me take this amazing journey.

Scott Mendel of Mendel Media believed in the importance of this story from the moment I sent him a short e-mail inquiry. Scott urged me to tell the human stories of the book smugglers, not only the history of the books, and thanks to him, the project took on a different shape and direction. Steve Hull of ForeEdge picked up where Scott left off and helped me grasp how narrative history differs from academic prose. It has been a pleasure working with him.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, which played a great part not only in the books story but also in my writing it. I was fortunate to have a quiet office at YIVO and to write this book in an atmosphere where the memory of Max Weinreich and Abraham Sutzkever is palpable. I did much intensive work during the semester when I was YIVOs Jacob Kronhill visiting professor. I want to extend special thanks to the library and archival staff who accommodated my every request and whim, even when it involved trips to YIVOs warehouse in New Jersey: Lyudmila Sholokhova, Fruma Mohrer, Gunnar Berg, Vital Zajka, and Rabbi Shmuel Klein.

YIVOs executive director Jonathan Brent not only encouraged me; he has dedicated himself to ensuring that the legacy of the paper brigade enduresby launching a monumental Vilna Collections Project, to digitize the books and documents in Vilnius and New York that are the subject of my book.

I benefitted from the assistance of institutions, researchers, librarians, and archivists in six countries.

At the outset of this project, I spent a very fruitful semester as a visiting scholar at the Leonid Nevzlin Research Center for Russian and East European Jewry, at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The Israeli archives were both a goldmine and a pleasant working environment. My special thanks to Rachel Misrati and the staff of the archives department of the National Library of Israel, and Daniela Ozacki of the Moreshet Archive in Givat Haviva. When I wasnt in Jerusalem myself, I could always count on Eliezer Niborski, editor of the Hebrew Universitys Index to Yiddish Periodicals, to track down articles in rare Yiddish newspapers. Despite my pestering, Eliezer never lost his good cheer and wry sense of humor.

A remarkable group of people supported and assisted my work in Lithuania. My friendship with the late Esfir Bramson, head of the Judaica section of the National Library of Lithuania, inspired me to write this book. As the custodian of the surviving portion of Jewish books and documents in Vilnius, she was a true heir to the tradition of Chaikl Lunski and the paper brigade. I regret that she didnt live to see this books publication. Her successor, Dr. Larisa Lempert, is a cherished friend who spared no effort to respond to queries and requests. Ruta Puisyte, assistant director of the Vilnius Yiddish Institute, was my devoted and wise research assistant, and Neringa Latvyte of the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum provided valuable information.

Vadim Altskan, senior archival projects director at the Mandel Center of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is a godsend to scholarship. Parts of the book smugglers story would have remained unknown to me were it not for his guidance and advice on locating archival resources.

Among the people who provided substantive feedback and saved me from embarrassing mistakes, I want to single out Avraham Novershtern, professor of Yiddish at the Hebrew University, who read and critiqued an earlier draft of the book manuscript. Greg Bradsher of the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, helped me swim in the waters of that mammoth repository. Bret Werb and Justin Cammy graciously shared with me their work and expertise on Shmerke Kaczerginski. Kalman Weiser shared documents from German and Polish archives on the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg looter and Judenforscher (Jewish expert) Herbert Gotthard.

Many scholars and colleagues contributed to this book with their comments and insights: Mordechai Altshuler, Valery Dymshits, Immanuel Etkes, Zvi Gitelman, Samuel Kassow, Dov-Ber Kerler, David G. Roskies, Ismar Schorsch, Nancy Sinkoff, Darius Staliunas, Jeffrey Veidlinger, and Arkadii Zeltser.

I am privileged to have known some of the heroes who participated in this story, and members of their families. Michael Menkin of Fort Lee, New Jersey, the last living member of the paper brigade, is my dear friend and a model of grace, generosity of spirit, and humility. He also explained to me things that I could never have known from any written source. I had illuminating conversations on the Vilna ghetto with Abraham Sutzkever in Tel Aviv in 1999. He remains a giant of literature and culture. Last but not least, Alexandra Wall trusted me with her notes, impressions, and memories about her grandmother Rachela Krinsky-Melezin. Alix is a devoted and proud bearer of the memory of her babushka, and of her mother, Sarah Wall.

I am fortunate to work in an institution that values what I do. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America has been my academic home and has helped form me as a scholar and person. Chancellor Arnold Eisen and provost Alan Cooper have supported this project and me from the outset.

My heartfelt thanks to the Biblioteca di Economia e Commercio, University of Modena, Italy, for hosting me in the summers and providing a quiet, pleasant space to write.

I am blessed with a loving family, who help me believe in myself: my mother, Gella Fishman, is, at age ninety-one, a powerhouse of energy and insight; my brothers Avi and Monele remind me gently about the importance of family commitments; and my adult children Ahron, Nesanel, Tzivia, and Jacob give me much pride and naches.

I owe my interest in Jewish Vilna, and therefore my writing this book, to two people who are no longer alive. First, my father, Joshua A. (Shikl) Fishman, who was a disciple of Max Weinreich and collaborated with him on many projects. Pa was the first person to tell me as a little boy about a magical place called Vilna and to instill in me a love for Yiddish. I mourn his passing and love him from afar. And second, the great Yiddish novelist Chaim Grade, with whom I developed a close friendship during the final years of his life. Thanks to Grades writings and conversations with me, prewar Vilna is as alive and vivid today as it was in 1930.

Words fail me in trying to express what I owe to my wife Elissa Bemporad. She has been my first and last reader, my learned critic and advisor. But beyond that, she has brought beauty, love, and poetry into my life. Together with her and our children Elia and Sonia, life is an exciting and joyous adventure.

AUTHORS NOTE

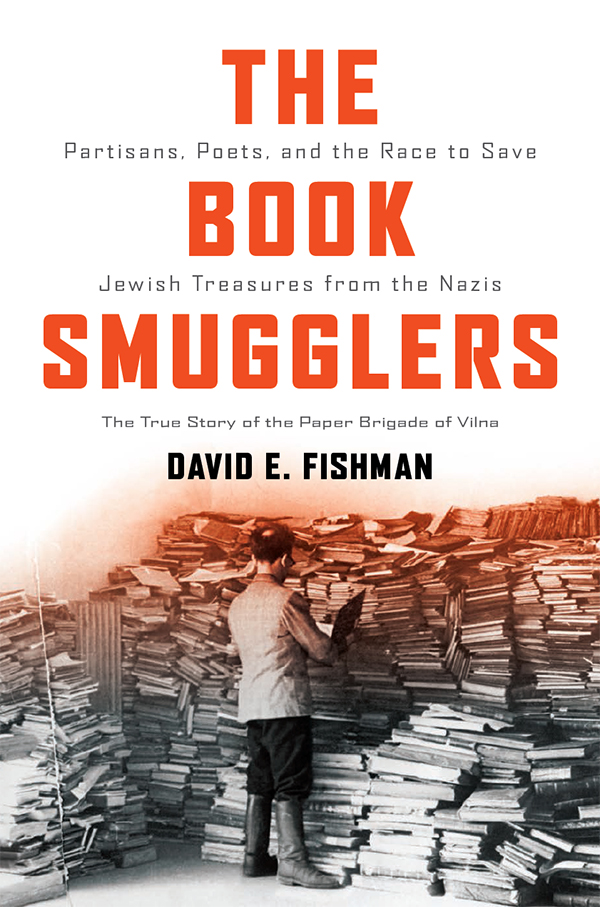

Most of us are aware of the Holocaust as the greatest genocide in history. Weve seen the images of concentration camps and piles of dead bodies. But few of us think of the Holocaust as an act of cultural plunder and destruction. The Nazis sought not only to murder the Jews but also to obliterate their culture. They sent millions of Jewish books, manuscripts, and works of art to incinerators and garbage dumps. And they transported hundreds of thousands of cultural treasures to specialized libraries and institutes in Germany, in order to study the race they hoped to exterminate.

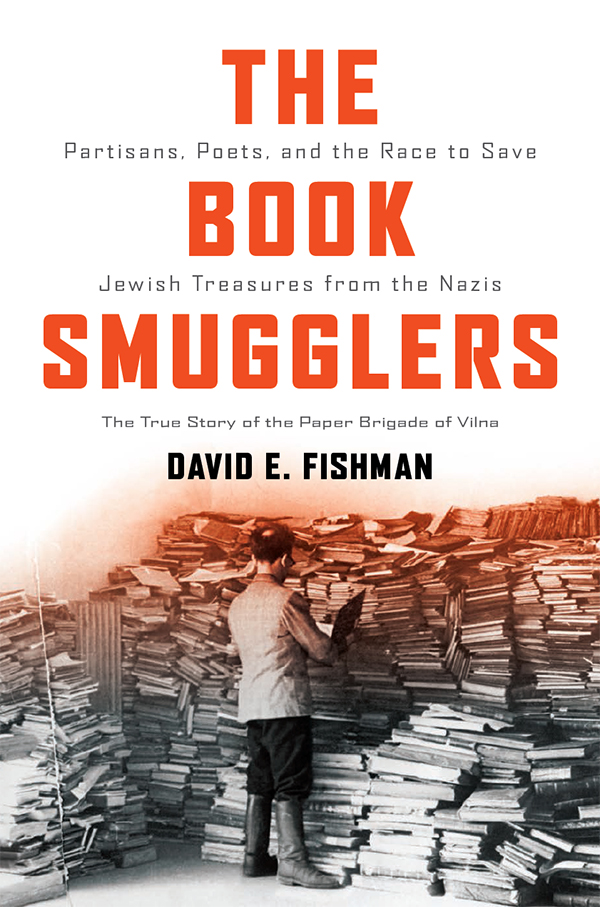

This book tells the story of a group of ghetto inmates that resisted, that would not let their culture be trampled upon and incinerated. It chronicles the dangerous operation carried out by poets turned partisans and scholars turned smugglers in Vilna, the Jerusalem of Lithuania. The rescuers were pitted against Dr. Johannes Pohl, a Nazi expert on the Jews, who was dispatched by the German looting agency Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg to organize the destruction and deportation of Vilnas great collections of Jewish books.

Next page