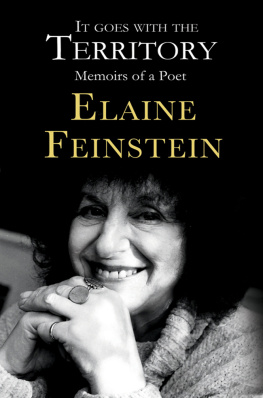

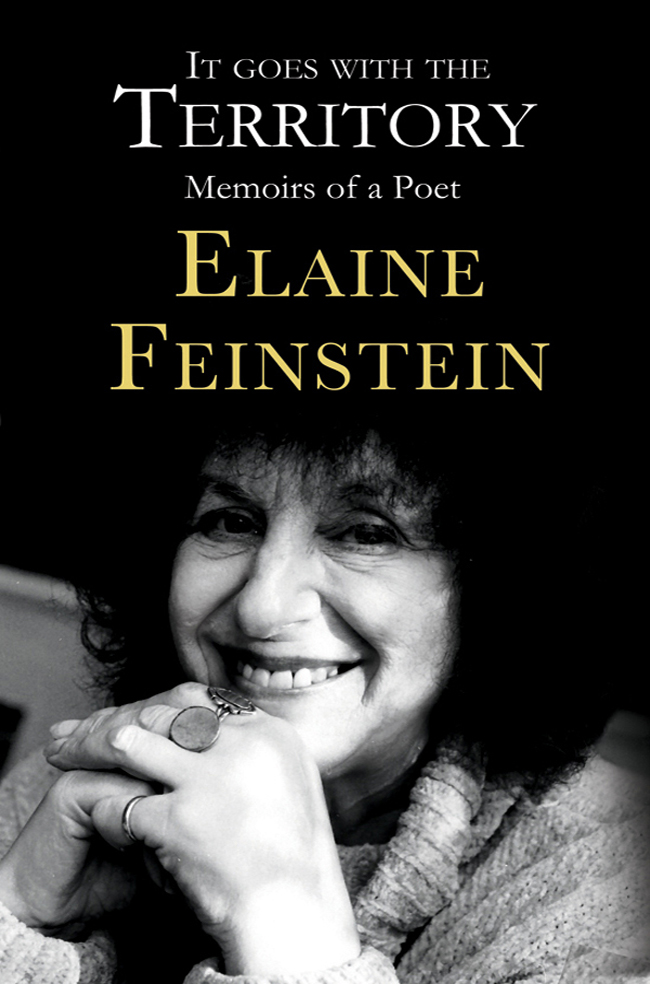

IT GOES WITH THE TERRITORY

IT GOES WITH

THE TERRITORY

Memoirs of a Poet

Elaine Feinstein

ALMA BOOKS

ALMA BOOKS LTD

London House

243253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almabooks.com

First published by Alma Books Limited in 2013

Copyright Elaine Feinstein, 2013

p. 67, lines from Wallace Stevens's Sunday Morning reproduced with kind permission from Pollinger Ltd. All rights reserved.

Photograph of Jill Neville Getty Images

Photograph of Fay Weldon Jonathan Dockar-Drysdale

Elaine Feinstein asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-84688-301-9

EBOOK ISBN : 978-1-84688-306-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

IT GOES WITH

THE TERRITORY

PRELUDE

Last week, I went to St Martin-in-the-Fields on Trafalgar Square and listened to a performance of Bach's Christmas Oratorio, directed by my son Martin. I came out buzzing with the tenderness and exhilaration of the music. It seemed to me, at that moment, that for all my eccentric dedication to a writing life, I have not too seriously harmed any of my three sons. Good fortune is unpredictable, but none of them will ever have to brood over what they failed to attempt.

I am not so sure about the damage done to my marriage. My desire to make poems and stories was as intense as any adultery, and the demand to put that ambition first is not readily forgiven in a woman. Still, poetry strengthened me in the face of more traditional infidelities and harsh words. And all our attempts to separate over fifty years came to nothing.

My childhood hardly equipped me for the life I wanted to find, but it was a happy one, and gave me an optimism I have never entirely lost. Jean Rhys once said that if she could live her life over again she would rather be happy than write. It is not a choice any of us are ever offered.

Elaine Feinstein, January 2013

CHAPTER 1

Foreign Roots

All four grandparents came from Odessa, a port on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine, and settled in the north of England some time in the last decade of the nineteenth century. They were all Jews, though the two families were remarkably disparate.

Dad's family loved the old rituals. I remember candles on Friday nights and crackly matzot on Passover. When my father told me the story of the Hebrews escaping from slavery in Egypt, it was as if he remembered the events himself. I must have been about four, and it was the most thrilling story I had ever heard. The following year I could read most of the English words in the Haggadah myself and found it something of a disappointment.

My mother's family, on the other hand, assimilated into English middle-class life in one generation. Two of her brothers went to Cambridge and learnt to speak a perfectly inflected standard English. None of them believed in God or his protection, and found my father's beliefs tiresome, though they were far too polite to say so.

As a child I gave the matter little thought, until one day in 1937 I was given a brusque awakening. I remember the smell of wet coats hanging up on the low hooks of the Cloakroom, so it was probably just after lunch. I had won one of the silver medals the Form Teacher awarded every week for good work. As I was pulling off my coat, with the medal proudly pinned to my tunic, a red-faced girl, whose name I can still remember but won't use, came up to me and sneered: My father says you are nothing but a dirty Jew. I was in floods of tears as I told my father after school, and I heard my parents talking about what action to take long after I had gone to bed.

Those were the years when Mosley's Fascists fomented riots among the unemployed in London and Manchester, though I don't remember my parents fearing violence in Leicester. What I did overhear, once I had begun to listen for it, was their alarm about what was happening in Germany. I remember my father refusing to buy me a balsa-wood aeroplane, powered marvellously by an elastic band, because it was made in a wicked country. He read the News Chronicle every morning and believed England had a quite different sense of fair play. The man I married many years later, however, saw another side of England. He grew up in Stepney, in Blackshirt territory, where he was taunted Go back to Palestine! and had his head banged against the paving stones of the schoolyard.

My own earliest memories are of a small house on Groby Road, Leicester a road which led to the outskirts of town, past the cemetery, towards a quarry where children were not allowed to play, although there were fascinating pebbles, some of which held fossils. Dad's father often came to stay with us in Groby Road after his wife died his children shared the care of him and I was told to call him Zaida. He was large and affectionate, with a ginger beard and deep laughter lines round his blue eyes. His yellow handkerchiefs smelled of snuff and the strong peppermints he carried in the pockets of a cardigan, which always sagged at the back. I liked to sit on his knee while he told me stories about the sunny streets of Odessa. He had been sent there to study after he lost the top joint of his first finger while minding a circular saw.

Zaida was always a dreamer. And he loved to study, particularly relishing heated argument over the meaning of rabbinic texts on a Saturday afternoon. He did not say much about his childhood in Belarus, or the hostility of their Ukrainian neighbours, though I remember he had wistful stories about young girls and boys playing hide-and-seek in the great forests.

He could read Russian, but he spoke Yiddish as a mother tongue. It was, I know now, a language used not only in the shtetls of the Pale but across the whole Jewish world from Russia through Germany to Paris, London and New York. It was a language rich in poems and stories. The poet Peretz Markish found it a genuine lingua franca, which brought him audiences wherever he travelled after the Russian Revolution. What took him back to Russia, fatally, was learning about the Soviet encouragement of Yiddish culture, especially Solomon Mikhoels's Yiddish theatre. Markish never wrote poetry in Russian, but Akhmatova herself translated him, and mentioned with delight his image of a dry leaf blown in the wind as scuttling like a brown mouse. Stalin had him shot on the Night of the Murdered Poets in 1952. These days, of course, as Isaac Bashevis Singer said when collecting his Nobel Prize, Yiddish is the language of ghosts.

The language was never spoken between my parents, but my father often used Yiddish phrases. For the most part they went along with a shrug. Not all of them find their place in Leo Rosten's remarkable book, The Joys of Yiddish, and friends in London who are more knowledgeable than I am in this area are puzzled by them. Perhaps they were local to Zaida's early days in Belarus, perhaps my father simply mispronounced the words.

If he was overtaken by a speedier car, he would say: