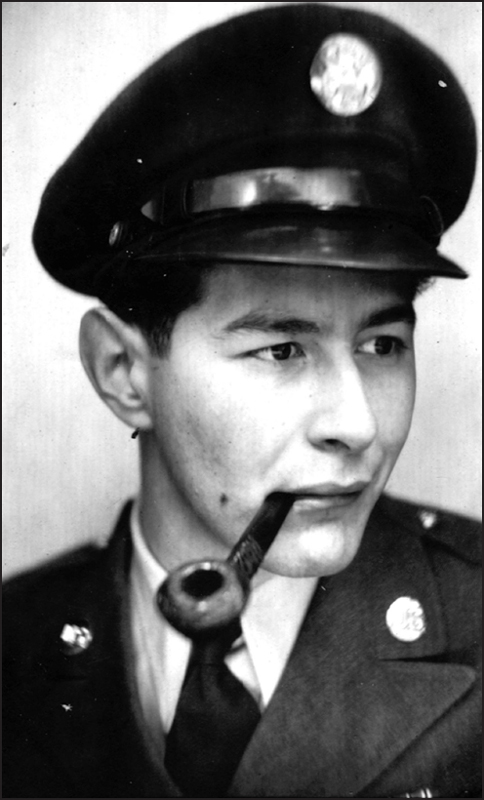

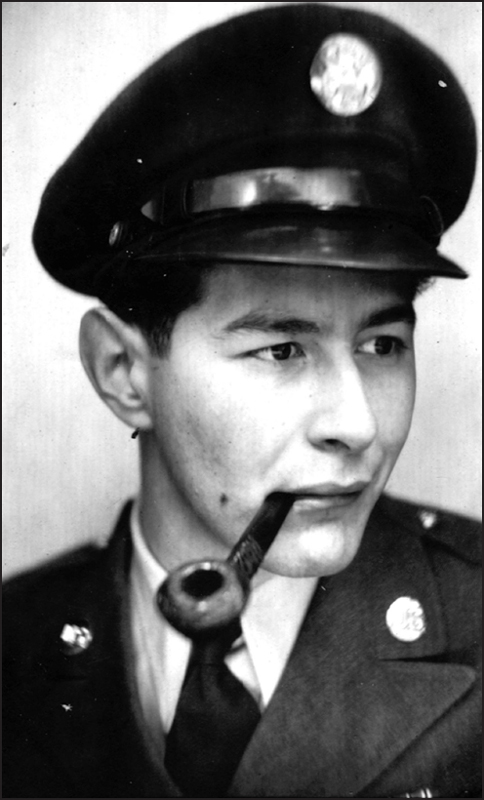

Walter C. Wolff in Paris, December 31, 1945.

Copyright 2014 by Nina Wolff Feld

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First Edition

The author wishes to thank Jeff King for his kind permission to reprint an extract from his blog.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

Visit the authors site at nwfeld.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Feld, Nina Wolff, author.

Someday you will understand: my fathers private World War II / Nina Wolff Feld.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-62872-377-9 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-62872-399-1 (ebook) 1. Wolff, Walter C. 2. JewsGermanyBiography. 3. Jews, GermanUnited StatesBiography. 4. Jewish refugeesUnited StatesBiography. 5. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)GermanyBiography. I. Title.

DS134.42.W68F45 2014

940.5318092dc23

[B]

2014016696

Cover design by Brian Peterson

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62872-399-1

Printed in the United States of America

For Jacob, so that Grandpa will always be in the room with you.

Contents

Part One:

Hidden in Plain Sight

Part Two:

The Long Road to Ritchie

Part Three:

Return from Exile

Authors Note

T his book is a work of nonfiction and is based in its entirety on the collection of letters written by my father to his family during his World War II service, which he saved for the rest of his life and entrusted to me not long before he died. All of the names of family, friends, soldiers, or Displaced Persons mentioned in this book come from those letters and in some cases from my own subsequent research for this book. The translation of the letters from their original French was done by me, and I have made every effort to be as accurate as possible. Any letters written in German or that have German writing in their letterhead were translated by scholars or friends. No historic work of this scope and nature can be free of error, but it is my hope that the reader will recognize the effort to achieve accuracy while trying to paint a full picture of my fathers experiences during his childhood and early manhood before, during, and in the early aftermath of World War II. All of the dialogue and gestures are drawn from the letters or in some cases from my fathers personal vernacular and body language as I knew him. All of the archival material, whether letters, postcards, Nazi propaganda material, or photographs, has been reproduced from my personal collection given to me by my father.

Preface

The Maginot Line of Memory

L ong before he was the man he would become, he was a boy running for his life. With a discriminating eye for detail and the inner mechanisms with which to cope, my father was lucky enough not only to survive but to remember moments with a certain fondness. Later, while he served in the US Army, he wrote with humor and dry wit in such vivid detail that a present-day reader of his letters feels as though immersed in a newsreel. Some of the persecuted from that time returned to prosecute. My father, Walter C. Wolff, was one of them. He sent war criminals to their fate.

Sometimes that which is precious shines through the misery of the continuum. As soon as there is an opportunity for normalcy, normalcy takes over so that recovery can begin. He almost never spoke to me about those years when I was growing up. Is silence needed to recover from the nightmares of war? Only gradually, and only after my father had died, did I begin to understand.

His elegant, cultured demeanor hid dark secrets of a childhood lost to time. He carried his memories like a lockbox for valuables. Occasionally, pieces were brought out, but his chosen memories were happy. They didnt reveal any of the terror his family had lived through, fleeing the onslaught brought about by Hitlers quest for world domination and ethnic cleansing. From conversations with my father, I had no idea what they had experienced; but if September 11 was one day of terror in my past, for him living that fear on a daily basis until safety was assured was certainly formative. When he reached me by phone from Italy on September 12, 2001, there was no disguise for his emotions or the significance of that date. I had only heard him cry like that once, when my grandmother died.

We were lucky that day; we lost a legacy but were very fortunate not to have lost any family or friends. The legacy was the Twin Towers. My father-in-law, Lester Feld, had been the chief structural engineer on the original Trade Center project. He went to Japan to inspect and select the type of steel used to build them. Since the towers were his lifes work, we always referred to them as Grandpa Lesters buildings when we pointed them out to our son. Lester died almost a decade before Jacob came into the world, and this was one way to give him a sense of who his paternal grandfather was. On the night of September 11, my then three-year-old son sat at his alphabet table in our old kitchen and wept over his strawberry Jell-O. He somehow understood that he would never see those buildings again and that the planned trip to visit them with his cousins on their next visit to New York would never come to pass. We had wanted to make it a special occasion, to make a day of it. The loss was devastating. War was at home. September 12 often recurred as a significant date in my fathers letters.

Silence is its own kind of mask. Yet, though silence and reserve were a constant while I knew my father, I grew up with a lot of love. I always felt thankful, for with that came the security to enjoy life and in turn return the love. Before he died, I even taught him to say, I love you, back to me. At the end, my fathers heart lost its strength, but I like to believe he used that muscle a lot in his life. It may have hardened to survive his childhood, but I knew it to be a soft and fiercely loyal muscle. He was a complicated man whose love was unconditional. I returned the favor. Even after their divorce, my parents could still find a way to love one another and never throw that to the wind. It meant everything to me. When he called me from Florence that day, he cried, How is your mother? It was for her that he opened his eyes one last time before dying, as she whispered into his ear that she loved him and always would. She kissed his feverish forehead before she said her last goodbye. Poetry.

I always felt the wonder of privilege. A great part of my education came from traveling.

When I look back to my childhood, I understand why we spent so much time in Europe. There was no need to discuss the past with the children; my father was too busy building a lifebusy with family and business. He had become a very successful furniture designer and retailer in New York after the war. He built his business around his lifestyle, and Bon March, his company, was the vehicle. All of the furniture was produced in European factories. We would travel back to what he had left behind because he found comfort in the familiarity. Yet, we never had a second home there. It would never be in the right place; it was too cumbersome and a weight. We had one home, where my mother still lives today. If there were any questions pertaining to his past, the answer was always, Someday you will understand.