Reprinted with the permission of The Baltimore Sun Media Group. All rights reserved.

I N THE MAIN BUILDING OF the CIAs sprawling Virginia campus, past the security guards and the detection machines, up a staircase and at the end of a winding corridor that doglegs to the left, is a windowless conference room. There is no name or number on the door. Inside, it has the feel of a space that might be used for a graduate seminar; theres a whiteboard on one wall and a table long enough to sit a dozen or so intelligence analysts. But there were only two other people seated at the table on the June day when I was therea distinguished agency historian and a press officer to watch over both of us. I had come with the hope of picking the scholars brain about Betty Pack, the British and American secret agent who had done so much to help the Allies win World War II.

It was, for me at least, a tense conversation. The CIA official knew, I suspected, a lot more than he was revealing, and I had the difficult task of trying to pull the information out of him. But he was a shrewd man who had spent a lifetime guarding secrets; he was not about to make an indiscreet revelation to me. Nevertheless, we both seemed to be enjoying the game until he took offense at something I had said.

I had announced that the book I intended to write would be a true story.

He laughed dismissively, and then launched into a lecture on the epistemology of espionage. Even nonfiction spy stories, to his way of thinking, were a search for ultimately elusive truths. The best that can be hoped for is a reliable hypothesis. No spy tale is ever the whole story; there are always too many unknowns, too many lies being passed off as facts, too many deliberate miscues by one participant or another.

I listened; argued meekly and defensively; and then did my best to move the conversation along to another hopefully more fruitful topic.

And now, having finished writing the nonfiction book that had prompted my visit to the CIA, I want to reiterate to its readers that this is a true story.

I have been able to draw on a treasure trove of information to tell Betty Packs story: her memoirs, tape-recorded reminiscences, childhood diaries, and a lifetime of letters; the Office of Strategic Services Papers at the National Archives; Federal Bureau of Investigation files; State Department records; the British Security Coordination official history; Foreign Office archives at the Public Record Office; and interviews with members of both the British and American intelligence services.

And yet I am also forced to acknowledge that there is a cautionary kernel of truth in the CIA scholars warning. There are, among the official sources, contradictory versions of events. And another caveatgovernments, even more than half a century later, hold on to their secrets. Bettys sixty-five-page FBI file is heavily redacted; tantalizing files at the National Archives are marked Security Classified information, withdrawn at the request of a foreign government; and the files assembled by H. Montgomery Hyde, Bettys wartime colleague in the British secret service and her first biographer, which were bequeathed to Churchill College, Cambridge, have been edited. Parts of this collection are closed indefinitely; individual documents have been removed by intelligence service weeders; and some papers have been officially closed until the year 2041.

Nevertheless, I reiterate: this is a true story. The narrative, a spy tale and a psychological detective story as well, is shaped by the facts I discovered. When there were two (or more) versions of an incident, I stuck with the one that made the most sense. When dialogue is in quotation marks, it has been directly quoted from a firsthand source. And when I share characters internal thoughtswhat theyre thinking or feelingthese insights are culled from their memoirs, diaries, or letters. A chapter-by-chapter sourcing follows at the end of this book.

H.B.

B ETTY P ACK HAD PLANNED HER escape from the castle with great care. Too often impulsiveher greatest fault, she would frequently concedeshe had deliberately plotted this operation with the long-dormant discipline acquired during her dangerous time decades ago in the field. Yet on the blustery morning of March 1, 1963, Betty, otherwise known in the tiny village in the French Pyrenees that lay just beyond the stone walls of the ancient castle as Mme Brousse, the American-born chatelaine of Castelnou, and who in a previous life had been known to an even smaller circle as the agent code-named Cynthia, was having doubts.

Betty had spent diligent months baiting the hook, then repeatedly recasting until it was firmly lodged, but now, just as the time had come to reel in her prey, she was suddenly anxious. She stood at the edge of the castles battlement as if on guard, a solitary figure, her gaze absently fixed on the pine forest in the distance, the raw wind charging in from the northwest with the savage shriek of an invading army. But Betty ignored the elements. The mighty windthe tramontane, as the awed locals called itwas nothing compared to the turmoil that must have been going through her mind.

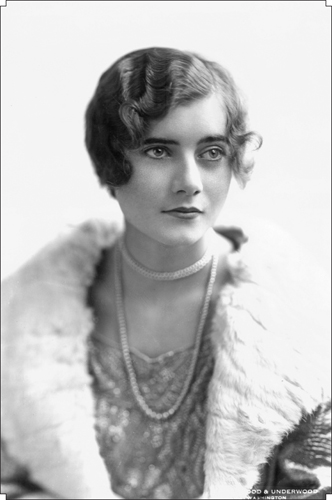

She was out of practice. She had lost her charm. At fifty-three, she was too old. Worse, she looked too old. It was a delusion, a pathetic, self-indulgent foolishness, to believe that a middle-aged woman could cast the same captivating spell that she had at twenty-nine. Her self-incriminating list went on and on, every charge in its way a pained reiteration of the same fundamental and unimpeachable truism: life, real life, always yields to age.

Then, all at once, Betty found the will. Was it simply a sharp burst of her old courage? A renewed realization that, as she had once written, happiness never comes from frustration? Or perhaps she told herself that too much had already been set in motion. There was no turning back.

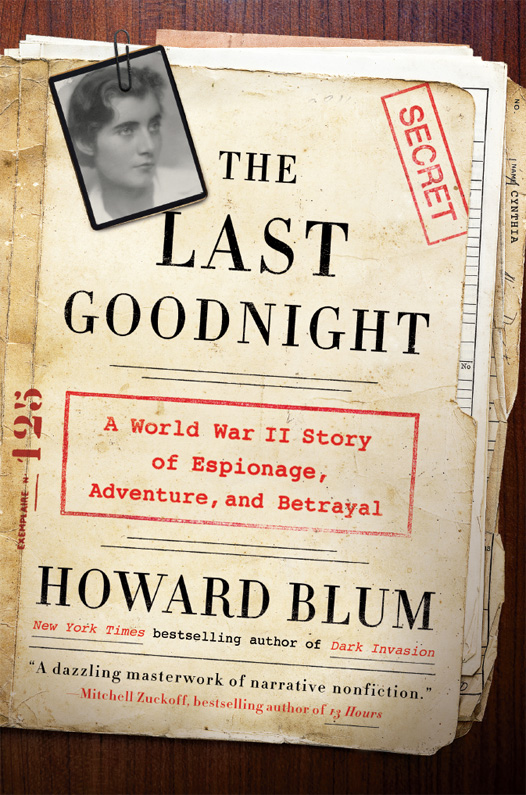

Betty, Charles, and their driver without their beloved Rolls.

Churchill Archives Center, Papers of Harford Montgomery Hyde, HYDE 02 007

Whatever the reasonor, just as likely, reasonsBetty, as she recalled the energized moment, was suddenly on the move. Without hesitation she made her way down the well-worn stone steps, strode in her long-legged, athletic way across the terrace, where the almond trees were already starting to bloom, and continued through the cobblestone courtyard to the waiting Rolls-Royce. The chauffeur was at the wheel. Her husband, Charles, was already in the back seat, his presence an inspired bit of cover, giving a pretense of legitimacy to the rendezvous that, if all went as she had so painstakingly designed, would soon happen.