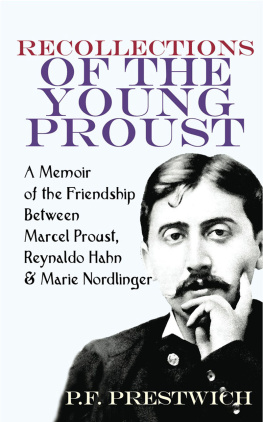

PRAISE FOR RECOLLECTIONS OF THE YOUNG PROUST

Although Prestwich pays equal tribute to each of her three protagonists, its undoubtedly the figure of Proust who keeps our interest afloat. Kirkus Associates, LP

It has a timeless fairytale quality The writing is zestful and broadly humorous, the philosophy that of a French D.H. Lawrence. Sunday Times

RECOLLECTIONS OF THE YOUNG PROUST

In 1896 Marie Nordlinger arrived in Paris to study painting. Her cousin, Reynaldo Hahn, was becoming known as a composer and his friend, Marcel Proust, was an aspiring novelist. P.F. Prestwich recounts the relationship between these young people. Drawing on letters exchanged between Proust, Hahn and Nordlinger who distinguished herself as an artist, journalist and businesswoman Prestwich weaves a portrayal of the fin-de-siecle European cultural elite. During the fourteen long years (18951909) he spent drafting preliminary episodes for his major novel, Prousts main passion and regular occupation was translating and interpreting John Ruskins works with Nordlingers assistance. Prestwichs analysis of the correspondence between Proust and his two friends helps offers a key to a fuller understanding of many episodes from In Search of Lost Time.

P.F. PRESTWICH was a freelance arts journalist, book reviewer and founder member of the British Association of Friends Museum. She worked with Marie Nordlinger for some years transcribing the correspondence between Marie, Marcel Proust and Reynaldo Hahn. She became a close friend of the Nordlinger family and the inheritor of Maries archive of letters and other memorabilia.

Contents

Illustrations

Unless otherwise indicatednext to illustration, all photographs are from P.F. Prestwich Collection

Introduction

This is the story of the friendship between three remarkable young people, an English girl who left Manchester College of Art in 1896 to continue her studies in Paris and two Frenchmen, her mothers cousin, Reynaldo Hahn, and his friend, Marcel Proust. Marie Nordlinger was twenty when she joined the life class at the Courtois studio in Neuilly; Hahn was twenty-two; he had left the Conservatoire de Musique and was already making his name as a composer and performer. His first opera was awaiting production. Proust, three years older, with degrees in law and philosophy, had just published his first book, a collection of short stories, poems and occasional pieces.

Marie was one of the first of Prousts circle of close friends to publish some of the letters he sent her; forty-one of them were included in Lettres une amie (Editions du Calame, Manchester, 1942), with an introduction in French by Marie giving a brief account of her collaboration with Marcel on the translation of two books by Ruskin, The Bible of Amiens and Sesame and Lilies. Of the letters which she kept and published, over half date from 1904, the year when they were correcting the proofs of La Bible dAmiens and translating the lecture on reading from Sesame and Lilies. She was the only woman, apart from his mother, to be actively concerned with his work, and she published his letters in the hope that they would bring more English readers to his novel and also to show how the discipline and dedication at this stage of his career was carried over to the writing of A la recherche du temps perdu. There are only a few casual references to Ruskin in the novel, but his influence on Prousts development as an artist was profound.

Their shared enthusiasm for the fine arts, cathedrals, the countryside and Ruskin drew Marie and Marcel together, but the mainspring of their friendship was their tacit devotion to Reynaldo Hahn they were both in love with him. His good looks, elegant manners, his charisma as performer and speaker exerted a strong attraction over both women and men. Although he had been born in Caracas, and is still often referred to as Venezuelan, he was a Parisian through and through the family made Paris their home when he was three. He had a French verve and wit combined with Spanish pride and melancholy. He soon came to appreciate his Manchester cousins character and capabilities, treating her as a younger sister to be encouraged, teased, educated and advised. With Marcel he shared a passion for reading, an eager curiosity and a love of music (in Reynaldos case particularly a love of singing); he was as talented a writer as he was a composer. He learnt as much about literature from Marcel as Marcel learnt from him about music, which plays an important role in A la recherche du temps perdu. The letters he received from Marcel are quite different from those to any of Prousts other correspondents and show how close their relationship was for nearly thirty years, ending only with Marcels death. So, too, the friendship between Reynaldo and Marie, though interrupted by two world wars, lasted until Reynaldo died in 1947.

During the exhibition of Proust manuscripts and memorabilia held at the Wildenstein Gallery in Bond Street in the autumn of 1955, there was an essay by Marie on Proust and Ruskin in the catalogue. The following year, when she was eighty, she organized an exhibition of her own at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, with the support of Professor Eugne Vinaver, then head of the French Department at the university and French cultural delegate in the north of England. He asked me to help her with the catalogue and we became friends in spite of the difference in age. To please her daughter and other friends she began, reluctantly, to draft her memoirs, but it was apparent that she felt she had said all she had to say about Marcel and it was now Reynaldo she wished to commemorate. When she died in 1961, the memoirs ended in 1905 after her first visit to America.

During the years we worked together transcribing her letters from Reynaldo and those he wrote to his sister, Maria de Madrazo, she often told me about her family; her conversation was not all reminiscence, fascinating as her memories were. Certainly she was a woman of her era, an Edwardian; her views were well in advance of many of her contemporaries, but by upbringing and temperament she did not care to talk about herself. Not one of us among the family and close friends had the least suspicion about the depth of her feelings for Reynaldo. There were questions I did not think to ask, or did not care to press. And she never gave me a satisfactory answer to one question I asked more than once: What made Marcel so enthusiastic about Ruskin?

She had always hoped to publish an English edition of her letters from Proust, but never did so. Both she and Reynaldo planned to make a selection of the letters Marcel wrote to him, which Reynaldo described as high-spirited nonsense, full of jokes which amused us but were incomprehensible to anyone else. They are quite With this shorter memoir, The Translation of Memories, we hope to add a new dimension to the friendship between these three young people in the early years of the twentieth century and especially Prousts debt to Ruskin and the part played by Reynaldo in the development of A la recherche du temps perdu.

Many potential readers of Prousts novel are deterred by its length. The three volumes of the revised translation by Terence Kilmartin and D.J. Enright contain over 3,000 pages (there is a more convenient paperback version in six volumes). Some readers never get further than Swanns Way, the first of its seven sections, discouraged by the absence of paragraphs and the long, involved sentences. Marie always maintained that no one should try to read all the volumes straight through but should dip into them and return to them at leisure.