Published by Stackpole Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

800-462-6420

Copyright 2019 by James H. Hallas

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-0-8117-3843-9 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8117-6843-6 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

BY EARLY 1944, IT HAD BECOME CLEAR THAT JAPAN WAS LOSING THE WAR. As the United States brought its immense military and industrial power to bear, the seemingly invincible Japanese juggernaut had sputtered and begun to recoil under a succession of defeats. Though the Japanese public remained largely oblivious, high-ranking military officers and knowledgeable government officialseven the emperor himselfwere all too aware of the decline in Imperial fortunes. Victory, once seemingly so close at hand, had begun to slip inexorably away.

In response, Japanese military and political leaders decided to bet the fate of their nation on a calculated roll of the dice. Carefully husbanding its resources, the Imperial Navy would wait until the moment was right, then sally forth for a decisive confrontation with the U.S. fleet. The powerful force of carriers, battleships, and land-based aircraft would then inflict a defeat of such magnitude on the American devils that their stunned enemy would agree to a negotiated peace.

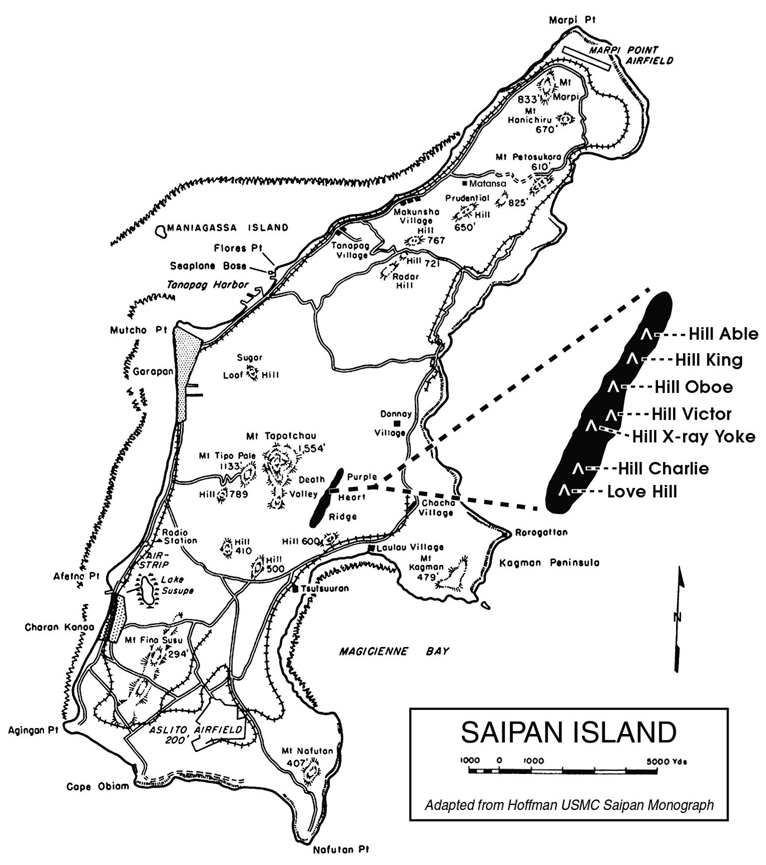

The much-awaited opportunity arrived in mid-June 1944 when U.S. forces began to land on the island of Saipan in the southern Marianas. While Japanese soldiers mounted a tenacious defense on the ground, a powerful naval force set out to destroy the U.S. Fifth Fleet. The ensuing sea battle took place over two days, while the ground fighting on Saipan dragged on into July. When it was all over, Japanese hopes for victory lay entombed with thousands of navy pilots and seamen beneath the waves of the Philippine Sea and other thousands of Imperial infantrymen moldering among the burned cane fields and rugged hinterlands of once tranquil Saipan.

It may seem presumptuous, given the nature of the war in the Pacific, to single out any one action as the battle that doomed Japan. Victory in the Pacific was cumulative, marked by any number of turning points or milestones such as the Coral Sea, Midway, and Guadalcanal in the long march toward peace. The American victory at Saipan did not end hostilities. Peleliu, the Philippines, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and a host of other bloodbaths, large and small, still lay ahead, claiming the lives of many more thousands of Americans and Japanese. But it was the defeat of the Imperial Navy in the waters off Saipan in June 1944 and the fall of the island itself in July that emphatically demonstrated to the Japanese that the war was lost.

The ramifications of the confrontation at Saipanto include the naval battle of the Philippine Seawere both varied and far-reaching. The inexorable American advance had shattered the much-vaunted Absolute Defense Sphere, brushing aside a Japanese navy that had once seemed virtually invincible and eradicating Japanese naval airpower as a significant threat to U.S. operations in the Pacific. The emperor himself began to press his advisors to search for an honorable exit from the war that had begun so auspiciously and now, only two and a half years later, threatened his nation with destruction.

The disaster forced the resignation of prime minister Gen. Hideki Tojo, whose Cabinet had led Japan since late 1941, and encouraged a nascent peace movement in some of the highest military and government circles. To the man in the street, the loss of the supposedly impregnable island bastionhome to a substantial Japanese civilian populationwas incontrovertible proof that the Americans were closing in on the homeland. That proof would soon be clearly visible overhead. American air bases on Saipan, Guam, and Tinian brought the Japanese home islands within range of the newly developed B-29 Superfortress bombers, which would proceed to lay waste to city after city in a firestorm that would culminate in mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Events at Saipan were also to have a more subtlebut no less significantimpact as they helped shape American and Japanese thinking and decision-making over the next thirteen months. Higher than anticipated American casualties in the ground battle for the island left planners brooding over potential losses in any invasion of the Japanese home islands. The so-called Saipan ratio suggested that U.S. casualties would be enormous500,000 at a minimum and quite probably higher. Those concerns were not eased by the highly publicized suicides of what were said to be thousands of Japanese civilians on Saipan as defeat loomed. If even the civilian population on Saipan embraced an orgy of self-annihilation, what would happen when American forces invaded Japan with its many millions, each man, woman, and child a potential enemy?

Saipan also gave rise to two controversies that linger to this day. Historians continue to debate Adm. Raymond Spruances handling of the Fifth Fleet during the battle of the Philippine Sea. Though his carrier pilots won a stunning victory, Spruance was criticized for what many perceived as a lack of aggressivenessa failure that may have cost him the opportunity to destroy the Imperial Navy in one fell swoop. Meanwhile, the ground campaign for Saipan spawned one of the most toxic interservice controversies of World War II when Marine lieutenant general Holland Smith relieved U.S. Army major general Ralph Smith of command of the 27th Division. The disparaging allegations involving Ralph Smith and the 27th Divisions performance on Saipan and the counterclaims against Holland Smith and their potential effect on interservice cooperation reached such proportions that it threatened to hinder the prosecution of the war in the Pacific.

Ironically, considering its significance, Saipan has been called the bloodiest battle you never heard of. Overshadowed by the Allied landings in Normandy the week before, the campaign has only recently been explored in any detail by historians writing for a more general audience. That recognition is long overdue. As a simple matter of logistics, the execution of the operation, simultaneously with the Normandy landings half a world away, was an unparalleled show of American military and industrial might as well as a stunning demonstration of the evolution of the amphibious assault and the lethal reach of naval task forces built around the new queen of the seas: the aircraft carrier. The D-Day landings on the coast of France were conducted over 20 miles of water separating England from the Continent. The assault on Saipan moved 535 ships and over 70,000 men some 3,200 nautical miles across the vast Pacific to land on a hostile shore only 1,250 nautical miles from Tokyo.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.