Campaign 137

Saipan & Tinian 1944

Piercing the Japanese Empire

Gordon L Rottman Illustrated by Howard Gerrard

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

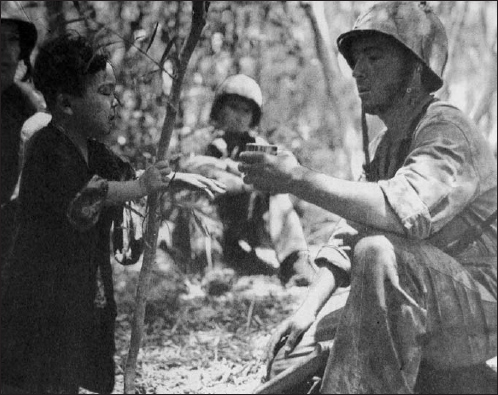

The northern portion of Charan Kanoa, Saipans second largest town, lies in ruins after the battle; the rubble has been cleared from the streets. In the upper right portion can be seen the steel smoke stack of the sugar refinery. A Japanese artillery observer spotted from there until he was discovered days into the fighting. The spit of land to the left of the refinery is the boat dock.

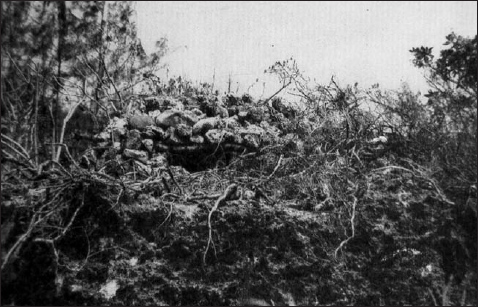

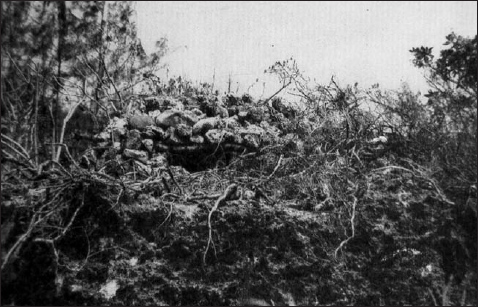

While Saipans coast defense guns were mounted in concrete casemates, most of the infantry defenses were crude owing to limited time and materials. This thatch-covered section of trench offered protection only from the sun and rain.

INTRODUCTION

B y the summer of 1944 the Allied counteroffensive in the Pacific was in full swing. The Solomon and Bismarck Islands in the South Pacific had long been secured, as had eastern New Guinea by General Douglas MacArthurs Southwest Pacific forces. In the Central Pacific, the Gilbert Islands had been cleared the previous year and the Marshalls had been seized. Some bypassed Japanese garrisons remained in these areas, but they were slowly being bombed and starved into submission and posed no threat. The great Japanese naval and air bases at Rabaul on New Britain and Truk in the Marshalls had been neutralized, giving the US Third and Fifth Fleets free rein in the Central Pacific. In September 1943, the Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) established Japans outer defense line running from the Dutch East Indies, through eastern New Guinea, the Carolines, Marshalls, and Marianas. However, the thrust into the Marshalls had already penetrated this line. Beginning in AprilMay 1944 the Allies conducted several landings on the north coast of New Guinea. In the Central Pacific, the Marianas would be the next Allied objective.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

Long-range planning for the Pacific War was directed through a series of high-level conferences between the US president, the British prime minister, occasionally other heads of state, and the chiefs of staff of the combined armed forces. The January 1943 Casablanca Conference, while establishing basic objectives for the war in the Pacific, did not include the Mariana Islands among them. The same applied to the May Trident Conference. Objectives in the Central Pacific were expanded, but still the Marianas were not specifically included. At both conferences the Navy had argued the importance of seizing the Marianas making full use of its growing fleets, both for liberating the Philippines and for the invasion of Japan, but this was ignored. At the same time General MacArthur remained totally focused on this Southwest Pacific drive with the objective of seizing the Philippines via New Guinea. He opposed a major thrust through the Central Pacific fearing that it would siphon resources from his efforts. Ironically, it would be one of the Navys strongest opponents that ultimately urged that the road to Tokyo should be driven through the Central Pacific. The Air Forces new long-range bomber, the B-29, was now being deployed. The only operating bases within range of Japan were in China. This forced the Superfortresses to fly to their maximum range and still allowed them to reach targets in only parts of Japan. The logistics of transporting ordnance, fuel, spare parts, and all the other necessary supplies into China from India was a major difficulty. The Air Force pointed out that airbases in the Marianas would place Japan within the bombers range and could be easily supplied by ships direct from the United States. With the Navy and Air Force joining forces at the December 1943 Cairo Conference (Sextant), they successfully argued that a two-prong attack through the Central Pacific and the Philippines would more effectively achieve the defeat of Japan. This would secure objectives from which they could conduct intensive air bombardment and establish a sea and air blockade against Japan, and from which an invasion of Japan proper could be launched if necessary. The Central Pacific Operation Plan, Granite II, was completed on 27 December 1943 with a tentative date for seizing Saipan, Tinian, and Guam of 15 November 1944.

This machine-gun position was constructed of limestone rocks, blended into the surrounding terrain, and well camouflaged with brush. Most of the flamethrower-scorched brush had been pulled away to reveal the position. Such positions were well camouflaged and too small for naval gunfire spotters to detect and had to be reduced by infantrymen.

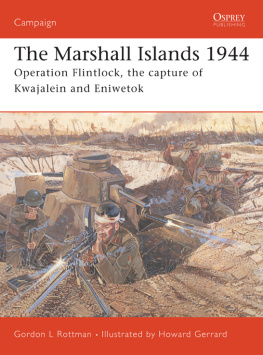

In war, plans change once a campaign is under way and Granite was no exception. It was kicked off exactly on schedule with the 31 January 1944 assault on Kwajalein in the Marshalls. The speedy success of this operation freed reserves to seize Eniwetok two months early, in February rather than May. At the same time MacArthur again attempted to sell his plan and even convinced some on Admiral Chester Nimitzs Pacific Fleet staff that the New Guinea and Philippine route was more favorable and that a drive through the Central Pacific was unnecessary. When presented to Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, he chastised Nimitz for failing to stay the course. The Marianas assault was moved forward two weeks. In mid-February the formidable Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) bastion at Truk in the central Marshalls, the Gibraltar of the Pacific, was neutralized by sea and air. This suddenly opened the way to the Marianas. MacArthur too was able to step up his operations and quickly seized the Admiralty Islands at the end of February. The Washington Planning Conference in February and March 1944 set the schedule for the remainder of the Pacific War. Of the six phases identified by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, number 4 was, Establishment of control of the MarianasCarolinesPalau area by Nimitzs forces by neutralizing Truk; by occupying the southern Marianas, target date 15 June 1944; and by occupying the Palaus, target date 15 September 1944.

Seizing only Guam would have both satisfied the political need to expunge the US defeat in 1941 and provided a base for the airfields from which to bomb Japan. Saipan and Tinian could have been neutralized by naval and air power. However, it was thought better to destroy the significant enemy forces on these islands and to develop airbases on the more favorable terrain. In addition Saipan and Tinian were 100 miles (161km) closer to Japan than Guam.

To support operational planning, up-to-date intelligence was required. Navy aircraft took the first aerial photos of Saipan and Tinian in February, but clouds prevented full coverage. Additional missions in April filled the gaps. Photo update missions were flown in May. In April a submarine photographed the shorelines of both islands, but no reconnaissance teams attempted to infiltrate the island.

THE MARIANA ISLANDS

The Mariana Islands chain (Gateway) is known to the Japanese as Mariana Shoto. The Marianas 15 islands run north to south in a shallow curving chain 425 miles (684km) long, some 300 miles (483km) due north of the West Caroline Islands. Pearl Harbor is 3,400 miles (5,471km) to the east, Tokyo 1,260 miles (2,028km) to the north-northwest, and Manila 1,500 miles (2,414km) to the west. Some 500 miles (805km) to the northwest is Iwo Jima, the next stepping-stone to Tokyo.

Next page