Copyright 2014 by David Halton

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives of Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Halton, David (News correspondent), author

Dispatches from the front : the life of Matthew Halton,

Canadas voice at war / David Halton.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-7710-3813-6 (bound).ISBN 978-0-7710-3821-1 (html)

1. Halton, M. H. (Matthew Henry), 1904-1956. 2. JournalistsCanadaBiography. 3. War correspondentsCanadaBiography.

4. World War, 1939-1945JournalistsBiography. 5. World War, 1939-1945Press coverageCanada. I. Title.

PN 4913. H 348 H 34 2014 070.4333092 C 2014-904636-7

C 2014-904637-5

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by

McClelland & Stewart, a division of Random House of Canada Limited

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013938806

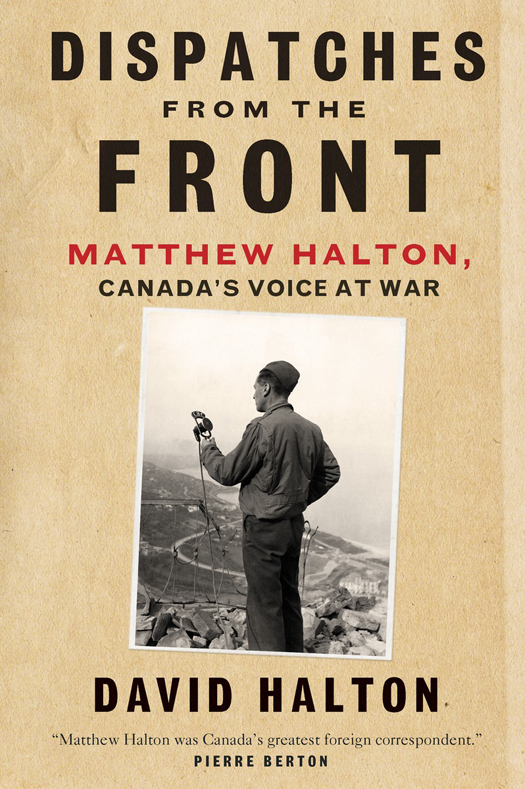

Cover photograph: Matthew Halton, CBC Senior War Correspondent, records his impressions. He is standing on a hill overlooking Ortona the scene of a great Canadian exploit in this war (WWII). An artillery barrage was in progress when this picture was taken. CBC Photo, A037546.

Designed by Leah Springate

McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited,

a Penguin Random House Company

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For Matt and Jean

CONTENTS

PREFACE

O N AN EARLY SPRING DAY IN 1987 , Zilla Soriano, a student of journalism at Ryerson Polytechnic Institute in Toronto, made her way into the archives of CBC Radio in an old mansion on Jarvis Street. Her professor had assigned her to a research project on Matthew Halton, a World War Two broadcaster whose name until then was as unknown to her as it was to most of her classmates. Closeting herself in a tiny audio booth in the archives, she began listening to dozens of his tapes piled in front of her. The first was an eyewitness account of entering Berlin on VE Day, May 8, 1945. Four out of five buildings had been destroyed that is, completely leveled or completely gutted. This did look like the end of the world. Through the rubble and ashes of Berlin I didnt recognize famous streets I had known well. We were lost for a few minutes in that utter ruin and silence. I was afraid.

Soriano later wrote that it was the voice that got to her first. It was clear, unhurried, conveying a sense of both urgency and authority. Suddenly I am no longer sitting in that safe little cubicle at the CBC listening to old tapes. Instead I am moving with Matthew Halton into the still-smoking and burning city of five million people. His fear becomes my fear, his pain mine. The voice hypnotizes and the script it is more like an essay mesmerizes.

It was the same voice, as she would discover, that had a riveting impact on a generation of Canadians. For me, it was simply my fathers voice not much more than a passing curiosity for a five-year-old boy at wars end. For millions of people, though, it was the voice of Canada at war more familiar on the home front than that of any of the countrys politicians or

The Ryerson student soon made other discoveries about Matthew Halton. Her initial fears that she had been assigned to study an obscure figure from the past quickly disappeared as she learned that she was dealing with a celebrity in his time. Seven years after his death in 1956, at the age of fifty-two, Matt was still being hailed as without question Canadas greatest foreign correspondent, both as a writer for the Toronto Star and, after 1943, as a reporter for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The son of struggling English homesteaders in rural Alberta, he was to embark on a remarkable journalistic odyssey through the turbulent first half of the twentieth century. It was a journey that put him on the front lines of many of the major political and military events of the era. He was in Berlin on the day Hitler took full power in Germany and long before most other correspondents began a prophetic series of reports warning that the Third Reich was becoming a vast laboratory and breeding ground for war. For the rest of the decade he chronicled Europes drift to disaster, covering the breakdown of the League of Nations, the Spanish Civil War, the sellout to Fascism at Munich, and the Nazi takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia. Along the way he interviewed Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hermann Gring, Neville Chamberlain, Charles de Gaulle, Mahatma Gandhi, and dozens of others who shaped the history of the century.

It was a career that brought him international acclaim of which few journalists can even dream. Matts wartime broadcasts for the CBC were regularly used on the BBC ; his dispatches from the front were widely published by British newspapers as well as by the Toronto Daily Star and Macleans. In 1944 the Association of British Publishers named him one of the five best war correspondents of World War Two. He won one of the most prestigious broadcasting prizes in the United States and was admitted to the Canadian News Hall of Fame. King George VI awarded him the Order of the British Empire.

Today though, more than five decades after his death, Matthew Henry Halton is a more or less forgotten name for all but survivors of the wartime generation. Apart from an admirable History Channel documentary about him and a small exhibit in the Canadian War Museum, there are few reminders of an epic journalistic career. Ask students in journalism classes across the country about Matthew Halton and the response will almost inevitably elicit the same blank stares as those of the Ryerson student and her classmates when they first heard his name. Unlike the famous American broadcaster Edward R. Murrow, to whom Matt was often compared, there are no journalism foundations named after him, no plaques, no awards and scholarships in his name, and barely more than a footnote about him in journalism textbooks.

This biography hopes to re-awaken interest in a Canadian legend. For more than four years, I have tracked down and interviewed my fathers few surviving colleagues. I have prodded aging relatives for memories and insights. I have followed his path from the birthplace he cherished in rural Alberta to the universities he attended in Edmonton and London, and then to many of the memorable places and battlefields that marked his career. I have spent eighteen months in the national archives reading virtually all of the estimated four million words he wrote for newspapers and radio. I have sifted through his diaries and the large collection of letters he wrote to his friends and family. The sources, many and rich, have drawn me into an absorbing and at times obsessive search for the details of one mans life.

My admiration for my father will be evident at times in this biography. He was, after all, the inspiration for my own decision to become a journalist. But the reader should be assured that this is not a hagiography. I have made a determined effort to assess Matts flaws both as a reporter and as a human being. I have tried to unravel the many paradoxes and contradictions of his life: the writer who could summon searing, majestic language yet lapse on occasion into purple prose; the fervent Anglophile who detested the British class system; the socialist who befriended millionaires; the war correspondent who loathed bloodshed yet became addicted to the thrill of battle; the loner who thrived in good company; the aspiring but failed poet; and, in some ways most puzzling of all, the womanizer with a deep and abiding love for his wife. This book, I hope, will throw light on some of those contradictions and on one of the most accomplished journalists of his time.