Contents

Guide

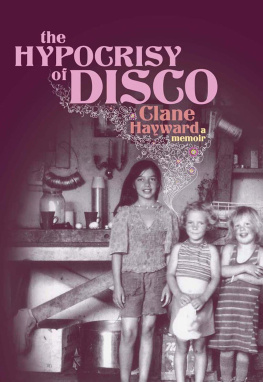

To Disco, with Love

The Records That Defined an Era

David Hamsley

FLATIRON

BOOKS

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In 2001, I went to an exhibit of record album art at a gallery in New York City. The walls were papered from floor to ceiling with covers of every description. The crowd was enthralled, pointing at familiar pop stars, reminiscing about where they were when they first heard a certain song, or connecting again with an album that seemed to never stop spinning all through college. I wondered what it was about a twelve-by-twelve-inch album cover that could engage just about anybody. The curators of the show were people like meso dedicated to records its almost as if free will didnt count. I envied their ability to express their devotion and dreamed about what I could do to celebrate album art. As my wheels turned, I realized that conspicuous by its absence was any spotlight on the Disco eraa particular favorite of mineand I decided at that moment that I had a mission, a calling, to change that. To Disco, with Love is the result.

I thought I knew all about the history of Disco because I had lived and loved it. But as I started to research, I realized what I knew was far from the whole story. Studying the Disco Action charts found in scratchy, microfilmed issues of Billboard magazine at Lincoln Centers library was an eye-opener. The first Disco chart appeared in November 1974, with record positions calculated by audience response as reported by a few New York DJs, and by sales reported by select New York record shops that specialized in this new music. It was barely enough to fill two skinny columns. But by September 1976, a little less than two years later, the magazine was devoting an entire page to what was being played in fifteen major cities across the country. Billboard magazine, the music industry bible, was telling the country that Disco had arrived. Each city, unsurprisingly, had its own personality. As Detroit was defined by Motown and its particular sound, Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, grew to be defined by its unique Disco sound, one that was characterized by a smooth orchestral Soul. Miami also had its own sound, exemplified by KC and the Sunshine Bands catchy beats, breezy hooks, and tempered by the endless summer and miles of beaches. And Los Angeles often danced to a song that wasnt being played in any other city. (It should come as no shock that David Bowies Fame made Disco playlists there and nowhere else.) By September 1979, there were so many tracks that Disco had its own National Top 100.

Going over these charts with a fine-tooth comb felt like I was reading the diary of an old friend and learning something new about him on every page. Each time I came across an unfamiliar song, I wrote it down and went hunting. In the end, I collected over 1,600 albums. Through this project, I came as close to going back as one possibly can.

By the time I finished writing, one thing was abundantly clear: Discos soundscape was richly textured and open to a myriad of influences, not the homogeneous, it-all-sounds-the-same blur some people remember it to be. It is important to note that in the early days an album could have a track that got the attention of the dancing public, but not be a Disco album, per se. Papa John Creach played fiddle with Jefferson Airplane, and Buddy Miles played drums behind Rock legend Jimi Hendrix. Both had albums that contained floor-filling cuts, but they were definitely not Disco albums. In the same way, Jazz also enjoyed a good share of floor time. In the spring of 1975, four of the biggest Disco hits were by Jazz artists: the Brecker Brothers, Hubert Laws, Ramsey Lewis, and Grover Washington Jr. Latin music also exerted a huge influence over Discos sound, and although authentic acts like Louie Ramirez, Jos Fajardo, and Fania All-Stars were quickly washed off playlists by the flood of releases, the echoes of Salsa, Mambo, and Cha-Cha can be heard in many Disco arrangements. Later, when time and tide were right, Disco dancers warmly welcomed the B-52s New Wave and Kurtis Blows Rap. All that ever really mattered was that the song made a dancer want to dip, spin, and bump.

The disco itself became a social stage upon which the fantasies and excesses of the later 1970s played themselves out. Much, almost too much, has been made about the role the sexual revolution, the hippie drug culture, and other social influences and changes in American psyche played in the Disco phenomenon. True, all those factors were present, and I leave them to others to debate, but above all, Disco happened the way it did because of the music. The music was the catalyst that sparked the chemical reaction.

As demand for music specifically designed for dancing increased, a new aesthetic emerged. Nothing like it had been heard before. In the three years between the debut of the Disco Action column and the release of Saturday Night Fever in November 1977, the amount of original Disco music released was staggering. Each week a new stack of singles and albums would come on the scene. A door had opened and the new sound of Disco allowed established artists such as Patti LaBelle, the Jackson Five, and Frankie Valli to reinvent themselves, as well as a crowd of great new talent like the Trammps, Donna Summer, and Paul Jabara to rush on to the scene.

Disco distinguished itself from traditional Top 40 songs by experimenting with the length of its tracks. Disco dancers wanted to be fully involved in a song, wrapped up in it. No one knew this better than Tom Moulton, who is universally credited with inventing the extended Disco Mix with his work on early, longer tracks like Peace Pipe by B.T. Express. It became common for a song to be seven or eight minutes long, during which it would break down and then build itself back up to another climax. Eurodisco took it a step further; exploring variations on one songs theme for an entire side of the disc was not unusual. Dancers loved this! Often the floor erupted in screams of joyful approval as the songs progressed. Furthermore, Disco benefited from strides in sound reproduction. The better discos were installing state-of-the-art sound systems. Grinding bass lines, crash cymbals, soaring violins, and tinkling keyboards played at Rock concert volume took dancers inside the sound.

There was one other important element that set the disco experience apart: The songs merged seamlessly. Using two turntables and a mixing console, the DJ could cross-fade between them; as one song faded out, the other faded in. Nonstop music kept dancers on the floor, engaged. Good DJs could calculate which songs to play when and manipulate the crowd into a dancing frenzy. The best could do so while exactly matching the beats, making it sometimes impossible to tell when one song ended and the other began. Thanks to Disco, DJs became artists with followings, stars in their own right.