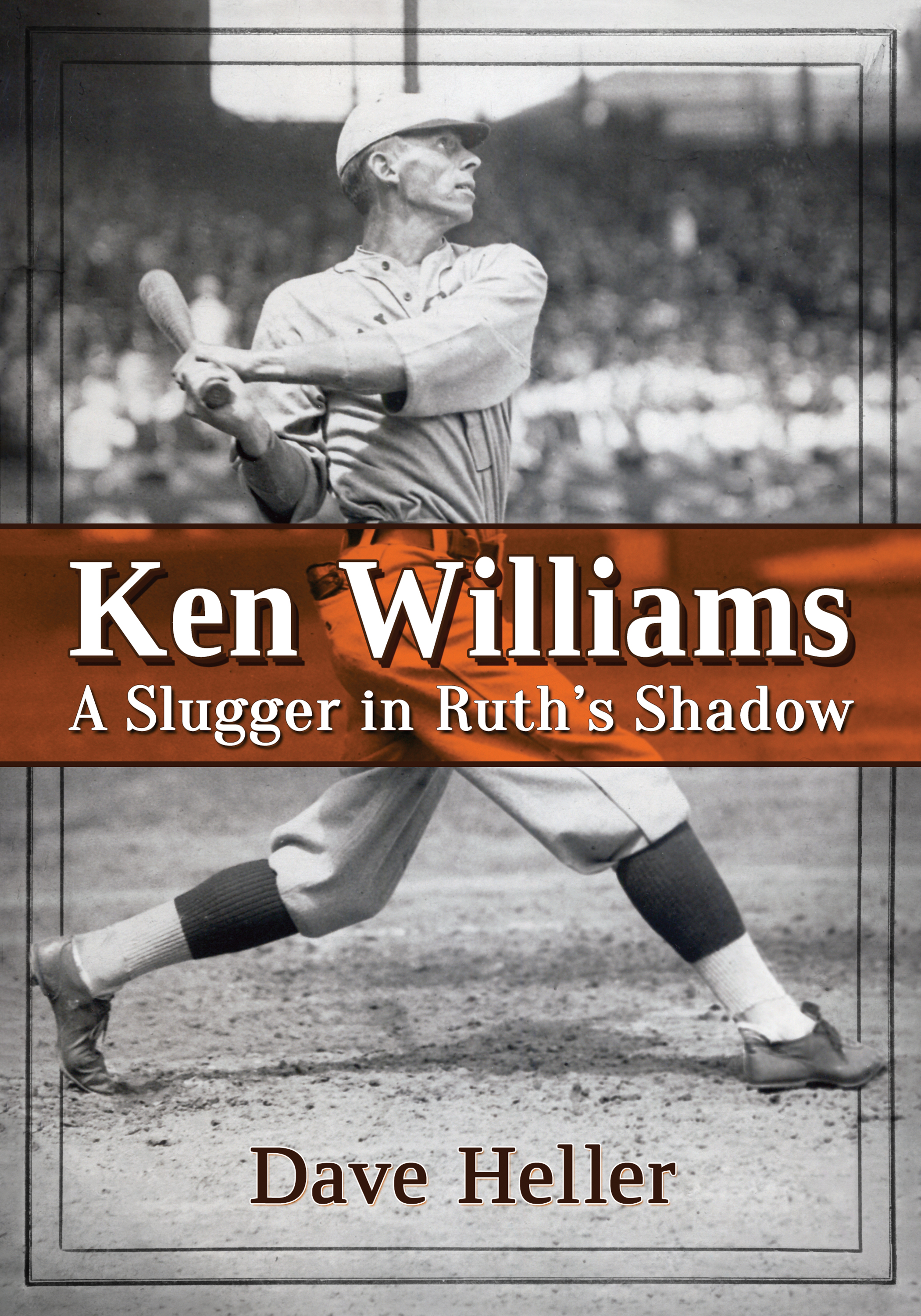

KEN WILLIAMS

A Slugger in Ruths Shadow

Dave Heller

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2583-6

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2017 Dave Heller. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

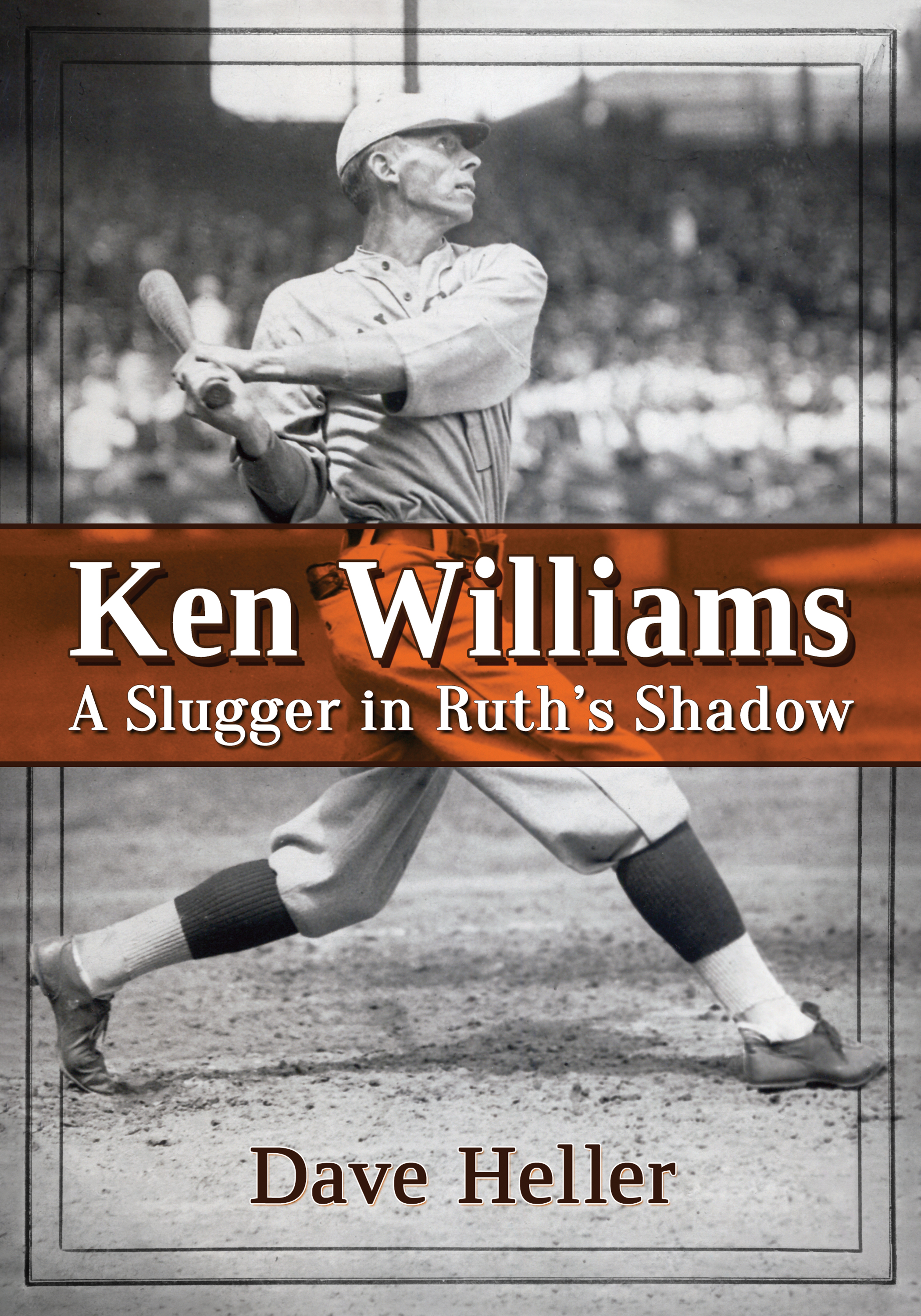

Front cover image of Ken Williams courtesy National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of my grandfathers:

Joe Heller, a sports fan who followed

both the Philadelphia Phillies and As,

and

LaVerne Lyon, a former semi-pro baseball player

and Yankees fan who once saw Babe Ruth bunt for a hit.

Who gives the pesky pill a ride?

And separates it from its hide?

Ken Williams

L.C. Davis, The Sporting News, May 11, 1922

Preface

Many an hour were spent in my youth talking baseball, and a lot of that time revolved around trivia. Whether it was with my brother at home, with friendsor even teachersat school, it was always a good day when I could stump someone.

There were a couple of go-to baseball trivia questions whenever someone new entered the fray. One was: Who was the only player to pinch-hit for Ted Williams? I sometimes amended this to: Who was the only player to pinch-hit for Ted Williams and Roger Maris? It gave it a little more oomph. (The answer: Carroll Hardy.)

The other, more popular question, asked by those who had delved into baseball trivia, was: Who was the first player in history to hit 30 home runs and steal 30 bases in a season? Or, more simply: Who was baseballs first 3030 player? The answer, of course, is Ken Williams. As a kid, that was enough information for most. But not me.

As a lifelong fan of the Baltimore Orioles, I discovered at a young age that they were once the St. Louis Browns. So as someone who quickly became interested in the history of baseball, I became a fan of them as well. (Or, more specifically, since I was born nearly two decades after they left St. Louis, I became interested in their history.) I was the one at the cafeteria lunch table who argued that George Sisler was a better first baseman than Lou Gehrig. Someone had to defend the Browns, I reasoned, and living in Central New York, I was far from anyone else who would do such a thing.

Thus Ken Williams became more than a trivia answer to me. I could look up his statistics in the Baseball Encyclopediathis was the late 1970s and early 1980sbut beyond that, information was hard to come by.

A few decades later, there was still little readily available information about Williams. Most of what I read discounted his slugging feats because of the ballpark he played in, Sportsmans Park in St. Louis, which had a closer-than-usual right-field fence. The left-handed-batting Williams thus could, it was suggested, take advantage of that situation.

But was Williams really just a product of the place where he happened to play the majority of his baseball games? Was his apparent power in fact a mirage? There were other questions, too. Why, for instance, did he get such a late start in the major leagues? Most of his big league career unfolded after he turned 30.

The search was on to find as much about Williams as possible. And thanks to the Age of Information that we live in, many of my questionsincluding those asked abovewere answered.

Williams was not a self-promoter, however, and he seldom talked about himself to others. If asked, hed be happy to talk about the baseball of his day, but otherwise he kept his thoughts to himself. The things that he was never specifically asked about, then, such as why he batted left but threw right, are likely to remain unknown. We can guess, but not even Williamss own sons knew the answer. And nothing in the available sources so much as broaches the subject.

Reputations can sometimes be falsely made. George Sisler was known as a gentlemanly ballplayer, likely because he was a collegian, an all-around good player, and, as star of the team and later manager, more accessible to journalists. Williams was said to be irascible, primarily because he was quick to argue a call with an umpire, and that reputation followed him throughout his career. Williams loved to hit, and if a strike were called on him that he believed to be a ball, hed complain. He would do the same in the field and on the basepaths when calls went against his team. But, except for one instance in semi-pro ball, he never got physical with anyone. (Unlike Sisler, the collegian, who once waved his bat at a pitcher and another time hit an umpire.) The point here is that reputations require careful handling by the biographer, particularly when they took form on the printed page more than 100 years ago.

It has also been reported that Williams was a loner, with few friends or none in baseball. He might have kept things close to the vest, but there is no evidence that he lacked friends or was disliked. In fact, the situation appears to have been quite the opposite. Williams was often asked to play in exhibitions and barnstorm, and even managed one of the teamshardly evidence of someone who had no friends in the game. At old-timers games and reunions, he was right in there mixing it up with former players, not shunned and off in a corner. No one is around to offer first-person accounts and the truth likely, as usual, falls in between, with a mix of reputation, myth and fact.

If there is anything to the belief that Williams was taciturn or moody, could an incident from his first stint in the majors shed light on it?

While some information about him appears to have been lost to time, as it often is for players of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Ive done all that I can to fill in the picture of Williams as both an athlete and a man. In the course of researching this book, I pored over newspapers and magazines from every year of his amateur and professional career, along with those published in the years since. I also spoke with members of the Williams family and dug into the available archival material.

It is my hope that in the pages that follow, the reader will learn much more about Williams than the papers of his day, his contemporaries, or even our advanced statistics alone can reveal.

Chapter 1

Grants Pass and the Semi-Pro Life

They came to see baseball heroes past and present. The dais included Hall of Famers Frankie Frisch, Rogers Hornsby and George Sisler, eventual Hall of Famer Jess Haines, and present-day superstars and future Hall of Famers Stan Musial and Red Schoendienst.

But those at the $10-a-plate dinner honoring the all-time St. Louis all-star team saved their biggest applause of the night for someone who thought hed been forgotten. The former ballplayer, who had played his last game in the major leagues nearly 30 years priorand when he did play, was in the shadow of others who played in St. Louis, Sisler and Hornsby, not to mention the immortal Babe Ruthand who played the majority of his career on a team which no longer existed, took in the unexpected reaction.

Years later in recalling the event, his son, Jack, said his father never thought that people paid that much attention to him. He didnt realize how well known he really was. Ken Williams wasnt forgotten after all.

Next page