Table of Contents

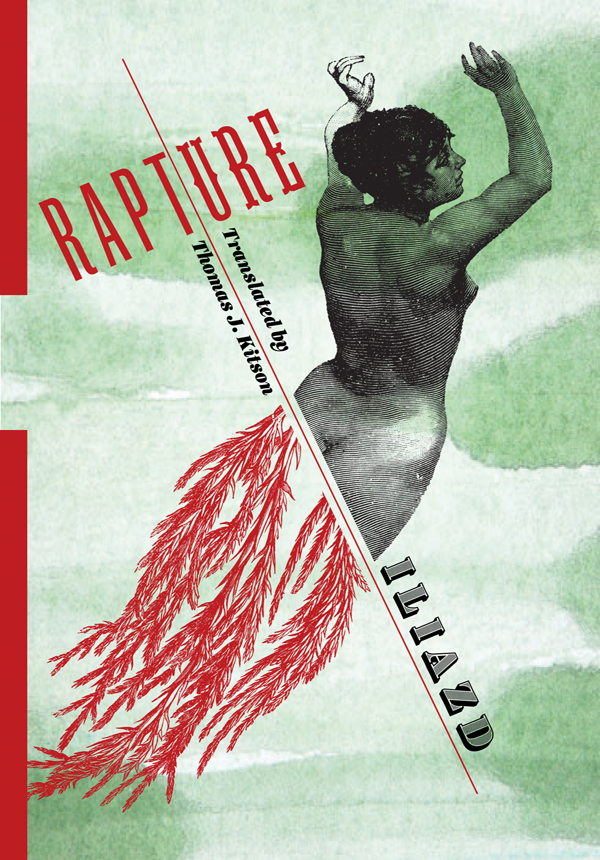

RAPTURE

RUSSIAN LIBRARY

The Russian Library at Columbia University Press publishes an expansive selection of Russian literature in English translation, concentrating on works previously unavailable in English and those ripe for new translations. Works of premodern, modern, and contemporary literature are featured, including recent writing. The series seeks to demonstrate the breadth, surprising variety, and global importance of the Russian literary tradition and includes not only novels but also short stories, plays, poetry, memoirs, creative nonfiction, and works of mixed or fluid genre.

Editorial Board:

Vsevolod Bagno

Dmitry Bak

Rosamund Bartlett

Caryl Emerson

Peter B. Kaufman

Mark Lipovetsky

Oliver Ready

Stephanie Sandler

Between Dog and Wolf by Sasha Sokolov, translated by Alexander Boguslawski

Strolls with Pushkin by Andrei Sinyavsky, translated by Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy and Slava I. Yastremski

Fourteen Little Red Huts and Other Plays by Andrei Platonov, translated by Robert Chandler, Jesse Irwin, and Susan Larsen

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Published with the support of Read Russia, Inc., and the Institute of Literary Translation, Russia

Translation copyright 2017 Thomas J. Kitson

All rights reserved

EISBN: 978-0-231-54329-3

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-231-18082-5 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-231-18083-2 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54329-3 (electronic)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

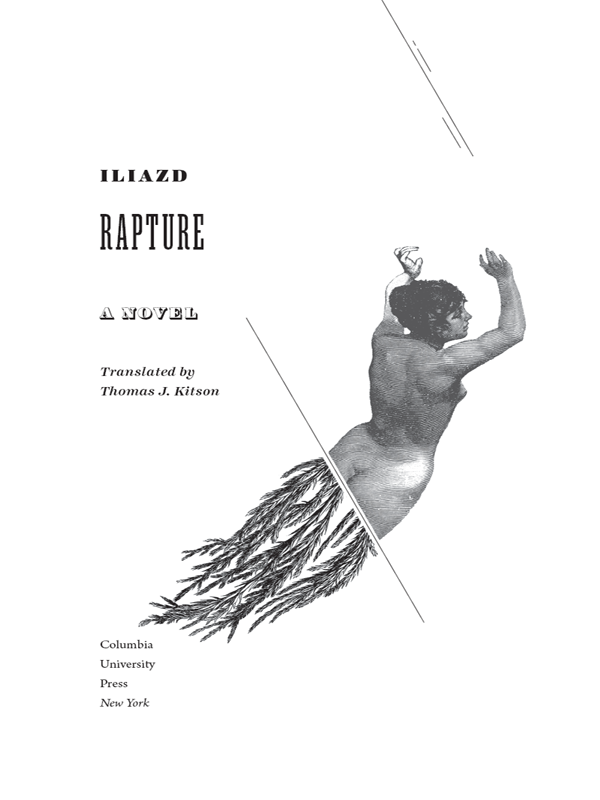

Cover design: Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich

Book design: Lisa Hamm

CONTENTS

PRELUDE

In the years before Iliazds death in 1975, he could be seen strolling through Pariss Latin Quarter, wearing a Caucasian sheepskin coat and holding a shepherds staff. An unusual flock surrounded himthe thirty or so cats that lived in his two-room studio. By then, he had become Frances most revered publisher of the livre dartiste (artists book), working regularly with Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, and Joan Mir. His mysterious ability to herd cats probably reflected the strength of an artistic vision that could integrate such original talents into books that were always, ultimately, by Iliazd. But one suspects that he also identified so closely with his cats for their nine lives, their mythical ability to survive catastrophe and land on their feet, as he had more than once.

Rapture emerged from an earlier exiles life in Paris, virtually unknown to the collectors who treasure Iliazds artistic editions. It is a testament to the survivors ability to reckon up and move on, the reformulation of an artistic credo adopted during an even earlier life lived under another name among Russian avant-garde poets and painters. Iliazd shared with his friend Picasso a deep faith in the artists restlessness and the need to undergo transformation, but he also trusted the power of time to transform artistic objects. A poets best fate is to be forgotten in the expectation of rediscovery by new enthusiasts and interpreters. Rapture is such a neglected treasure.

The great works of avant-garde modernism usually arrived with a bang. Their scandalswhether in the theater, like Alfred Jarrys Ubu Rex, or the courtroom, like Joyces Ulysseshave become integral to the way we think about them. Iliazd was no stranger to scandal. In fact, for a time, his reputation in Russia was based on nothing more than his outrageous lectures and manifestos. Russians even today think first of his extreme experimental dramas written and published during the Russian Civil War. When Iliazd (then still known as Ilia Zdanevich) left the former Russian Empire, he fell effortlessly into the scandalous last Paris Dada soires, where the tactic of shocking the bourgeois had become routine and the Surrealist movement announced itself in violent attacks on the stage.

Rapture did not arrive this way in March 1930. Nor did it meet the eager, protracted anticipation Joyce was able to muster for his work in progress before its final advent as Finnegans Wake. It was ignored. The unassuming yellow-green book, published at Iliazds own expense, went on sale in only one Paris bookstore with a long history of supporting the new art. Within several days, Iliazd had inserted strips of paper into unsold copies with the challenge: Russian booksellers refuse to sell this book. If youre that inhibited, dont read it! Obviously, this was not exactly the usual bang, but it was hardly Eliots whimper.

A world, nevertheless, had ended with the displacements brought on by the 1917 Russian Revolutions. Iliazd had passed, like so many refugees in the aftermath of the First World War, through the chaos of postwar Istanbul and now found himself not just in exile, but even on the margin of the Russian emigr community in Paris. He was cut off from his former associates and not yet fully engaged with the French artists who would become so important to him later. He envisioned Rapture, his first published work of prose fiction, as a final statement on his former life, already delivered with confident hope from inside a new life that was still taking shape.

By coincidence, within weeks of Raptures unremarked release, news of an all-too-final bang reached Iliazd: Vladimir Mayakovsky, the star of the Russian avant-garde, had shot himself through the heart on April 14, 1930, sending a spectacular signal that the old life had indeed come to an end.

On the surface, Rapture takes the form of an adventure novel about Laurence, a treasure-mad young bandit. It tells the story of his doomed love for the mysterious beauty Ivlita and recounts how Laurence establishes a reign of terror over several mountain villages. He then departs with his gang on a series of forays down to the flatlands and the provincial capital, drawn into schemes promising ever larger prizes that turn out to be ever more elusive and evanescent. Laurence leaves a trail of victims and eventually finds himself pursued by government authorities, abandoned by his comrades, and hiding with a pregnant Ivlita in a cave. Finally, Ivlita, too, betrays him. Shortly after being imprisoned, he breaks out with the help of some nameless admirers and sets off to avenge himself on Ivlita. He arrives just in time to see Ivlita die giving birth to their stillborn child, and he succumbs to death beside them.

Ilia Mikhailovich Zdanevich was born in Tiflis (modern Tbilisi), the capital of the Georgian province of the Russian Empire, on April 21, 1894. His father, a teacher of French, came from a Polish family that had been exiled to the area after the Polish uprising of 1830. His mother was a cultured Georgian woman, a former student of Tchaikovsky, and kept her home open to Tifliss artistic and intellectual elite. She also greatly desired a daughter, and in the mythology he later constructed for himself, Zdanevich made much of being treated as a girl well into his childhood.