Also by Stanley Meisler

United Nations: The First Fifty Years

(Reissued in revised and expanded edition as United Nations: A History )

Kofi Annan: A Man of Peace in a World of War

When the World Calls: The Inside Story of the Peace Corps and Its First Fifty Years

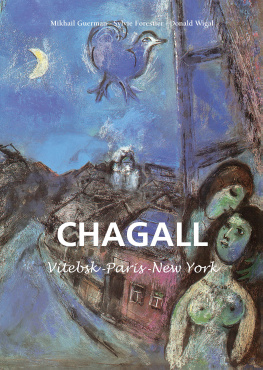

La Ruche (The Beehive), a complex of inexpensive studio apartments subsidized by a French sculptor, was the first stop for Soutine, Chagall and scores of other foreign artists who arrived in Paris in the early years of the twentieth century. Photo Michel LeBrun-Franzaroli.

Shocking P aris

Soutine, Chagall and

the Outsiders of Montparnasse

Stanley Meisler

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillan.com/piracy.

To the memory of

Joyce and Matthew

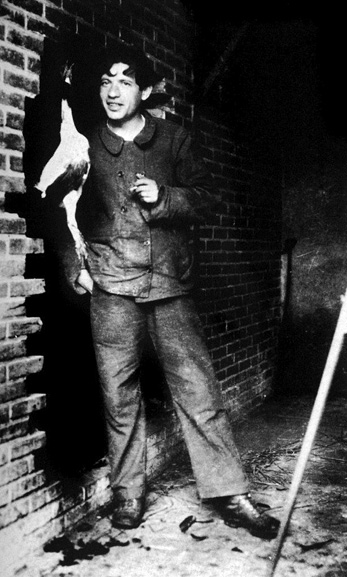

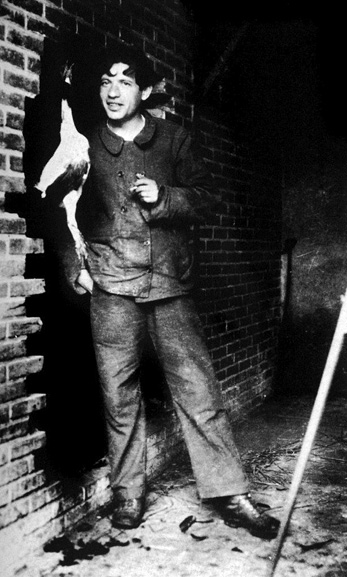

Soutine and a Dead Chicken. The dealer Lopold Zborowski rented a house in the small town of Le Blanc in central France in the late 1920s and invited all his painters including Soutine to spend time there. The dealer encouraged the painting of landscapes, but Soutine was far more interested in still lifes of dead poultry. Private collection/Bridgeman Images.

Contents

Introduction

When I graduated from the City College of New York in 1952, my uncle Morris had words of avuncular wisdom for me. Now that I had a degree, he admonished me, I must work hard, get a steady job and not spend the rest of my life struggling in a Paris garret like his cousin Soutine. Chaim Soutine, the painter? I asked. You mean youve heard of him? replied Uncle Morris.

I dont want to exaggerate my ties to the painter. Uncle Morris was married to my mothers sister. I cannot claim any blood relationship to Soutine. But the little lecture aroused my interest in the dark, enigmatic artist. Whenever I came across a painting by Soutine in a museum from then on, I gave it a second or even a third look.

When the Los Angeles Times assigned me to Paris as its correspondent in the 1980s, it was natural that I would get deeper into the world of Soutine. He is much more celebrated and understood there than in the United States, and I could easily find his statue, his cafs, his homes, even his grave. And, most important, the Orangerie museum on the Place de la Concorde displayed a room full of color-drenched, stunning canvases by Soutine all the time. It was there that I first seemed to see little houses arched and ready to leap from one landscape onto another, a demonstration that this man painted like no one else.

My interest in Soutine led to allied interests, to contemporaries like Chagall and Modigliani and Jules Pascin, to the outpouring of Russian Jewish artists from the Pale of Settlement to Paris, to the Beehive that housed them, to the cafs that fed them, to Dr. Barnes who discovered Soutine, to the School of Paris that comprised these outsiders of Montparnasse and to the critics who castigated them. I wrote about some of these subjects in a small way for both the Los Angeles Times and Smithsonian magazine. It was only in recent years, however, that I understood how all these parts were interrelated, how Dr. Barness championship of Soutine, for example, led to a new gush of contempt for the East European Jews in France. With this understanding came the feeling that it now made sense to write a book connecting many dots of the story.

What I have tried to do in this book is tell the story of the foreign-born immigrant painters in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. Most came from the Russian empire, almost all were Jewish, and they made an impact on the history of art before most Parisians realized they were there. When Parisians did realize it, they were shocked that so much of their cherished world of painting was now in the hands of immigrants. The artists became known as the School of Paris, but they were not a school or a movement in the usual sense. They did not try to produce a certain kind of art. Nor can an art historian discern one characteristic or another that defined them. They were simply a phenomenon of history.

I have tried to tell much of the story through biography, mainly of Soutine with a good deal about Marc Chagall and somewhat less about Amedeo Modigliani and others. Both Soutine and Chagall were Jews who left the Russian empire, but they had nothing else in common. No one could ever mistake the fury of a Soutine painting for the intricate nostalgia of a Chagall. Moreover, their personalities were opposites: Soutine was shy, innocent and often helpless; Chagall was social, savvy and sometimes manipulative. But both were distinguished artists of the twentieth century, and we need to study both to understand the School of Paris.

One of the kindest compliments that I have ever received as a writer came from the late Don Moser. When he retired as editor of Smithsonian magazine, he sent me a note saying that he always had admired my ability to write about art without the usual flapdoodle. By that he meant the opaque jargon and theorizing that often mar the pages of exhibition catalogues and drive readers away from the prose. But there is a danger in turning your back on all jargon and theories, for some opaque prose may contain important issues and insights. On occasion I have felt the need to decipher some opaqueness and translate it into clear sentences for the book. But the result, I hope, is still free of flapdoodle.

Soutine is the key artist in the book, and that creates a temptation. He left no writingno letters, diaries, notebooksabout his art, his personal problems, his feelings about Paris or, in fact, anything else. In her 1993 book on Soutine, French biographer Clarisse Nicodski lamented the difficulty of sorting out the truth when the handful of witnesses contradict each other. The difficulty with Soutine, she wrote, stems from the fact that every testimony, even the most sincere, even the most impartial, is immediately put in question by a detail, an anecdote, another testimony. And that happens not only when it involves setting down the narrative of his life but even more so when describing his way of thinking. That can tempt writers to flights of conjecture. There is an awful lot of prose in art history about what Soutine must have, could have, should have, would have done. I was determined not to follow this lead in the book or, at least, to follow it only rarely. I have avoided conjecture as much as possible.

Finally, the story of the School of Paris, of the foreign immigrant artists of the Russian empire, is part of a much greater story of mass migration from the Russian empire because of religious persecution, political oppression and economic hardship. Many millions were uprooted to America or other parts of Europe. My fathers brother Hona, faced with the draconian quota against Jews in Russian medical schools, left Bialystok (in what is now Poland) to study and then practice medicine in Paris. When he married, he married a doctor in Paris who also came from the Russian empire. One of the official witnesses who signed their certificate was a journalist who knew many artists of the School of Paris. My uncle, my aunt and the reporter all died in Auschwitz. My own father, six years younger than Soutine, left the Russian empire in 1913, the same year as the artist. But my father landed in New York, not Paris.

Next page