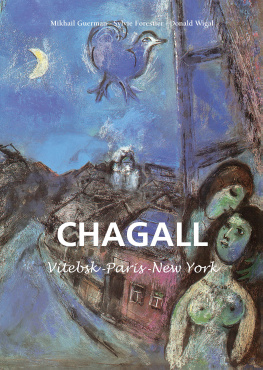

Mikhaïl Guerman - Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York

Here you can read online Mikhaïl Guerman - Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Parkstone International, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

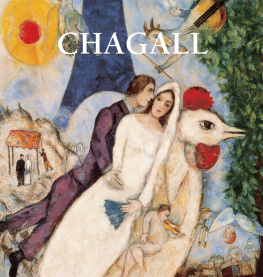

- Book:Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York

- Author:

- Publisher:Parkstone International

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MIKHAIL GUERMAN - SYLVIE FORESTIER

DONALD WIGAL

Marc Chagall

Text: Mikhail Guerman, Sylvie Forestier and Donald Wigal

Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press USA, New York

Marc Chagall Estate, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Image Bar www.image-bar.com

ISBN: 978-1-64461-821-9

All rights reserved.

No parts of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Contents

Through one of those curious reversals of fate, one more exile has regained his native land. Since the exhibition of his work at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow in 1987, which gave rise to an extraordinary popular fervour, Marc Chagall has experienced a second birth.

Here we have a painter, perhaps the most unusual painter of the twentieth century, who at last attained the object of his inner quest: the love of his native Russia. Thus, the hope expressed in the last lines of My Life, the autobiographical narrative that the painter broke off in 1922 when he left for the West perhaps Europe will love me and, along with her, my Russia has been fulfilled.

A confirmation of this is pr-ovided today by the retrospective tendency in his homeland --which, beyond the natural re-absorption of the artist into the national culture, also testifies to a genuine interest, an attempt at analysis, an original viewpoint that enriches our study of Chagall.

Contrary to what one might think, this study is still dogged by uncertainties in terms of historical fact. As early as 1961, in what is still the main work of reference, Franz Meyer emphasised the point that even the establishment of, for example, a chronology of the artists works, is problematic.

In fact, Chagall refused to date his paintings or dated them a posteriori. A good number of his paintings are therefore dated only approximately and to this we must add the problems caused to Western analysts by the absence of comparative sources and, very often, by a poor knowledge of the Russian language.

Therefore, we can only welcome such recent works as that of Jean-Claude Marcad, has underlined the importance of the original source Russian culture for Chagalls work.

One must rejoice even more in the publications of contemporary art historians such as Alexander Kamensky and Mikhail Guerman with whom we now have the honour and pleasure of collaborating.

Yet, Marc Chagall has inspired a prolific amount of literature. The great names of our time have written about his work: from the first serious essay by Efros and Tugendhold, The Art of Marc Chagall, which appeared in 1985, the year of the artists death.

By the occasion of the exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, there had been no lack of critical studies, but all this does not make easy our perception of Chagalls art.

The interpretation of his works now linking him with the Ecole de Paris, now with the Expressionist movement, now with Surrealism seems to be full of contradictions. Does Chagall totally defy historical or aesthetic analysis? In the absence of reliable documents some of which were clearly lost as a result of his travels, there is a danger that any analysis may become sterile.

This peculiarity by which the painters art seems to resist any attempt at theorisation or even categorisation is moreover reinforced by a complementary observation.

The greatest inspiration, the most perceptive intuitions are nourished by the words of poets or philosophers. Words such as those of Cendrars, Apollinaire, Aragon, Malraux, Maritain or Bachelard

Words which clearly indicate the difficulties inherent in all attempts at critical discourse, as Aragon himself underlined in 1945: Each means of expression has its limits, its virtues, its inadequacies.

Nothing is more arbitrary than to try to substitute the written word for drawing, for painting. That is called Art Criticism, and I cannot in good conscience be guilty of that. words that reveal the fundamentally poetic nature of Chagalls art itself.

Even if the arbitrariness of critical discourse appears to be even more pronounced in the case of Chagall, should we renounce any attempt at clarifying, if not the mystery of his work, then at least his plastic experience and pictorial practice? Should we limit ourselves to a mere lyrical effusion of words with regard to one of the most inventive individuals of our time?

Should we abandon research of his aesthetical order or, on the contrary, persist in believing that his aestheticism lies in the intimate and multiform life of ideas, in their free and at times contradictory exchange? If this last is the necessary prerequisite of all advance in thought, then the critical discourse on Chagall can be enriched by new knowledge contributed by the works in Russian collections that have up to now remained unpublished, by archives that have been brought to light and by the testimony of contemporary historians. The comparison gives us a deeper comprehension of this wild art that exhausts any attempt to tame it despite efforts to conceptualise it. About 150 paintings and graphic pieces by Chagall are analysed here by the sensitive pen of the author.

They were all produced between 1906 Woman with a Basket and 1922, the year in which Chagall left Russia for good, with the exception of several later works, Nude Astride a Cockerel (1925), Time is a River without Banks (1930-1939) and Wall-clock with a Blue Wing (1949). The corpus of works presented provides a chronological account of the early period of creativity. The authors analysis stresses with unquestionable relevance the Russian cultural sources on which Chagalls art fed.

It reveals the memory mechanism that lies at the heart of the painters practice and outlines a major concept. It is tempting to say a major tempo, that of time-movement is perceptible in the plastic structure of Chagalls oeuvre. Thus we can much better understand the vivid flourishing of the artists work with its cyclical, apparently repetitive (but why?) character, which might be defined as organic and which calls to mind the ontological meaning of creation itself as set out in the writings of Berdiayev.

This primordial outpouring of creativity that brought the admiration of Cendrars and Apollinaire, this imperious pictorial paganism that dictates its own law to the artist, sets forth an aesthetic and an ethic of predestination that we would like to clarify. It is in the immediacy of Chagalls pictorial practice, in the immediacy of each creative decision that his own identity lies, that he himself is to be found. This self-revelation is related to us by Chagall himself. The autobiographical My Life, written in Russian, first appeared in 1931 in Paris, in a French translation by Bella Chagall. Providing us with extremely precious evidence of a whole part of the artists life, this text tender, alert and droll reveals behind its anecdotal nature the fundamental themes of his work and above all, its problematic character. The tale as a whole is not moreover without some evocations of the artists biographies studied by Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz who set out a typology.

From the first lines ones attention is attracted by a singular phrase: That which first leapt to my eyes was an angel! Thus, the first hours of Chagalls life were registered here specifically in visual terms. The tale begins in the tone of a parable and his life-story could not belong to anyone but a painter. Chagall, who recalls the difficulties of his birth, writes: But above all I was born dead. I did not want to live. Imagine a white bubble which does not want to live. As if it were stuffed with paintings by Chagall.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York»

Look at similar books to Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Marc Chagall - Vitebsk -París -New York and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.