Table of Contents

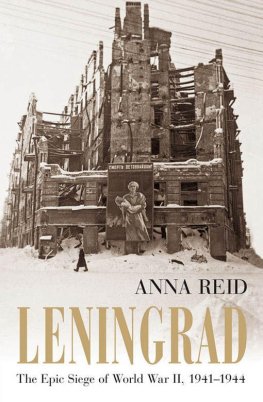

Also by Michael Jones

The Kings Mother

Bosworth 1485 - Psychology of a Battle

Agincourt 1415 - A Battlefield Guide

Stalingrad: How The Red Army Triumphed

For Edmund and Rufus

List of Illustrations

1. A self-portrait of Elena Martilla - from the first winter of the Leningrad blockade

2. First casualties of the siege

3. Marshal Kliment Voroshilov

4. A Leningrad apartment during the siege

5. Big piece of bread! was all Alik could say

6. The alert will soon be over

7. What are you doing to us?

8. A Leningrader sits amid the wreckage of her home

9. The agony of the siege: a mother buries her child

10. If we die, we die together

11. On duty

12. The Leningrad Madonna

13. A devastated landscape

14. A Leningrad siege diary and its teenage author

15. Gathering water under the ice of the Neva

16. In the Public Library

17. Scene from a Leningrad starvation hospital

18. One February night Elena Martilla summoned all her remaining strength and painted this self-portrait

19. I cannot count the riches of my soul - the poetry of Olga Berggolts

20. Motorised sledges - manned by Red Army soldiers - fan out to protect the Road of Life

21-22. Lorries carrying precious food and supplies for Leningrad roll forward across frozen Lake Ladoga

23. A driver takes a lorry - load of refugees across the Road of Life

24. Andrei Zhdanov looks distinctly overweight as he visits front-line troops

25. An emaciated actor from the Musical Comedy Theatre still transmits extraordinary energy to his audience

26-27. On 27 March 1942 an army of Leningrad women moves into action and the great city clean-up begins

28. Lieutenant-General Govorov - the real hero of the siege - inspects an artillery position

29. Tanya Savicheva sways in a terrible trance, cradling a dying house plant which holds the memory of her lost family

30. Karl Eliasberg conducts the Radio Committee Orchestra at the Philharmonic - probably for Shostakovichs Seventh Symphony on 9 August 1942

31. Enthralled by the music - the audience pack Leningrads Philharmonic Hall for the performance of Shostakovichs Seventh

32. We defended Lenins city!

33-34. 27 January 1944 - the 872-day siege is finally over

35. An eternal flame burns in the Piskaryov Memorial Cemetery

Acknowledgements: I am profoundly grateful to Elena Martilla, who allowed me unlimited use of her siege drawings (1, 4-7, 10-13, 16, 18- 19, 23, 29) and to the Director of the Museum of the Blockade, St Petersburg, for permission to reproduce the photographs (2-3, 8-9, 14-15, 17, 20-22, 24-28, 30-34). The curator of the museums archive kindly found the photographs of the performance of Shostakovichs Seventh. The photo of the Piskaryov Cemetery (35) was taken by me.

Preface

In early September 1941 Hitlers armies cut the last roads leading into besieged Leningrad (now St Petersburg) and, in the words of the poet Olga Berggolts, the noose of the blockade tightened around the citys throat. There followed the most horrific siege in history.

This book grew out of my work as a battlefield guide on the Second World Wars Eastern Front. I am grateful to Midas and Holts Battlefield Tours, who helped set up the Siege of Leningrad tour, and to Oleg Alexandrov, of our associated Russian travel company, who first facilitated meetings with Red Army veterans of the fighting. I want to take my readers on a journey, allowing them to experience the exceptional power of this story - its sheer horror, but also its capacity to inspire and move us.

My understanding of the siege is informed not by official Soviet records of the peoples valour but by actual accounts of those trapped in the city. I am deeply grateful to three veterans who have been a constant source of encouragement and support: Svetlana Magaeva, who generously gave me access to her psychological profiles of siege survivors; artist Elena Martilla, who allowed me to use her remarkable collection of sketches - drawn during the blockade - and Irina Skripachyova, head of the St Petersburg Siege Veterans Association, who arranged countless meetings for me. All have enormously enhanced this work.

I use an interview process that I employed with Red Army veterans in my previous book on the battle of Stalingrad, building up a rapport and then working together to establish the psychological contours of the story. I am deeply grateful to the siege survivors who have shared their experiences with me and who have pointed me towards diaries - published and unpublished - that are honest about the horror descending on the city. Their many contributions are acknowledged in the endnotes. A particularly moving meeting was with survivors of the Lychkovo train massacre on their first ever reunion, in March 2007.

Others have perished, and can speak to us only through their personal papers. I owe another debt of thanks to the director of the Blockade Museum for allowing me access to its many siege diaries and letters. Olga Prut, who oversees the Museum The Muses Were Not Silent, dedicated to cultural life during the siege, and especially the performance of Shostakovichs Seventh, and musicologist Professor Andrei Krukov, have kindly given me additional material.

I also draw on accounts already published. The siege diaries of Vera Inber, Elena Kochina and Elena Skrjabina exist in translation, as does the groundbreaking compilation by Ales Adamovich and Daniil Granin, A Book of the Blockade. Cynthia Simmons and Nina Perlina have also brought out an important collection of siege experiences. More is available in Russian, and fresh material is emerging all the time - the most recent, from the Centre for Oral History at the European University of St Petersburg, came out in 2006. And I have greatly benefited from the major research on the siege undertaken by Richard Bidlack and Nikita Lomagin.

Lena Yakovleva undertook translation and interpretation work in Moscow, and Anna Artiushina did the same in St Petersburg, as well as locating many valuable references for me. Caroline Walton made a number of additional translations and kindly provided me with extracts from Alexander Boldyrevs diary. David M. Glantz and Albert Axell have also helped me with a number of specific points. In general I have followed sources transliterations from Cyrillic script, although on occasions I have standardised spellings of forenames and word endings.

I am grateful to David Glantz for background material on the city map of Leningrad, and to Svetlana Magaeva and Albert Pleysier for help with the maps of the siege lines and the Road of Life. The German advance is drawn from information in Leon Goures The Siege of Leningrad; the dispositions in Operation Spark are from Robert F. Baumanns Operation Spark: breaking through the siege of Leningrad, in Combined Arms in Battle since 1939, ed. Roger J. Spillar (Fort Leavenworth, 1992).

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to my agent, Charlie Viney, and to Roland Philipps and Rowan Yapp at John Murray, for their encouragement and support as this work developed. The first three chapters of the book are thematic, and look at the period leading up to the siege of Leningrad from the point of view of the advancing Germans, the Soviet authorities defending the city and finally the ordinary civilians. The subsequent chapters follow a roughly chronological sequence. Their focal point is the three-month period from mid-December 1941 to mid-March 1942 when conditions within Leningrad were at their worst.