All primary source documents have been reprinted with the permission of their authors.

FOREWORD: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO THE SIEGE OF LENINGRAD

RICHARD BIDLACK

I wish to thank the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) and the Dean's Office of Washington and Lee University for supporting the research on which this foreword is based.

THE SIEGE OF LENINGRAD BY GERMAN AND FINNISH ARMIES DURING World War II was one of the most horrific events in world history. According to the most recent and reliable estimate, fighting in the Leningrad area from the summer of 1941 to the summer of 1944 and during the 872 days of blockade and bombardment of the city itself took the lives of somewhere between 1.6 and 2 million Soviet citizens (not to mention enemy casualties). The entire range of this estimate exceeds the total number of Americans, including military personnel and civilians, who have perished in all wars from 1776 to the present. The exact death toll, however, may have been considerably higher.

The prolonged siege possessed elements of epoch, epic, and monumental tragedy that transcend the temporal and spatial boundaries of World War II. For the USSR at war, the defense of Leningrad held strategic significance. It was one of the nation's largest centers for manufacturing munitions. More important, however, is the fact that if Leningrad had fallen in the late summer or early autumn of 1941, Germany could have redirected hundreds of thousands of additional troops and war machines toward Moscow. If Moscow had in turn been taken in short order, the war might have ended. Holding on to Leningrad and defending the eastern adjacent region of Karelia also protected the lend-lease corridor southward from Murmansk. Although American-manufactured lend-lease materials played little role in Sovietdefense through 1942, they did greatly facilitate the eventual Soviet triumph on the eastern front.

Victory in the Great Patriotic War (to use Soviet parlance that has carried over to the present in Russia) became an integral part of the USSR's self-justification and propaganda. On average, about one book per day on the war was published in the USSR between 1945 and 1991. These works, though often rich in detail, followed prescribed themes and were subjected to heavy censorship. Soviet-era books on wartime Leningrad number about four hundred. Few of them were published before the death of Stalin, who always regarded the second capital with suspicion. Outside of Russia, the best general histories of the siege are Leon Goure's The Siege of Leningrad and Harrison Salisbury's outstanding best-seller, The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad.

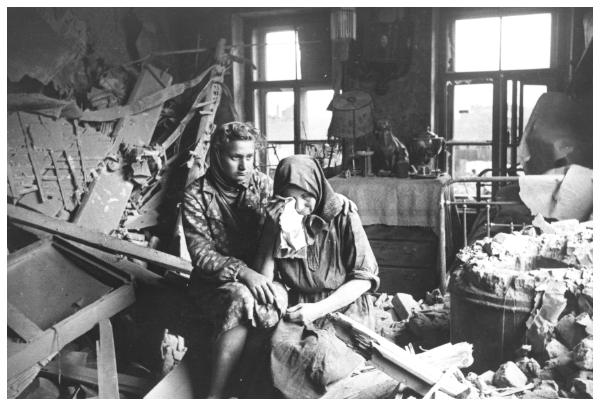

A conspicuous void, however, has remained in the historical literature: description and analysis that focus specifically on the activities and attitudes of women, who made up a large majority of Leningrad's civilian population during the siege. The diaries, letters, memoirs, oral accounts, and accompanying commentary assembled here in Writing the Siege of Leningrad help fill that void. Several memoirs and diaries have been published in English by female siege survivors, but what has been missing before Writing the Siege of Leningrad is a scholarly work in any language that attempts to define female perspectives on the siege and to trace those perspectives through a number of first-hand accounts. Writing the Siege of Leningrad is also a very timely book, because it contains many accounts based on recent interviews. The number of blockade survivors is dwindling rapidly, and their personal histories need to be written down while there is still time.

To understand the type of city that Leningrad was at the start of the Soviet-German War and how women came to play a major role in sustaining the city during the siege, one has to go back to at least 1929. That year marked the start of Stalin's programs for rapid construction of the nation's heavy industrial base in the First Five-Year Plan and collectivization of agriculture. Hundreds of thousands of peasants fled the mass starvation that followed state seizure of their land. Many were drawn to the new and expanded factories in heavily industrialized Leningrad, where they couldreceive both a salary and a food ration card. Rapidly rising prices, caused by the famine and a severe shortage of consumer goods, meant that families generally needed a second salary to make ends meet. This prompted many women who had not previously worked outside the home to enter the city's work force. The expanded educational opportunities of the early Soviet decades also enabled women to seek employment in many new fields.

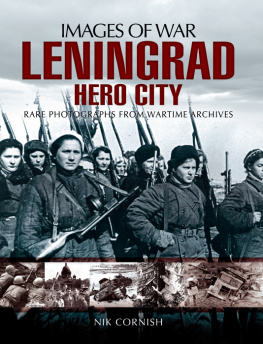

In the late 1930s political terror swept through Leningrad. Whether or not Stalin actually ordered the murder of Sergei Kirov, Leningrad's Communist Party leader, on 1 December 1934, he used the murder as a reason or pretext to purge thoroughly the city's party organization and industrial elite. By 1937 and 1938, the purges had become widespread in Leningrad. Most of those arrested were men, which created more jobs for their wives, widows, sisters, and daughters. Work opportunities for women increased further between 1938 and the first half of 1941, because many new defense plants were opened in Leningrad during the Third Five-Year Plan. By 1940, Leningrad was producing approximately 10 percent of the nation's total industrial output in more than six hundred factories, and women made up some 47 percent of the city's industrial work force, which comprised about 750,000 people altogether.

Soviet histories of the war exaggerated the changes that took place following the start of the German invasion by implying that the USSR had previously been a society at peace. In fact, Leningrad's economy was highly mobilized and militarized in 1939 and 1940. The Soviet Union attacked several nations during the two years of the alliance with Nazi Germany. Leningrad served as the arsenal for the offensive war against Finland during the winter of 19391940 (which claimed the lives of at least 127,000 Soviet military personnel); fighting in the Winter War took place just north of the city. Once again, more women went to work in Leningrad's factories to replace men who had been drafted into the armed forces. Contending with shortages that accompanied the war economy in 19391941 provided specific lessons for Leningraders that would prove useful during the siege years. At the same time, however, the fact that production of goods and services for the civilian population had been sacrificed to expand military production before 1941 made it that much more difficult for Leningraders to bear further militarization of their economy during the war with Germany.

Leningrad was experienced in preparing for war and waging it before 1941, and a series of new, massive mobilization drives commenced as soon The volunteers received little or no training and were often armed only with hunting rifles, hand grenades, or bottles filled with gasoline. Their mission was to stop the advance of the armored divisions of German Army Group North. It is no wonder that the volunteers suffered extraordinarily high casualty rates. Another 14,000 Leningraders, mainly men, were trained as partisans and sent behind enemy lines.