LENINGRAD

The Epic Siege of World War II, 19411944

Anna Reid

For Edward and Bertie

Contents

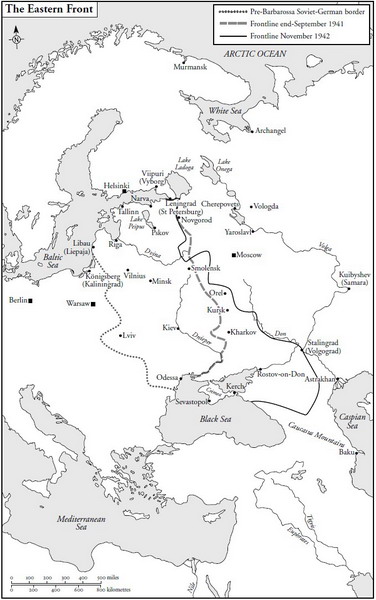

This is the story of the siege of Leningrad, the deadliest blockade of a city in human history. Leningrad sits at the north-eastern corner of the Baltic, at the head of the long, shallow gulf that divides the southern shores of Finland from those of northern Russia. Before the Russian Revolution it was the capital of the Russian Empire, and called St Petersburg after its founder, the tsar Peter the Great. With the fall of Communism twenty years ago it regained its old name, but for its older inhabitants it is Leningrad still, not so much for Lenin as in honour of the approximately three-quarters of a million civilians who starved to death during the almost nine hundred days from September 1941 to January 1944 during which the city was besieged by Nazi Germany. Other modern sieges those of Madrid and Sarajevo lasted longer, but none killed even a tenth as many people. Around thirty-five times more civilians died in Leningrad than in Londons Blitz; four times more than in the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima put together.

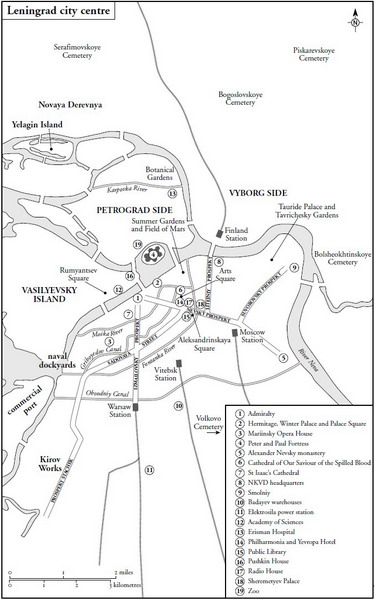

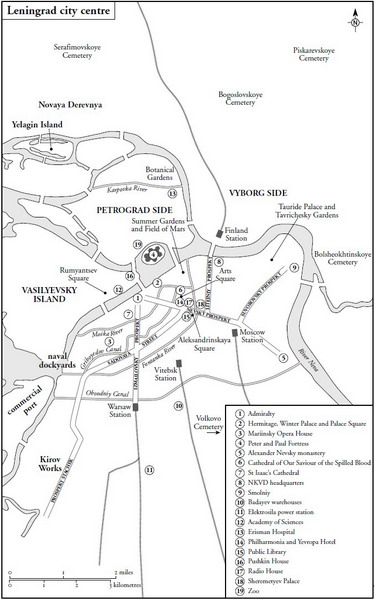

On 22 June 1941, the midsummer morning on which Germany attacked the Soviet Union, Leningrad looked much the same as it had done before the Revolution. A seagull circling over the gilded needle of the Admiralty spire would have seen the same view as twenty-four years previously: below the choppy grey River Neva, lined by parks and palaces; to the west, where the Neva opens into the sea, the cranes of the naval dockyards; to the north, the zigzag bastions of the Peter and Paul Fortress and grid-like streets of Vasilyevsky Island; to the south, four concentric waterways the pretty Moika, coolly classical Griboyedov, broad, grand Fontanka and workaday Obvodniy and two great boulevards, the Izmailovsky and the Nevsky Prospekt, radiating in perfect symmetry past the Warsaw and Moscow railway stations to the factory chimneys of the industrial districts beyond.

Appearances, though, were deceptive. Outwardly, Leningrad was not much altered; inwardly, it was profoundly changed and traumatised. It is conventional to give the story of the blockade a filmic happy-sad-happy progression: the peace of a midsummer morning shattered by news of invasion, the call to arms, the enemy halted at the gates, descent into cold and starvation, springtime recovery, victory fireworks. In reality it was not like that. Any Leningrader aged thirty or over at the start of the siege had already lived through three wars (the First World War, the Civil War between Bolsheviks and Whites that followed it, and the Winter War with Finland of 193940), two famines (the first during the Civil War, the second the collectivisation famine of 19323, caused by Stalins violent seizure of peasant farms) and two major waves of political terror. Hardly a household, particularly among the citys ethnic minorities and old middle classes, had not been touched by death, prison or exile as well as impoverishment. For someone like the poet Olga Berggolts, daughter of a Jewish doctor, it was not unduly melodramatic to state that we measured time by the intervals between one suicide and the next. The siege, though unique in the size of its death toll, was less a tragic interlude than one dark passage among many.

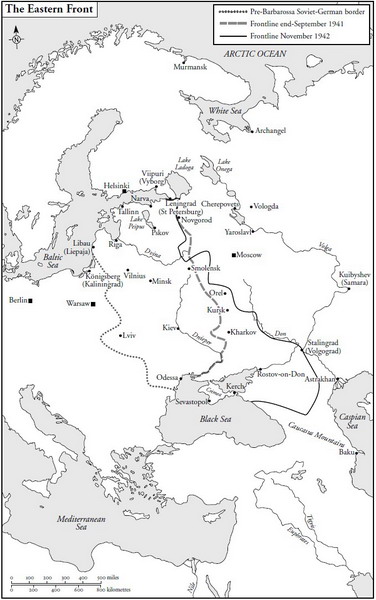

The tragedy arose from the combined hubris of Hitler and Stalin. In August 1939 they had astonished the world by putting ideology aside to form a non-aggression pact, under which they divided Poland between them. When Hitler turned on France the following spring Stalin stood aside, continuing to supply his ally with grain, metals, rubber and other vital commodities. Though it is clear from what we now know of Stalins conversations with his Politburo that he expected to be forced into war with Germany sooner or later, the timing of the Nazi attack code-named Barbarossa or Redbeard after a crusading Holy Roman Emperor came as a devastating shock. The new, poorly defended border through Poland was overrun almost immediately, and within weeks the panic-stricken Red Army found itself defending the major cities of Russia herself.

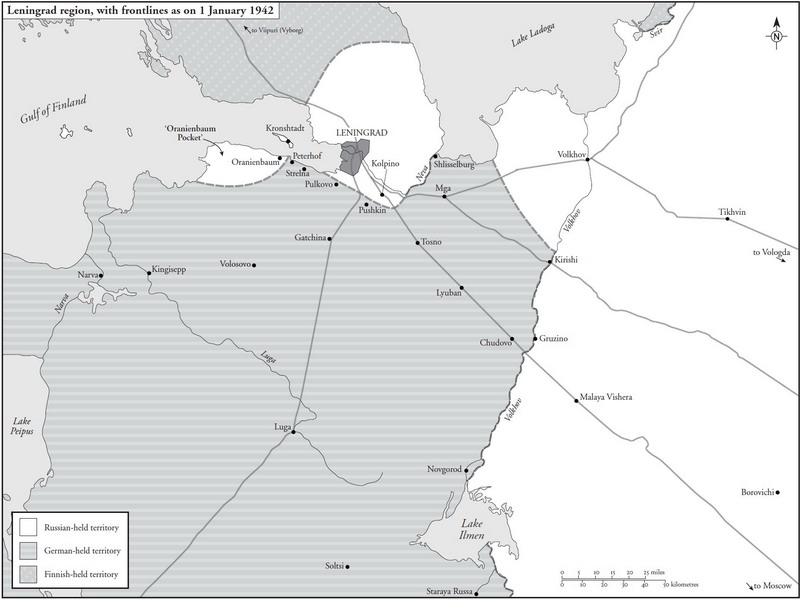

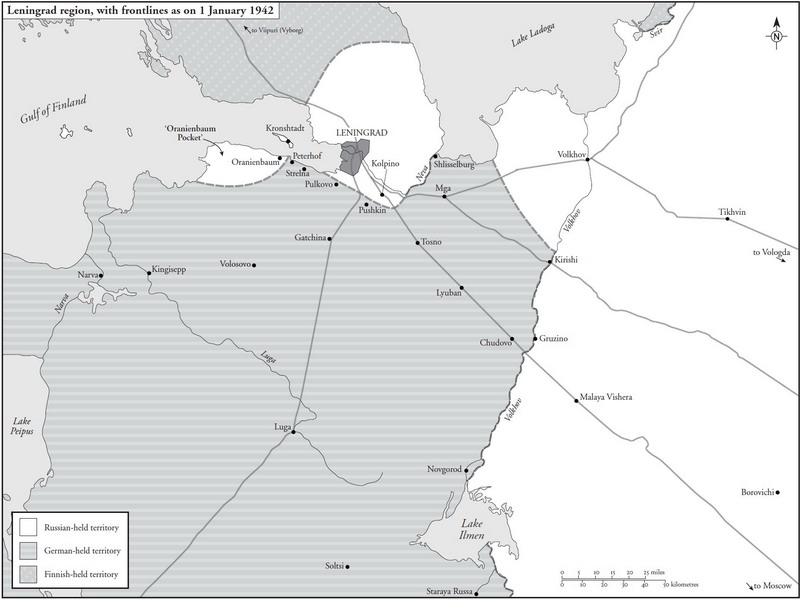

Chief victim of this unpreparedness was Leningrad. Immediately pre-war, the city had a population of just over three million. In the twelve weeks to mid-September 1941, when the German and Finnish armies cut it off from the rest of the Soviet Union, about half a million Leningraders were drafted or evacuated, leaving just over 2.5 million civilians, at least 400,000 of them children, trapped within the city. Hunger set in almost immediately, and in October police began to report the appearance of emaciated corpses on the streets. Deaths quadrupled in December, peaking in January and February at 100,000 per month. By the end of what was even by Russian standards a savage winter on some days temperatures dropped to -30C or below cold and hunger had taken somewhere around half a million lives. It is on these months of mass death what Russian historians call the heroic period of the siege that this book concentrates. The following two siege winters were less deadly, thanks to there being fewer mouths left to feed, and to food deliveries across Lake Ladoga, the inland sea to Leningrads east whose south-eastern shores the Red Army continued to hold. In January 1943 fighting also cleared a fragile land corridor out of the city, through which the Soviets were able to build a railway line. Mortality nonetheless remained high, taking the total death toll to somewhere between 700,000 and 800,000 one in every three or four of the immediate pre-siege population by January 1944, when the Wehrmacht finally began its long retreat to Berlin.

Remarkably, the siege of Leningrad has been paid rather little attention in the West. The best-known narrative history, written by Harrison Salisbury, a Moscow correspondent for the New York Times , was published in 1969. Military historians have concentrated on the battles for Stalingrad and Moscow, despite the fact that Leningrad was the first city in all Europe that Hitler failed to take, and that its fall would have given him the Soviet Unions biggest arms manufacturies, shipyards and steelworks, linked his armies with Finlands, and allowed him to cut the railway lines carrying Allied aid from the Arctic ports of Archangel and Murmansk. More generally, the siege remains lost in the gloomy vastness of the Eastern Front an empty, snow-swept plain, in the public imagination, across which waves of Red Army conscripts stumble, greatcoats flapping, towards massed German machine guns. Worryingly often, during the writing of this book, friends turned out to think that Leningrad (on the Baltic, now called St Petersburg) and Stalingrad (a third of the size, near the present-day border with Kazakhstan, now called Volgograd) were actually the same place.

A slightly different form of vagueness afflicts Germans, for whom the Eastern Front was regarded until recently as a scene of military suffering rather than atrocity. Millions of Germans have to live with the fact that a parent or grandparent was a member of the Nazi Party; millions more have a father or grandfather who fought in Russia. It is easier to remember that they were frostbitten and frightened, or starved and put to forced labour in prisoner-of-war camps (almost four in ten of the 3.2 million Axis soldiers taken prisoner by the Soviets died in captivity Strolling around the lovely medieval city of Freiburg, home to Germanys military archives, one comes across small brass plaques, engraved with names and dates, set into the pavement. They mark the houses from which local Jewish families were deported to the concentration camps. Leningrads women and children, murdered by the same regime with equal deliberation, suffered out of sight and to this day largely out of mind.

Next page