CONTENTS

For my mother

and

my sister

For absent friends

So is there no fact, no event, in our private history,

which shall not, sooner or later, lose its adhesive,

inert form, and astonish us by soaring from our

body into the empyrean? Cradle and infancy,

school and playground, the fear of boys, and

dogs, and ferules, the love of little maids and

berries, and many another fact that once filled

the whole sky, are gone already; friend and

relative, profession and party, town and

country, nation and world, must also soar

and sing.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON,

The American Scholar

PROLOGUE

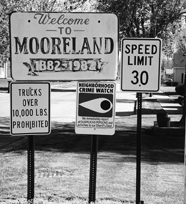

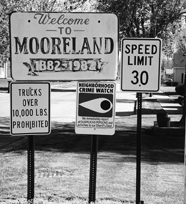

I f you look at an atlas of the United States, one published around, say, 1940, there is, in the state of Indiana, north of New Castle and east of the Epileptic Village, a small town called Mooreland. In 1940 the population of Mooreland was about three hundred people; in 1950 the population was three hundred, and in 1960, and 1970, and 1980, and so on. One must assume that the number three hundred, while sacred, did not represent the same persons decade after decade. A mysterious and powerful mathematical principle was at work, one by which I and my family were eventually governed. Old people died and new people were added, and thus what was shifting remained constant.

I got to be new there. I was added and shortly afterward the barber named Tony was taken away. This was in 1965. The distance between Mooreland in 1965 and a city like San Francisco in 1965 is roughly equivalent to the distance starlight must travel before we look up casually from a cornfield and see it. Sociologists and students of history imagine they know something of the United States in the sixties and seventies because they are familiar with the prevailing trends; if they drew assumptions about Mooreland based on that knowledge, they would get everything wrong. Strangely, there has never been a definitive source of information about Mooreland during a certain fifteen-year period, perhaps because there are so few people left who can reliably tell it. Many have been added since then. Many have moved on.

Not long ago my sister Melinda shocked me by saying she had always assumed that the book on Mooreland had yet to be written because no one sane would be interested in reading it. No, no, wait, she said. I know who might read such a book. A person lying in a hospital bed with no television and no roommate. Just lying there. Maybe waiting for a physical therapist. And then here comes a candy striper with a squeaky library cart and on that cart there is only one bookor maybe two books: yours, and Cooking with Pork. I can see how a person would be grateful for Mooreland then.

Everyone familiar with my childhood in Mooreland agreed with Melindas position. One woman even said that Mooreland is a long way to go not to be anywhere when you get there, and yet I persisted. I felt that there was so much more to the town than its trappings. There was one main street, Broad Street, which was actually not so broad, and was the site of the towns only four-way stop sign. There were three churches: the North Christian Church and the South Christian Church, which sat at opposite ends of Broad Street like sentinels, and the Mooreland Friends Church, which was kind of in the middle of town, but tucked back on Jefferson Street at the edge of a meadow. There were no taverns, no theaters, no department stores. If a man was interested in drinking, he had to travel to Mt. Summit, to the aptly named Dog House, or to the Package Liquor Store in New Castle, about ten miles away. New Castle was, in fact, the hub of all our commercial activity, and it had everything: a fabric store, Grants Department Store, the Castle Theater (which showed a single movie at a time, second-run, the same movie for weeks running), Becker Brothers Grocery. In Mooreland we had our own gas station and our own drugstore, where we could buy a fountain soda but no drugs. (For a while Mooreland had an actual doctor, and we could buy drugs from him, but the police eventually came and took him away.) When I was little there was a hardware store, and off and on there was a diner in what used to be somebodys house. These days its a house again. We had a veterinarian, who could treat little animals, like cats and dogs, and big ones, like horses and cows. Mooreland was bordered at the north end by a cemetery and at the south by a funeral home. The spirit of the place, if such spirits can be said to exist, was the carnival, Poor Jack Amusements, that arrived at the end of the harvest season every August. Most people took their vacations during the week of the fair, and were there morning to night, working in a food tent or organizing one of the events, like the Horse and Pony Pull, or the Most Beautiful Baby Contest. Everyone in Mooreland believed in God (except my dad). There was no such thing as multiculturalismno people of color, no exotic religions, no one openly homosexual (there was one old bachelor who had suspiciously good taste in furniture, but we didnt question his private life).

My parents moved to Mooreland with my brother and sister in 1955, five years after they married. (Prior to living in Mooreland they had lived in the very, very big town of Muncie; I assume those were The Dark Years.) I wasnt born until 1965, when my brother was thirteen and my sister nearly ten. My mother always cheerfully refers to me as an afterthought, which I consider a term of immense respect and affection, in spite of Melindas attempts to convince me otherwise.

The book that follows is about a child from Mooreland, Indiana, written by one of the three hundred. Its a memoir, and a sigh of gratitude, a way of returning. I no longer live there; I cant speak for the town or its people as they are now. Someone has taken my place. Whoever she is, her stories are her own.

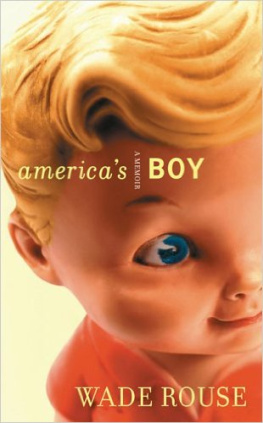

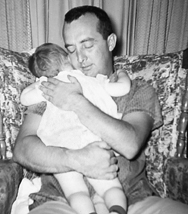

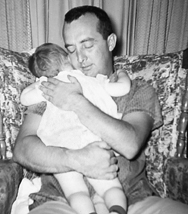

BABY BOOK

T he following was recorded by my mother in my baby book, under the heading MILESTONES:

FIRST STEPS: Nine months! Precocious!

FIRST TEETH: Bottom two, at eight months. Still nursing her, but she doesnt bite, thank goodness!

FIRST SAYS MOMMY: (blank)

FIRST SAYS DADDY: (blank)

FIRST WAVES BYE-BYE: As of her first birthday, she is not much interested in waving bye-bye.

At age eighteen months, the baby book provided a space for FURTHER MILESTONES, in which my mother wrote:

Shes still very active and energetic. Her daddy calls her Zippy, after a little chimpanzee he saw roller-skating on television. The monkey was first in one place and then zip! in another. Has twelve teeth. Im still nursing hershes a thin baby, and it cant hurtbut Im thinking of weaning her to a bottle. Theres no sense in trying to get her to drink from a cup. Still not talking. Dr. Heilman says she has perfectly good vocal cords, and to give it time.

On my second birthday:

Still no words from our little Zippy. She is otherwise a delight and a very sweet baby. I have turned her life over to God, to do with as He sees fit. I believe He must have a very special plan for her, because Im sure that terrible staph infection in her ear that nearly killed her when she was a newborn must have, as the doctors feared, reached her brain. She is so quiet we hardly know she is here, and so unlike many of our friends, we can speak freely in front of her without fear she will repeat us. Little Becky Dawson walked up to Agnes Johnson in church last Sunday and called her Broad As A Barn. You know she heard that at home. We are very grateful for our little angel on her second birthday.

Next page