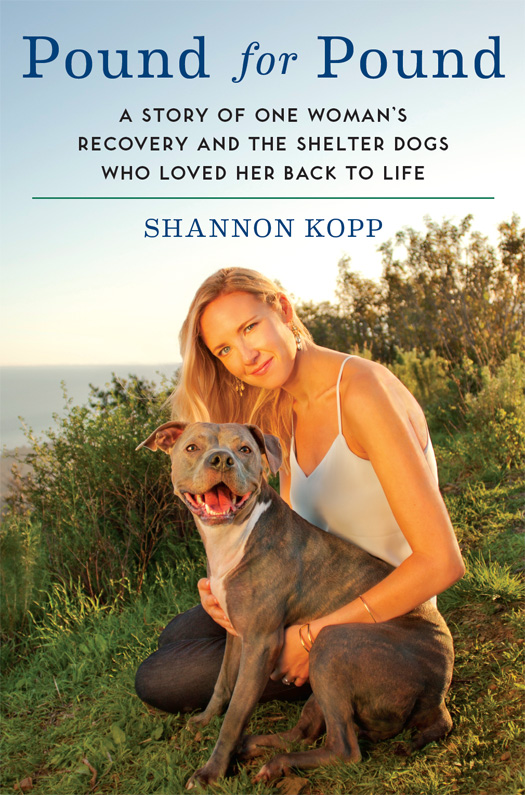

T HIS IS A true story constructed from my memory and personal journals. Ive changed the names and identifying characteristics of some people who appear in my book. I have also withheld the name of an animal shelter and changed some orienting details associated with it, so as not to create controversy that might impact their vital fund-raising efforts.

In 1984, an estimated 17 million animals were killed every year in Americas shelter system. Today, thanks to the hard work of many animal lovers, and organizations like Best Friends Animal Society, that number has decreased to 4 million. Still, the tragic reality remains that 9,000 dogs and cats are euthanized daily in U.S. shelters.

Id like to thank the many shelter staff and volunteers Ive met over the years, from veterinarians to humane investigations officers to animal caregivers to humane educators, who are working tirelessly to end the suffering and euthanasia of adoptable animals in America. You are true heroes, warriors of the heart. May your passion, courage, and dedication live on every day.

Y EARS BEFORE ALCOHOLISM destroyed my father, when I was still a small child, I would roar and meow and quack and moo. He would film me while I got on my hands and knees and pretended to be a dog or beat my chest like a monkey or puckered my lips like a fish. I wanted to be Jane Goodall when I grew up. Near my bed, I kept a picture of her touching the fingertips of a chimp. On my shelves, I kept all her books. No one called me crazy.

I knew, with that childlike clarity that doesnt consider what makes sense, that I was destined to spend a lot of time with animals and that this would make me live happily well past the ever after. I never dreamed of growing up to become a rock-bottom bulimic, a person swallowed by a ceaseless desire to fill up and get empty.

But I suppose the only future in a childs dream is a good one.

When I first stuck my hands down my throat at seventeen, I wanted to lose some weight. Animals couldnt make the guys I liked like me back. Animals couldnt make me fit in with the popular girls. Animals couldnt keep my father sober. Animals couldnt give me the things I needed to be okay.

I believed power and love accompanied a thinner body.

But the things you believe can be a choke chain. They can steal from your dreams, your dignity, your ability to care for yourself and others.

What you believe can steal your life.

WHEN I WAS eighteen, I participated in a homemade bikini contest in Springfield, Massachusetts, dead sober, at a club called, ironically, the Hippodrome. My best friend, Chloe, was doing this contest and in my eyes, she had the perfect body, the perfect face, the perfect style. I wanted to be just like her. So I didnt flinch when a middle-aged woman with huge breasts in a tube top asked me to sign up, too.

The emcee introduced Chloe as One Yummy Treat and she strutted onstage in front of a crowd of a hundred clubgoers, with just a few Reeses Peanut Butter Cup wrappers taped to her naked body. She slathered herself in whipped cream, squatted, and smacked the floor with her hands. When the audience went wild, a panic came over me. I was wearing two cupcake wrappers taped over my nipples and one over my crotch, nothing covering my ass. My legs, freshly shaven and doused in oil to make them glisten under the spotlight, wouldnt move.

Birthday Surprise, the emcee called, and a black girl dressed in every color of the rainbow tapped me on the shoulder and said, Youre up.

The stage vibrated beneath my feet while speakers boomed Juveniles Back That Azz Up. Pink and blue lights beamed like lasers around the room, and the crowd whistled and hooted. The louder the crowd became, the more the rush of feeling desired exhilarated me, the more I grinded and shook my ass.

I came in second. I beat the girl who wore just a garden hose over her body and a sunflower in her hair. I beat the one covered in liquefied chocolate. I beat the rainbow girl, too, and I was thrilled. I went back to the prop room beaming with pride. Looking good, without a doubt, was worth it.

The prop room was small and dimly lit, filled with piles of fake flowers, glitter, whipped cream cans, and pinwheels. While I unpeeled the cupcake wrappers from my body to get dressed, a colony of black ants swarmed around some cake crumbs in the corner of the room. Other girls took shots, put their six-inch heels back on. I watched a dozen inky black specks trek in single file with cake crumbs on their backs. They disappeared and reemerged from a small hole in the wall, focused only on their mission, clueless about their fragility, how they could drown in a wad of spit or be smashed by a finger in two seconds.

Where were the ants putting these crumbs? Why were they always in search of more?

WHEN I THINK back to the girl in that prop room, I wish I could tell her to find stable ground, to stay away from anything that told her the size of her body mattered, whether in a magazine or in a crowd of throbbing dicks and clapping hands at the Hippodrome or anywhere in the known world. I wish I could tell her to stay close to the things she loved. Find joy, I would say. Feel alive!

But I didnt know how. My father drowned in seas of vodka and denial. I stuck my fingers down my throat and reached all the way to my heart, trying to yank it out. I didnt know that the dark hole in my life wasnt in some wall but was instead deep inside me, an endless urge for more. I didnt know that in five years I would be hospitalized and living in a rehab center with women who were too thin to walk, only allowing themselves to eat things like computer paper and miniature carrots. I didnt know that I would wake up with raw knuckles, bloodshot eyes, and the feeling that my throat was on fire, and that would be normal. For eight years, I grew sicker and sicker until I was vomiting up to twenty times a night.

Every morning, I believed I could make a choice to be sane around food and eat like a normal person. I believed I could make a choice not to lie or hurt the people I loved. I vowed to do better, for my mother, for my sister, for myself, but by noon, those promises were in the toilet. My whole life was.

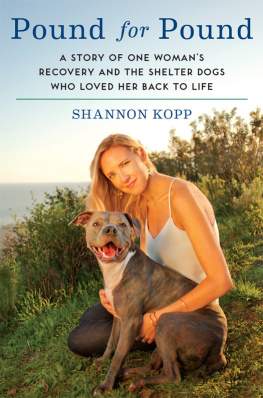

NOT LONG AGO, on a Saturday morning, I volunteered at a local animal shelter. I brought a black pit bull to the play yard behind the shelter, which wasnt really a play yard but a slab of urine-stained concrete surrounded by pebbles and bushes. The dog didnt have a name since she came in as a stray, but I named her Midnight.

Her rear wagged so forcefully that it moved her lower half from side to side. I opened the back door and unleashed her into the yard, and she took off in a full sprint. She rocketed from one end of the small space to the other, galloping back and forth and sometimes leaping into the air. Joy radiated from every ounce of her muscular body. She was a force of wild energy, an intensity of aliveness.