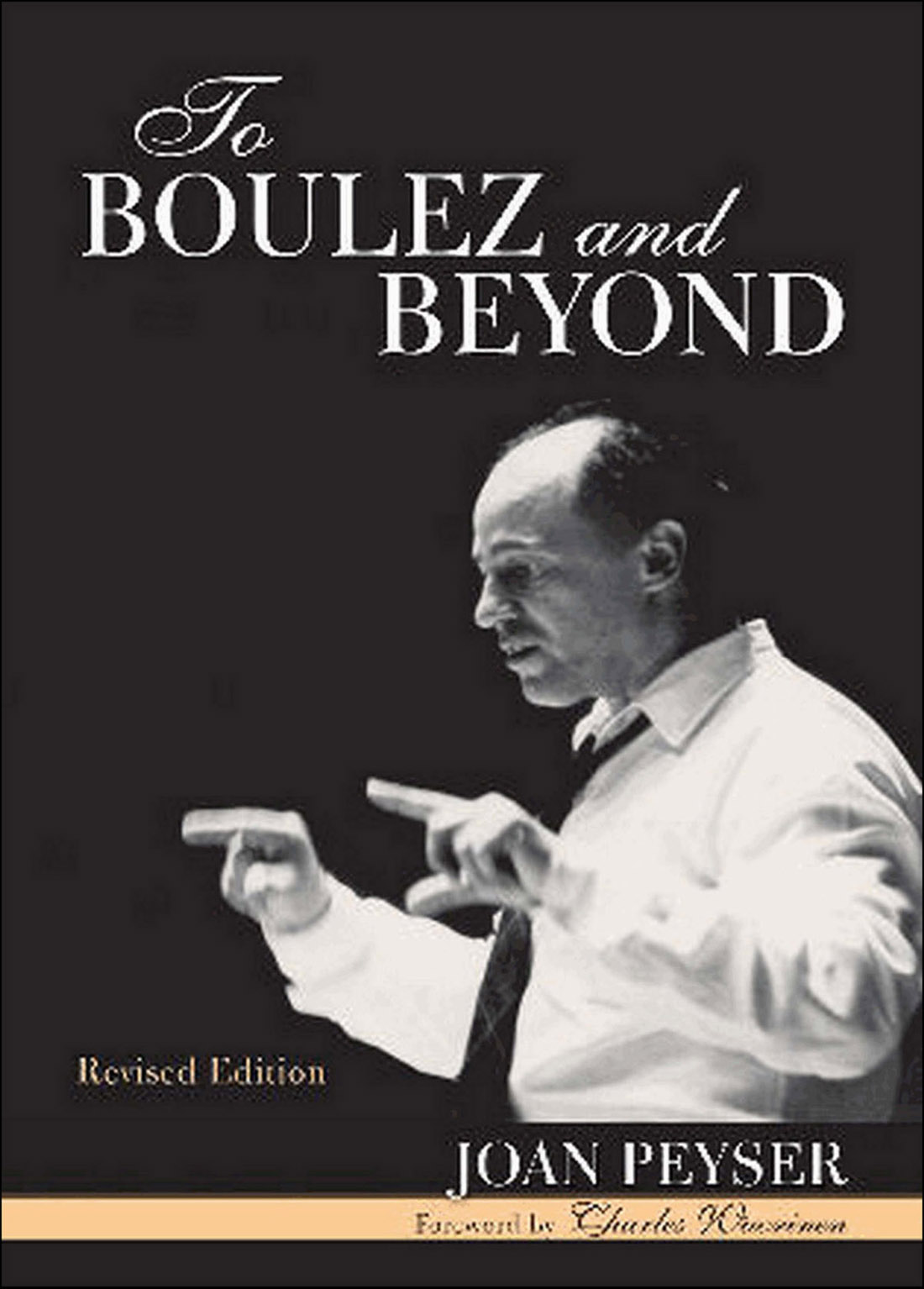

About the Author

Joan Peyser is a musicologist, author, editor and journalist. The winner of six ASCAP/Deems Taylor awards for excellence in writing on music, she became the editor of The Musical Quarterly in 1977 and remained in that post until 1984. Peyser also served as the editor of The Orchestra: Origins and Transformations, which received the award for outstanding book in the humanities category/professional and scholarly publishing division of the Association of American Publishers, 1986.

Born in New York City, Joan Peyser began to play the piano at five, performed in New York's Town Hall at thirteen, majored in music at Barnard College and studied musicology at Columbia University under Paul Henry Lang. She contributed more than sixty articles to the Sunday New York Times, both for its Arts & Leisure section and The Book Review, and her articles have appeared in a variety of intellectual journals: Commentary, The American Scholar, and The Columbia University Forum, as well as in music magazines such as Opera News, Symphony Magazine, Hi-Fi Stereo Review, and the American Record Guide. About the same time, she began to write books: The New Music: The Sense Behind the Sound; Boulez: Composer, Conductor, Enigma; Bernstein: A Biography; The Memory of All That: The Life of George Gershwin; The Music of My Time; and To Boulez and Beyond: Music in Europe Since The Rite of Spring.

Peyser was co-chair of New York University's distinguished Biography Seminar in the late 1980s.

Acknowledgments

T his book originated as two other books I wrote decades ago. The first, The New Music: The Sense Behind the Sound, describes the lives and works of Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky and Edgard Varse. Delacorte published it in 1971. In the present volume, the essence of that material appears in chapters 1 through 17. Schirmer Books/Macmillan published the other, Boulez: Composer, Conductor, Enigma, in 1976, about eighteen months before Pierre Boulez completed his tenure as music director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Occasionally some overlapping occurs. I have edited these books and added chapter 44, which tells what happened between 1976 and 1998. I have also added an afterword in which I briefly describe some first-rate Americans involved in the progressive movement whom I do not include in the body of this mostly European story.

In the spring of 1969, during my first interview with Boulez for the Arts & Leisure section of the Sunday New York Times, the composer-conductor said, I have no confidence in those who think they know their goals. You discover your goal as you come upon it. It's out there in front of you; you discover it each day.

Today I understand what he meant more than I did when he made the statement. For it was not until recently I knew my goal was to write compelling histories of the music of my time. Surely I had no sense of this as a goal when, as a child, I was immersed in the music of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms. From the age of five, I practiced the piano every day under the supervision of my mother, a good amateur musician, who helped me prepare for my weekly lessons. Just before I turned thirteen, I played in a recital in New York's Town Hall and just after, I entered the High School of Music and Art, where I chose viola as my second instrument and played in the school orchestras.

Between my twelfth and fifteenth birthdays, four people close to me died: my piano teacher, my two viola teachers, and my mother, whose illness lasted only six weeks. Virtually everyone who taught me music died.

Excising music from my life, I stopped all lessons and left Music and Art. My first two years at Smith College were as devoid of music as my last two years in a private high school. But then, at the start of my junior year, I married, transferred to Barnard College, and reentered my old world. The new route was an academic one. I majored in music, taking courses in harmony, theory, counterpoint, and history.

I went to graduate school at Columbia University, committing myself to musicology under Paul Henry Lang, a distinguished scholar born in Hungary, educated at the Sorbonne, and instrumental in bringing this European discipline to the United States. Lang presided over the International Musicological Society, was then the editor of The Musical Quarterly, and was the author of a monumental book, Music in Western Civilization. Both in his book and in seminar, Lang shifted the emphasis away from the traditional approachexamining the details within a scoreand towards a view of music in the context of cultural history.

I enthusiastically embraced that approach, but I wanted to do something more. I wanted to consider the individual composer's life. Did Mozart compose differently in 1780 than he did in 1770 because of sociological or aesthetic developments? Or did something happen in his own life? Or both?

What happens matters. I knew this only too well from my own experience, and although I never spoke about that to Lang, I continued to press for a more psychological way of approaching history. All of this took place in the 1950s, more than twenty-five years before the burgeoning of the full disclosure biography that swept American publishing in the 1980s and 1990s.

Lang did not subscribe to my idea. So although I submitted pieces on music to small magazinesall of which were publishedI had not then made any use at all of what I thought necessary to a full understanding of how a work of art was made. Lang's influence was too strong to permit me to do that.

Several years after I left Columbia, I received a commission to write an article on American music at mid-century. At the time Marc Blitzstein, an American composer, had just been killed in a fight in a bar on Martinique. I knew Blitzstein. We had worked together in an American opera program at the New York City Opera and we were neighbors on lower Fifth Avenue. I wanted to write something to help keep his name alive and decided to base my essay on him.

Here was an opportunity to articulate connections between life and work, to deal with external and internal conflicts, to try to understand why this immensely talented and attractive artist, sponsored by the Ford Foundation to compose an opera for the Metropolitan Opera, left a partially completed score in the trunk of a car he stored in Westchester County rather than do what he told everyone he would do: complete it during his stay on Martinique. In telling his story, I would also be able to reveal the effect on him of the then current relationship between Europe and the United States, between capitalism and communism, between his years of study with Schoenberg and his subsequent commitment to socialist realism, between 12-tone music and tonality.

Published in The Columbia University Forum, the essay launched my career. It received the first ASCAP/Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing on music, brought forth a commission from Delacorte, the hardcover division of Dell Publishing Co., for a work on twentieth-century music, and prompted Seymour Peck, then the editor of the Arts & Leisure section of the Times, to ask me to write regularly. I organized the book for Delacorte the same way I had organized the American music essaythrough significant composers.

I chose Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Varse, from the Austro-German, Franco-Russian, French and Greenwich Village domainsand revealed how each of them evolved and affected the others' major moves.

The reader may well wonder why, with a childhood immersed in and limited to old music, music composed no later than Debussy, Satie, and early Stravinsky, I came to concentrate on the new. To understand this requires an acceptance of a mysterious passage from self to symbol. It requires an intuitive sense of why, having experienced what I did in my early teens, I came to equate old (classical) music with death and new (Schoenberg and his followers) with vigor and life.

Next page