VASILY SEMYONOVICH GROSSMAN (19051964) was born into a Jewish family in Berdichev, Ukraine. In 1934 he published both In the Town of Berdicheva short story that won him immediate acclaimand the novel Glyukauf, about Donbass miners. During the Second World War, he worked as a reporter for the army newspaper Red Star; his vivid yet sober The Hell of Treblinka (1944), one of the first articles in any language about a Nazi death camp, was used as testimony in the Nuremberg trials. Stalingrad was published to great acclaim in 1952 and then fiercely attacked. A new wave of purges was about to begin; but for Stalins death in 1953, Grossman would likely have been arrested. During the next few years Grossman, while enjoying public success, worked on his two masterpieces: Life and Fate and Everything Flows. The KGB confiscated the manuscript of Life and Fate in February 1961. Grossman was able, however, to continue working on Everything Flows, a novel even more critical of Soviet society than Life and Fate, until his last days. He died on September 14, 1964, on the eve of the twenty-third anniversary of the massacre of the Jews of Berdichev in which his mother had died.

ROBERT CHANDLER s translations from Russian include works by Alexander Pushkin, Teffi, and Andrey Platonov. He has also written a short biography of Pushkin and has edited three anthologies of Russian literature for Penguin Classics. He runs a monthly translation workshop at Pushkin House in London.

ELIZABETH CHANDLER is a co-translator, with her husband, of Pushkins The Captains Daughter; of Vasily Grossmans Everything Flows and The Road; and of several works by Andrey Platonov.

YURY BIT-YUNAN completed his doctorate on the work of Vasily Grossman. He now lectures on literary history and criticism, while continuing to research Grossmans life and work.

OTHER BOOKS BY VASILY GROSSMAN PUBLISHED BY NYRB CLASSICS

An Armenian Sketchbook

Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler

Introduction by Robert Chandler and Yury Bit-Yunan

Everything Flows

Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler and Anna Aslanyan

Introduction by Robert Chandler

Life and Fate

Translated and with an introduction by Robert Chandler

The Road

Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler and Olga Mukovnikova

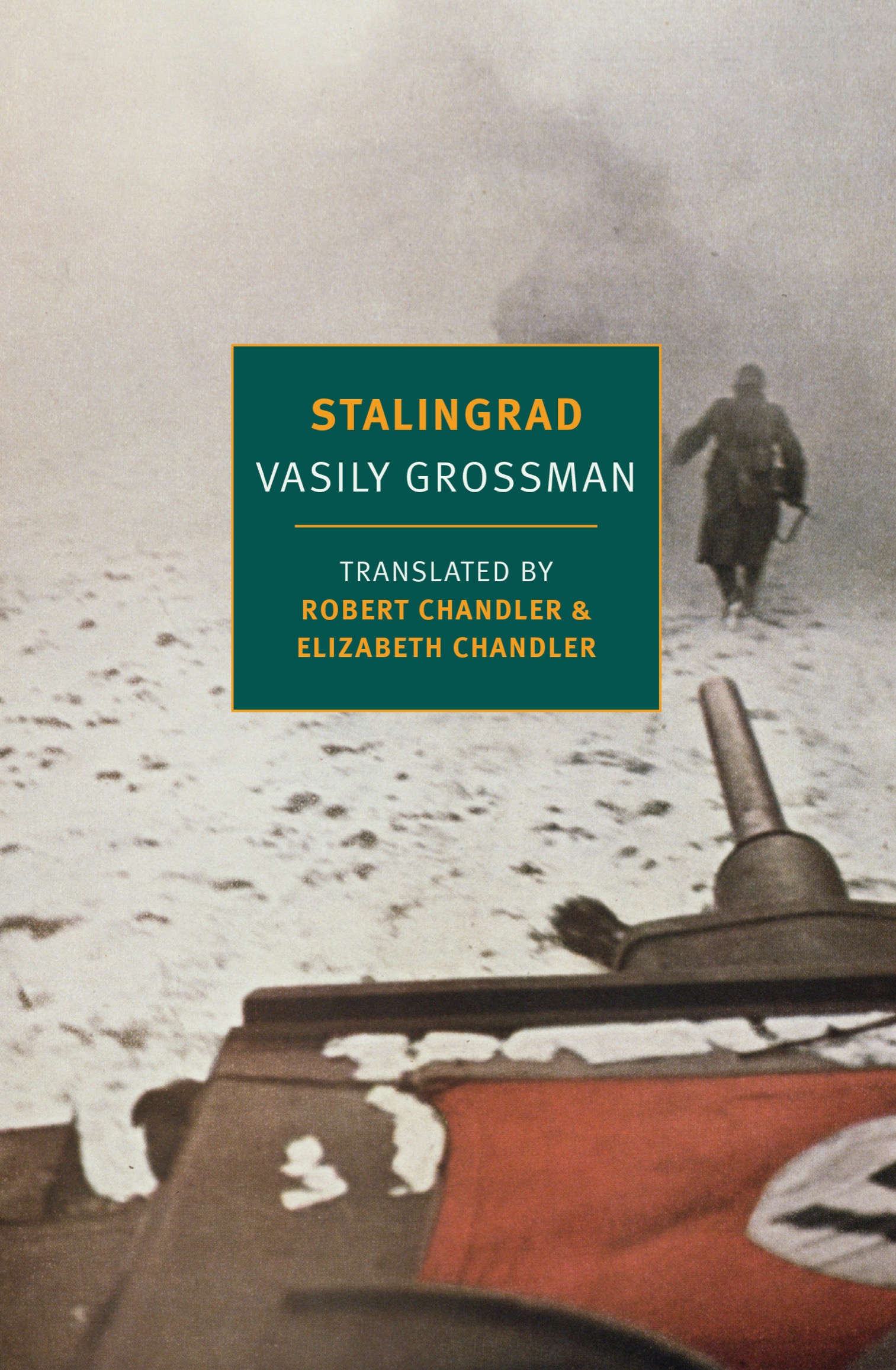

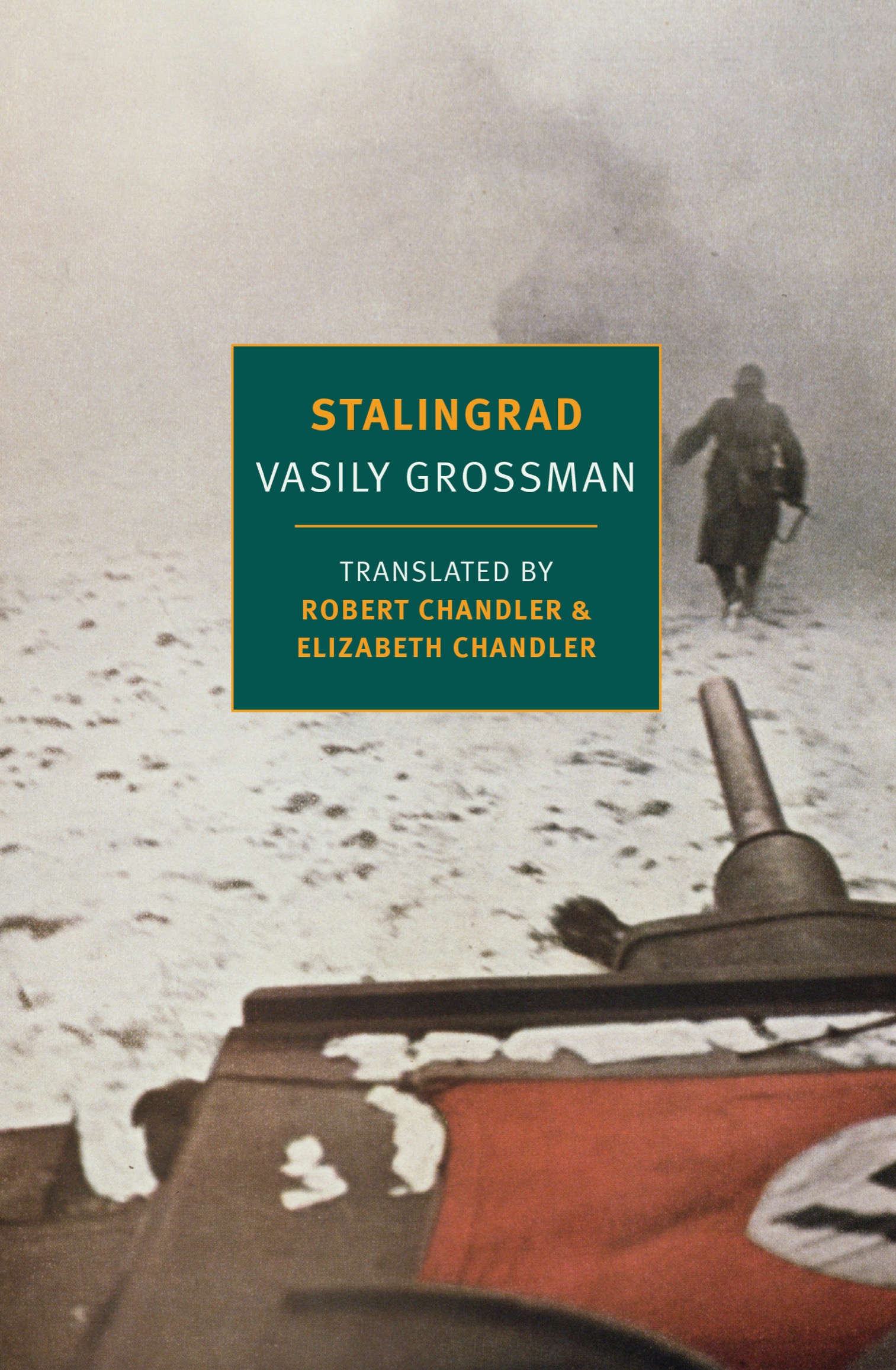

STALINGRAD

VASILY GROSSMAN

Translated from the Russian by

ROBERT CHANDLER

and ELIZABETH CHANDLER

Edited by

ROBERT CHANDLER

and YURY BIT-YUNAN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright by Ekaterina Vasilievna Korotkova and Elena Fedorovna Kozhichkina English translation 2019 by Robert Chandler

Introduction, notes, and afterword 2019 by Robert Chandler

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Arthur Grimm, German Troops Advancing on Stalingrad, first published in Signal magazine, January 1942; private collection/Bridgeman Images Cover design: Katy Homans

The publication was effected under the auspices of the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation TRANSCRIPT program to support translations of Russian Literature

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Grossman, Vasili, author. | Chandler, Robert, 1953 translator.

Title: Stalingrad / by Vasily Grossman ; translated by Robert Chandler.

Other titles: Za pravoe delo. English

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2019] | Series: New York Review Books classics | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018036773 (print) | LCCN 2018059214 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681373287 (epub) | ISBN 9781681373270 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Stalingrad, Battle of, Volgograd, Russia, 19421943Fiction. | Soviet UnionHistoryGerman occupation, 19411944Fiction.

Classification: LCC PG3476.G7 (ebook) | LCC PG3476.G7 Z2313 2019 (print) | DDC 891.73/42dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018036773

ISBN 978-1-68137-328-7

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

War and Peace , The Black Book , and the Many Versions of Stalingrad

With a weary smile [Marshal Timoshenko] went on, Names, nameshow many times must I say this? You must know your mens names! Turning to Novikov, he asked, Do you know his name, Colonel?

Novikov named the man who had died: Lieutenant Colonel Alferov.

Memory eternal! said Timoshenko.

V ASILY Grossmans Life and Fate has been hailed as a twentieth-century War and Peace. It has been translated into most European languages, and also into Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Turkish, and Vietnamese. There have been stage productions, TV series, and an eight-hour BBC radio dramatization. Most readers, however, have been unaware that Grossman did not originally conceive of Life and Fate as a self-contained novel. It is, rather, the second of two closely related novels about the Battle of Stalingrad, which it is probably simplest to refer to as a dilogy. The first of these two novels was first published in 1952, in a heavily censored edition and under the title For a Just Cause. Grossman, however, had wanted to call it Stalingradand that is how we have titled it in this translation.

The characters in the two novels are largely the same and so is the story line; Life and Fate picks up where Stalingrad ends, in late September 1942. Ikonnikovs essay on senseless kindnessnow a part of Life and Fate and often seen as central to itwas originally a part of Stalingrad. Another of the most memorable elements of Life and Fatethe letter written by Viktor Shtrums mother about her last days in the Berdichev ghettois of central importance to both novels. The actual words of the letter were probably always intended for Life and Fate, but it is in Stalingrad that Grossman tells us how the letter reached Viktor and what he felt when he read it.

Grossman completed Life and Fate almost fifteen years after he first started work on Stalingrad. It is, amongst other things, a considered statement of his moral and political philosophya meditation on the nature of totalitarianism, the danger presented by even the most seemingly benign of ideologies, and the moral responsibility of each individual for his own actions. It is this philosophical depth that has led many readers to speak of the novel as having changed their lives. Stalingrad, in contrast, is less philosophical, but more immediate; it presents us with a richer, more varied human story.

Grossman worked as a front-line war correspondent throughout nearly all the four years of the SovietGerman war. He had a powerful memory and an unusual ability to get people from every walk of life to talk openly to him; he also had relatively free access, during the war years, to a wealth of military reports. His wartime notebooks include potted biographies of hundreds of individuals, scraps of dialogue, and sudden insights and unexpected observations of all kinds. Much of this material found its way into