About the Author

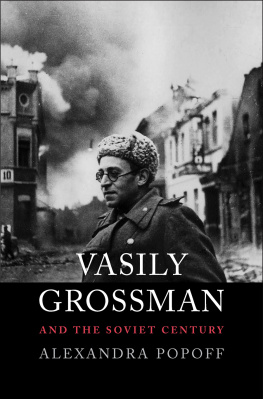

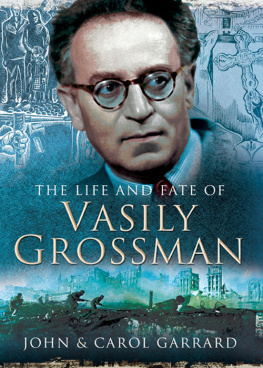

Vasily Grossman was born in 1905. In 1941 he became a correspondent for the Red Army newspaper, Red Star, reporting on the defence of Stalingrad, the fall of Berlin and the consequences of the Holocaust, work collected in A Writer at War. In 1960 Grossman completed his masterpiece Life and Fate and submitted it to an official literary journal. The KGB confiscated the novel and Grossman was told that there was no chance of it being published for another 200 years. Eventually, however, with the help of Andrey Sakharov, a copy of the manuscript was microfilmed and smuggled out to the west by a leading dissident writer, Vladimir Voinovich. Grossman began Everything Flows in 1955 and was still working on it during his last days in hospital in September 1964.

Linda Grant was born in Liverpool on 15 February 1951, the child of Russian and Polish Jewish immigrants. She is the author of Sexing the Millennium: A Political History of the Sexual Revolution, The Cast Iron Shore, Remind Me Who I am Again, Still Here, The People On The Street: A Writers View of Israel, The Clothes On Their Backs, The Thoughtful Dresser and We Had It So Good. Her second novel, When I Lived in Modern Times, set in Tel Aviv in the last years of the British Mandate, won the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2000.

For more information on Orange Inheritance editions please see www.orange.co.uk/bookclub

Also by Vasily Grossman

Everything Flows

Introduction by Linda Grant

In the summer of 2003 I read Vasily Grossmans Life and Fate. It took three weeks to read and three weeks to recover from the experience. Novels fade, your immersion in their world turns into a faint dream, and then is forgotten. Only great literature grows in the imagination. Grossmans book did more than grow, it seemed to replace everything I had previously thought and felt, filling me with what Grossman calls the furious joy of life itself which I have never lost.

Life and Fate is about the terrible years of the mid-twentieth century in the Soviet Union. Its vast canvas covers the Battle of Stalingrad, the Gulag, the coercion of a state which decides as diktat the nature of reality and of truth, however preposterously distant from actual reality and truth. Generals on the Front, common soldiers, mothers, wives, sons, daughters, sisters, ex-husbands, a boy about to advance on his first kiss, Nazi camp commandant, a prison interrogator, a holy fool, scientists in a Moscow laboratory all of these characters swarm through the pages. Great ideas are discussed: the nature of totalitarianism, the betrayal of the Bolshevik revolution, the nature of anti-Semitism, military strategy, the question of freedom and how we can be free despite the external circumstances that chain us.

Life and Fate can be a daunting, monumental read. But its greatness is not the weight of those themes, for at the end of its 871 pages you are left with a message which, to the reader just starting the novel, might appear so banal that it could be inscribed on a greetings card. For Grossman, communism and fascism are ephemera. What matters, what endures, is the individual and the ordinary act of human kindness, indeed the often senseless act of kindness, as when an old Russian woman, about to hoist a brick in the face of a captured German soldier, instead finds to her own incomprehension that she has reached into her pocket and given him a piece of bread. And in the years to come, will still never be able to understand why she did it.

Grossman was not opposing ideology with Christian forgiveness, far from it. He was a Soviet Jew whose Jewishness became more and more meaningful to him as he was caught between the vast threats of anti-Semitism both from Nazi Germany and at home in the form of the increasingly deranged conspiracy theories of Stalin. The passion of Life and Fate is not for ideas or history, but for the ordinary; for human life in all its perplexing, muddled, contradictory and infuriating variety. Grossman takes us into the minds of a group of soldiers waiting in the forest: one is full of dire forebodings, one is singing, one is chewing bread and sausage and thinking about the sausage, one is trying to identify a bird, one worries about whether hed offended his friend, one is composing a farewell poem to autumn, one is remembering a girls breasts, one is missing his dog. This passage leads to the substance of Grossmans central thought, which at the time he was writing could lead to the arrest of a Soviet citizen: The only true and lasting meaning of the struggle for life lies in the individual, in his modest peculiarities, and his right to these peculiarities.

Such treasonous ideas can topple empires.

In the weeks after I first read Life and Fate I was desperate to talk about it, and found a tragic absence. No one I knew had read the novel. Almost no one had even heard of it. The early years of the last decade were the time when Life and Fate and its author were only just beginning to be discovered by English-language readers, following the Harvill Secker publication of Robert Chandlers translation. These early awakenings of interest were largely due to the publication of two best-selling books, Stalingrad and Berlin: The Downfall by the military historian Antony Beevor, who drew heavily on Grossmans journalism as source material. Grossman spent the war as a correspondent, he was there at the Battle of Stalingrad and is believed to have been the first reporter of any nationality to enter the extermination camp of Treblinka and make speakable the horrors he found there.

It was ironic that a former British army officer should lead me directly to one of the greatest European Jewish writers of the century, in a field dominated by Proust, Kafka, Isaac Babel, Bruno Schulz and Joseph Roth.

Life and Fate affected me like no other novel. It affected me personally. The danger in describing this impact is that it will sound to new readers as if Grossman is a writer with a message, and messages tend to kill art stone-dead. Grossman did, of course, have something to say, but its purpose was against the whole notion of the Big Idea. Whatever Grossman was up to, he was not trying to recruit anyone; instead, he was telling us to leave each other alone, to stop harming each other with our insistence on telling others what to think and how to live.

Yet Grossman changed me. The compassion of Kafka for his commercial traveller trapped in the body of an insect, the historic scope of Joseph Roth and Isaac Babels hard-headed understanding of war, were all elements of an impact that it is difficult to describe, even years later. I had written novels about idealists, all failed, but political idealism still seemed worth the effort. Idealism is a romantic pursuit, it speaks to the heart, it flatters our egos. Grossman, no reactionary, taught me that the right to our own modest peculiarities is the only right worth fighting for. In his novel there are no heroes, no saints and no supermen. This must have seemed an extraordinarily dangerous message in the Soviet Union of the early Sixties, despite the Khrushchev thaw.

Life and Fate, unlike the work of the Soviet Unions other internationally-recognised dissident writers, Boris Pasternak and Alexander Solzhenitsyn, was virtually unknown in the West until the mid-Eighties because the year after its completion in 1960 the book was, in the authors words, arrested. KGB men came to Grossmans flat, removed all copies, removed carbon paper and even the ribbon from his typewriter in case it had left a tell tale imprint. He was told that if his book were ever published, it would not be for another two hundred years. The Soviet Union was careful not to make a martyr of him and he continued to publish stories in important journals in the remaining few years of his life. But there were no Nobel Prizes or committees abroad campaigning for his safety, and part of the torment of his final years was the belief that his lifes work would become, in the word he used to describe the prisoners in Stalins camps, dust: a forgotten book about times everyone wanted to forget.