VASILY GROSSMAN

Vasily Grossman

A Writers Freedom

Edited by

ANNA BONOLA and

GIOVANNI MADDALENA

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2018

ISBN 978-0-7735-5447-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5448-1 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5540-2 (e PDF )

ISBN 978-0-7735-5541-9 (e PUB )

Legal deposit third quarter 2018

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free

(100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Universit

Cattolica del Sacro Cuore and from the Vasily Grossman Study Center

(Turin, Italy).

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which

last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout

the country.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. Lan dernier,

le Conseil a investi 153 millions de dollars pour mettre de lart dans la vie

des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Vasily Grossman: a writers freedom / edited by Anna Bonola

and Giovanni Maddalena.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-7735-5447-4 (hardcover). ISBN 978-0-7735-5448-1 (softcover) .

ISBN 978-0-7735-5540-2 (e PDF ). ISBN 978-0-7735-5541-9 (e PUB )

1. Grossman, Vasili I Semenovich Criticism and interpretation. 2. Russian

literature 20th century History and criticism. I. Bonola, Anna, editor

II. Maddalena, Giovanni, 1971, editor

PG 3476. G Z 92 2018 891.73 ' C 2018-901930-1

C 2018-901931- X

This book was typeset by Marquis Interscript.

Contents

Note on Transliteration

Different scholars and translators use different systems of transliteration. We generally use a modified version of the Library of Congress system of transliteration, except in quotations, references, and the bibliographies, where we keep the choices of others.

The single and double apostophes that represent the Russian soft and hard signs have been deleted to ease reading, and t he following C yrillic letters are transliterated in this way: ( e , ye only initially and after a vowel), ( yo ), ( zh ), ( z ), ( y ), ( kh ), ( ch ), ( ts ), ( sh ), ( shch ), ( y ), ( e ), ( yu ) , ( ya ).

For well-known names such as Dostoevsky, Vasily Grossman, Khrushchev, etc., we have used the more popular spellings.

VASILY GROSSMAN

Introduction

ANNA BONOLA AND GIOVANNI MADDALENA

The fame of an author does not always fully correspond, quite rightly, to his actual importance and his real position in the world of literature. Time is an implacable judge of unmerited literary fame. However, time is not the enemy of genuine literary value; on the contrary, it is a good and reasonable friend, as well as a serene and loyal custodian.

Grossman 1960

These are the words that Vasily Grossman (19051964) used when talking about his friend Andrey Platonov, the great writer who was only published with difficulty during the Soviet period. his books have for the most part only been studied and translated within the last twenty years. In this book, we present some of the most recent essays dedicated to the work of one of the greatest prose writers of the Russian twentieth century. The aim of this collection is to unfold some of the most crucial aspects of Grossmans work to an English-speaking public.

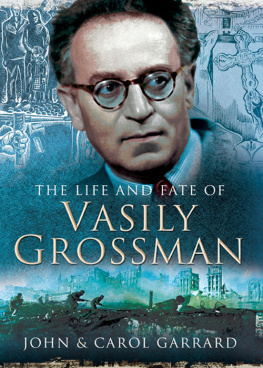

For a detailed portrait of Grossmans life we refer to the seminal biography written by John and Carol Garrard, The Life and Fate of Vasily Grossman (2012). However, a few words of introduction, and a brief sketch of his life, will illustrate the complexity of Grossmans story. On the one hand, he was a Soviet writer, not only from a chronological point of view (he wrote from 1928 to 1964), but also in style and subject matter, at least until the 1950s; on the other hand, he eventually appeared in the West as the leading authentic dissident of Russian literature ( Markish 1983, 9 ). Maurizia Calusio, author of one of the essays in this collection, explains the paradox this way:

Both the dissident Grossman of Life and Fate and Everything Flows and the author of the striking, late short stories remained virtually ignored for years after his death. On the one hand there was the dull official Party literature of the time, and on the other the clandestine literature, accessible through the Samizdat and Tamizdat.

Vasily Grossman was born in 1905 to a well-off Jewish family in the town of Berdichev, where he grew up and studied during the political and social upheaval that preceded the Russian Revolution (1917). During the years of civil war (191722), years of famine, he moved to Kiev with his mother in order to keep up with his studies. In 1923, he went to Moscow to study chemistry at the university, but at the same time, he cultivated his interest in literature. With the help of his mothers cousin Nadya Almaz, he began his literary career in the Soviet capital. In 1929, he signed his first contract with the journal Ogonek to write a tale about his hometown, Berdichev. In 1929 he married his former schoolmate Anna Petrovna Matsuk. They divorced a short time later (1932), but in 1930 they had Grossmans only child, Yekaterina, who grew up with Grossmans mother in Ukraine. In 1933 the Soviet secret police ( OGPU ) arrested Nadya Almaz and charged her with Trotskiyism. She was condemned first to exile and afterward to a prison camp, but his association with Nadya Almaz did not delay the development of Grossmans career, and he started to become popular around 193435. Maksim Gorkiy, the master of Soviet literature, arranged the publication of Grossmans novel Glyukauf . In 1934 Grossman published Schaste ( Happiness ) and in 1936 Chetyre Dnya ( Four Days ), two collections of short stories. Besides his literary successes, he started a new chapter in his personal life. In 1935, he fell in love with Olga Mikhailovna Guber, the wife of one of his friends and a mother of two children, and they were married in 1936. In 1937, Olga Mikhailovnas former husband was executed, and in 1938 Olga was arrested. Showing great courage, Grossman adopted her children to save them from the camps and voluntarily underwent interrogation by the police in order to defend his wife. He also wrote to Ezhov, the head of the NKVD (the political police apparatus), asking him to intercede for her. Eventually, Olga was set free.

During the Second World War, Grossman enlisted in the Red Army as a war correspondent, writing a series of war reports for the Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda , which Soviet readers consumed eagerly. In 1942, he published a war novel, The People Immortal , inspired by his experience at the front, which was translated and published in English the next year.

In the first essay in this collection, John and Carol Garrard describe Grossmans writing on the Battle of Stalingrad, where the Soviet comeback against the Nazis began. This battle was a turning point in Grossmans life. Grossman describes it in its most concrete details, but despite the horrors, he wrote in a letter to his father: I have no desire to leave here. Even though the situation has improved, I still want to stay in a place where I witnessed the worst times ( Garrard and Garrard 1996, 159 ). Stalingrad was for Grossman a liberating experience of making contact with common people. For one hundred days, he was allowed to move in the zone along the west bank of the Volga river, the most dangerous zone in the battle, from which the officers of the Party had fled. As a result, Grossman became more and more aware of the nature and forms of totalitarian coercion in the Soviet Union, and he could compare the two totalitarianisms that he was observing in their fatal clash.