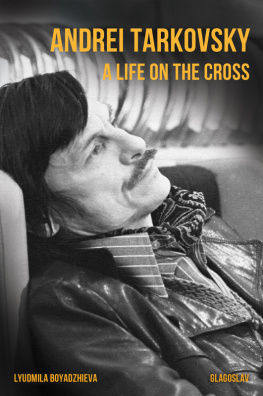

ANDREI TARKOVSKY

A LIFE ON THE CROSS

ANDREI TARKOVSKY:

A LIFE ON THE CROSS

by Lyudmila Boyadzhieva

Translated by Christopher Culver

Edited by Scott D. Moss and Camilla Stein

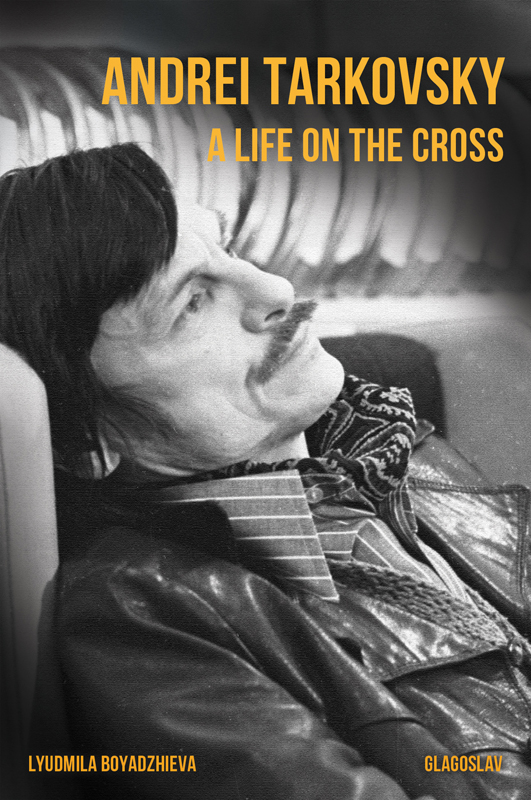

Image courtesy of Kai holland, akg-images Gmbh

2012, Alpina Non-fiction

2014, Glagoslav Publications, United Kingdom

Glagoslav Publications Ltd

88-90 hatton Garden

EC1N 8PN London

United Kingdom

www.glagoslav.com

ISBN: 978-1-78267-103-9 (EPUB)

ISBN: 978-1-78267-104-6 (MOBI)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book contains content used for illustration or comment in educational institutions during instructional, research, or scholarly activities for educational purposes.

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

LYUDMILA BOYADZHIEVA

ANDREI TARKOVSKY

A LIFE ON THE CROSS

GLAGOSLAV PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

T arkovsky revolutionized the world of filmmaking, working almost half a century ahead of his time.

He brought a kind of magically arranged film content to life, which the audience was not supposed to understand or even perceive. Emotions and the intellect are only pitfalls in an attempt to understand the human soul. He sought a way to convey deep, mysterious but stirring images from one soul to another, he dreamed of a filmmaking that affected people on a subconscious level, because this would save all mankind. He knew one thing for sure: in order to survive, the world needs a renewed Homo sapiens, developing under the influence of great art, high culture and firm spiritual values, an individual driven exclusively by moral standards, ignoring all the material demands of the base flesh.

Cinema, true cinema, would be the unique means of influencing the transformation of the human race and therefore the most effective medium for saving the world.

Andrei Tarkovsky made seven complete films and left one unfinished. Each of them won the highest acclaim from the international film community. One of his films, Andrei Rublev, has been given the title of film of films, just as the Bible has been called the Book of books.

A great deal has been written and said about Tarkovsky. His films have been watched and will continue to be watched, uncovering more and more meanings, sparking reflection and debate, at least as long as the controversy between the spiritual and the material finds no definitive solution; as long as there are no answers to the eternal questions such as: Who are we? Who sent us into this world? What are we living for? Where do we go afterwards? It is only then that what tormented Tarkovsky, gazing into the abyss of human existence, will seem to us, the omniscient ones, no less naive than the historical disputes over the shape of the Earth.

It seems, however, that the plan of the Creator, combining spirit and flesh into a single creation, does not offer any key. Therefore, the search for the meaning of existence, expressed by the language of cinema, will always be relevant, as long as cinema does not become a quaint exoticism, out of touch with the mankind of a new civilization; when, like old floppy disks, communication by means of a camera and the methods of transferring information available to it become superseded with no going back. Only then will the damnable questions, debated for centuries, be approached through other means of creativity.

However, something quite the opposite might happen as well. It may be that the magical, not entirely comprehensible essence of Tarkovskys films will be of particular importance to a world on its way to spiritual collapse. The special properties of his film language are matter, cut open, as if under the dissectors knife, and time caught in a trap by a motionless camera these transform the slow pacing and the unspoken into spiritual zones (like Goa, hidden from civilization), areas for meditative immersion into the depths of self-knowledge, and they will preserve his films in a special niche of wisdom, along with religious teachings and spiritual practices.

Tarkovskys seven-and-a-half films are a drop of something different in the ocean of commercial and simply bad cinema, whatever its origin. These seven-and-a-half achievements, standing apart in the world of film, are like the small verdant island in the mysterious ocean of Solaris and have become a code word for a persons intellectual and aesthetic maturity, a sort of IQ_in and of themselves.

When thinking of Tarkovsky and his work, one main, unanswered question remains, connected to a realm generally inaccessible to human beings: the matter of talent, inspiration, sudden insights, i.e. the presence of some irrational higher power in earthly affairs, in the frail confines of human embodiment, which is often alien to this higher power.

Where did Tarkovsky, not always aware of the workings of his revolutionary output, draw these images, motifs, ways of combining or the joining together of various aspects of creation into a single whole, playing with such concepts as the soul, matter, humanity, history, death and eternity?

He established new worlds out of elements that were occasionally not rationally explainable, studying phenomena and feelings that were not so close to him personally sacrifice, compassion, love. The paradox of Tarkovskys personality, marked by an enigmatic complexity, consists in his simultaneous existence in two different worlds, his double citizenship": the material and the spiritual. Thus in the higher spheres lie the sources of his unique talents, while the mundane level determines ones human nature, something that cannot be confused with talent and often contradicts it. The result of this is the long series of paradoxes which followed all of Tarkovskys undertakings like a bad omen.

He respected his home country, accepting it with all its drawbacks of full-fledged socialism, with its idiocies, cruelty, hypocrisy and hostility. He wanted to be understood by his own country, embraced and rewarded by it. However, being far from political and social engagement, lacking an understanding of the backstage workings of the world of cinema, he suffered failure after failure. For the Soviet authorities, the law-abiding, ideologically moderate Tarkovsky remained an outsider, a nuisance due to his obscurity and incapability for mutual understanding. Sniffing out with their hunters senses his outsider inclinations, the authorities did everything they could to reject his works, excommunicate and annihilate them. Standing distant from ideological rebellion, devoted to his country without any dissident plotting, Tarkovsky virtually became a foreign object, forced to seek refuge abroad.

He thought of himself as a messiah, devoting all his spiritual and creative energy to the refinement of humanity. But the audience for whom he worked often was unable to reach an understanding of what he was preaching. The wide audience of the USSR had no cultural bearings with which to get a handle on Tarkovskys films. They lacked an intellectual background and subtleness of perception, a familiarity with sophisticated material. Yes, my films are received with difficulty, Tarkovsky admitted. But I will not make even the smallest compromise for the masses, make my films more accessible or interesting, I will not take even half a step toward being understood by the audience.