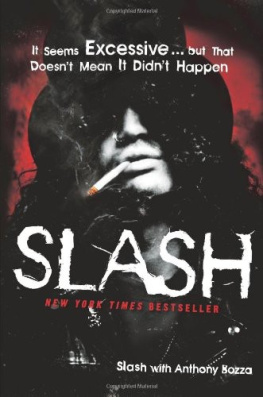

I t felt like a baseball bat to my chest, but one swung from the inside. Clear blue spots lit up the corners of my vision. It was abrupt, bloodless, silent violence. Nothing was visibly broken, nothing had changed to the naked eye, but the pain made my world stand still. I kept playing; I finished the song. The audience didnt know that my heart had done a somersault just before the solo. My body had delivered its karmic retribution; reminding me, onstage, of how many times Id intentionally served it up a similar loop-de-loop.

The jolt quickly became a dull ache that almost felt good. In any case, I felt more alive than I had a moment before, because I was more alive. The machine in my heart had reminded me of just how precious this life is. Its timing was impeccable: with a full house in front of me, while I played my guitar, I got the message loud and clear. I got it a few times that night. And I got it every time I was onstage for the rest of that tour, though I never knew when it was coming.

A doctor installed an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in my heart when I was thirty-five. Its a three-inch-long battery-powered generator that was inserted through an incision in my armpit. It constantly monitors my heart rate, delivering electroshocks whenever my heart beats too dangerously fast or slow. Fifteen years of overdrinking and drug abuse had swollen that organ to one beat short of exploding. When I was finally hospitalized, I was told I had six weeks to live. Its been six years since then and this piece of machinery has saved my life more than a few times. Ive enjoyed a convenient side effect that the doctor did not intend: when my indulgences have caused my heart to beat too dangerously slow, my defibrillator has popped off, keeping death from my door for one more day. It also shocks my heart into submission when it beats fast enough to court cardiac arrest.

Its a good thing I got it adjusted before the first Velvet Revolver tour. I did that one sober for the most part; sober enough that the excitement of playing with a band I believed in to fans who believed in us moved me to my core. I hadnt been that inspired in years. I ran all over the stage; I basked in our collective energy. My heart raced with excitement hard enough to trigger the machine inside me onstage every night. It wasnt pleasant but I began to welcome those reminders. I saw them for what they were. Strange moments of alienated clarity, moments out of time that encapsulated a lifes worth of hard-won wisdom.

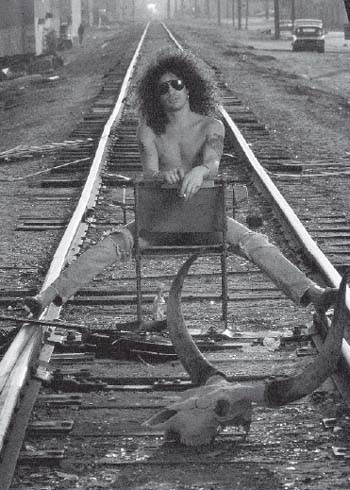

I was born on July 23, 1965, in Stoke-on-Trent, England, the town where Lemmy Kilmister of Motrhead was born twenty years before me. It was the year rock and roll as we know it became greater than the sum of its parts; the year a few isolated bands changed pop music forever. The Beatles released Rubber Soul that year and the Stones released Rolling Stones No. 2 , the best of their collections of blues covers. There was a creative revolution afoot that has never been equaled and Im proud to be a by-product of it.

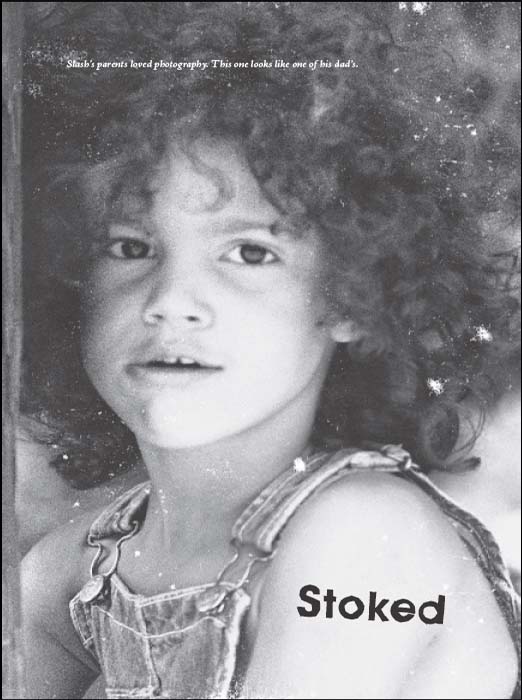

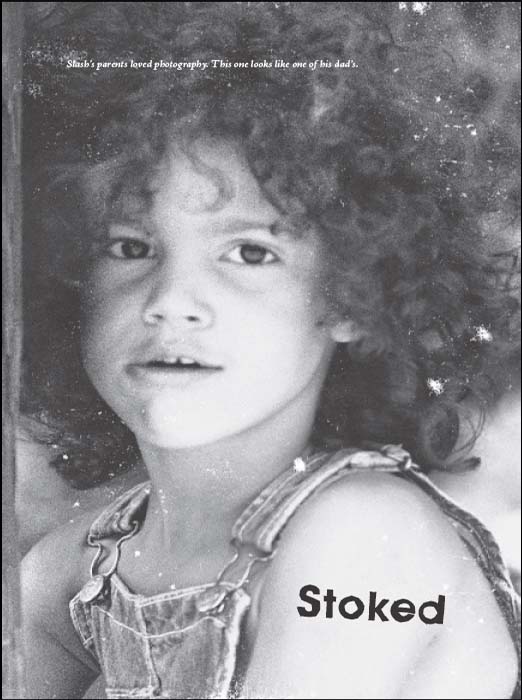

My mom is an African American and my dad is English and white. They met in Paris in the sixties, fell in love, and had me. Their brand of interracial intercontinental communion wasnt the norm; and neither was their boundless creativity. I thank them for being who they are. They exposed me to environments so rich and colorful and unique that what I experienced even while very young made a permanent impression on me. My parents treated me as an equal as soon as I could stand. And they taught me, on the fly, how to deal with whatever came my way in the only type of life Ive ever known.

Tony Hudson and his sons, 1972. Slash looks exactly like his son London here.

M y mom, Ola, was seventeen and my dad, Anthony (Tony), was twenty when they met. He was born a painter, and like painters historically do, he left his stuffy hometown to find himself in Paris. My mom was precocious and exuberant, young and beautiful; shed left Los Angeles to see the world and make connections in fashion. When their journeys intersected they fell in love, then got married in England. And then I came along and they set about creating their life together.

My moms career as a costume designer started around 1966, and over the course of it, her clients included Flip Wilson, Ringo Starr, and John Lennon. She also worked for the Pointer Sisters, Helen Reddy, Linda Ronstadt, and James Taylor. Sylvester was one of her clients, too. He is no longer with us, but he was once a disco artist who was like the gay Sly Stone. He had a great voice and he was a supergood person in my eyes; he gave me a black-and-white rat that I named Mickey. Mickey was a badass. He never flinched when I fed rats to my snakes. He survived a fall from my bedroom window after he was tossed out by my younger brother, and was no worse for the wear when he showed up at our back door three days later. Mickey also survived the accidental removal of a section of his tail when the inner chassis of our sofa bed cut it off, as well as close to a year without food or water. We left him behind by mistake in an apartment that we used as storage space, and when we eventually popped in to pick up some boxes, Mickey came up to me congenially as if Id been gone only a day, as if to say, Hey! Where you been?

Mickey was one of my more memorable pets. There have been many, from my mountain lion, Curtis, to the hundreds of snakes Ive raised. Basically I am a self-taught zookeeper and I definitely relate to the animals Ive lived with better than to most of the humans Ive known. Those animals and I share a point of view that most people forget: at the end of the day life is about survival. Once that lesson is learned, earning the trust of an animal that might eat you in the wild is a defining and rewarding experience.

SOON AFTER I WAS BORN, MY MOTHER returned to L.A. to expand her business and to lay the financial foundation our family was built upon. My dad raised me in England at his parents, Charles and Sybil Hudsons, home for four yearsand it wasnt easy on him. I was a pretty intuitive kid, but I could not discern the depth of the tension there. My dad and his dad, Charles, from what I understand, had less than the best relationship. Tony was the middle of three sons, and he was every bit the middle child upstart. His younger brother, Ian, and his older brother, David, were much more in step with the familys values. My dad went to art school; he was everything his father wasnt. Tony was the sixties; and he stood up for his beliefs as wholeheartedly as his father condemned them. My grandfather Charles was a fireman from Stoke, a community that had somehow skated through history unchanged. Most residents of Stoke never leave; many, like my grandparents, had never ventured the hundred or so miles south to London. Tonys unyielding vision of attending art school and making a living through painting was something Charles could not stomach. Their clash of opinion fueled constant arguments and often led to violent exchanges; Tony claims that Charles beat him senseless on a regular basis for most of his youth.