Contents

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2015 by Claire Harman

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd., Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2015.

www.aaknopf.com

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Knopf Canada and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harman, Claire.

Charlotte Bront : a fiery heart / Claire Harman.First United States edition.

pages ; cm

This is a Borzoi book.

ISBN 978-0-307-96208-9 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-307-96209-6 (eBook) 1. Bront, Charlotte, 18161855. 2. Women authors, English19th centuryBiography. 3. Novelists, English19th centuryBiography. I. Title.

PR 4168. H 27 2015 823.809dc23 [ B ] 2015028359

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Harman, Claire, author

Charlotte Bront : a fiery heart / Claire Harman.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-307-36319-0 eBook ISBN 978-0-307-36321-3

1. Bront, Charlotte, 18161855. 2. Women novelists, English19th centuryBiography. 3. Novelists, English19th centuryBiography. I . Title.

PR 4168. H 273 2016 823.8 C 2015-907652-8

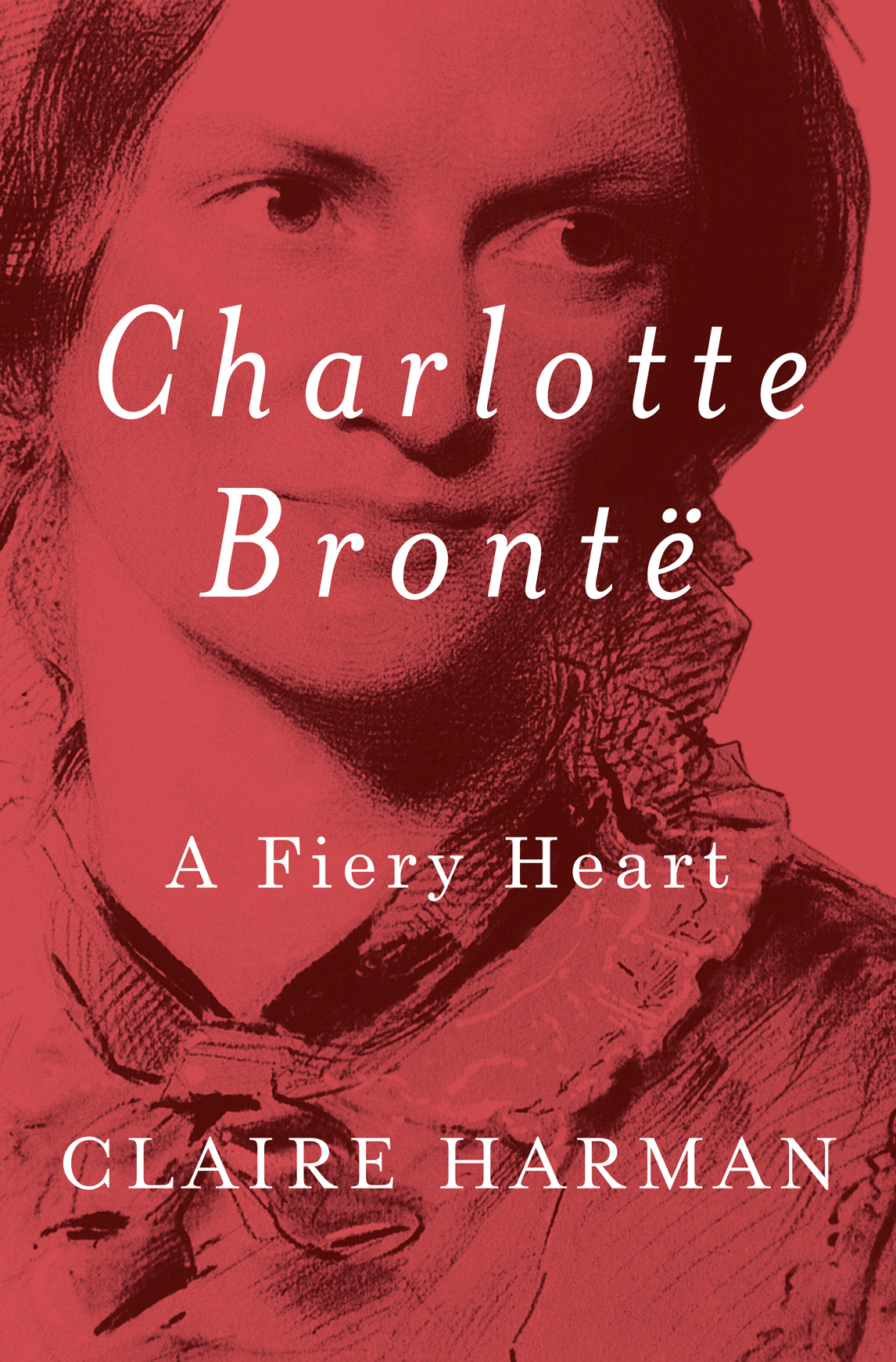

Cover image: Engraving of Charlotte Bront (detail) by Walker & Boutall, after George Richmond.

Interfoto / Alamy

Cover design by Kelly Blair

eBook ISBN9780307962096

v4.1

a

To Paul

theres a fire and fury raging in that little woman a rage scorching her heartShe has had a story and a great grief that has gone badly with her

WILLIAM MAKEPEACE THACKERAY (1852)

a tiny, delicate, little person, whose small hand nevertheless grasped a mighty lever which set all the literary world of that day vibrating

ANNE THACKERAY RITCHIE (1891)

talented people almost always know full well the excellence that is in them

CHARLOTTE BRONT (1846)

Contents

Prologue

1 September 1843

I t is 1 September 1843 and a 27-year-old Englishwoman is alone at the Pensionnat Heger in Brussels, a girls school where she is an unpaid student-teacher. It is halfway through the long vacation and everyone else who has a home or family to go to left weeks ago: the proprietress, Madame Heger, is at the seaside with her husband and children; the other teachers are on holiday or travelling.

Miss Bronts home is too far away to warrant a return for a mere two months. She cant afford the cost of the journey back to her fathers Yorkshire parsonage, and, besides, arrangements should be kept to: Charlotte is a scrupulously dutiful person. But she is finding the empty dormitory oppressive, with all the beds covered in white cloths like a morgue; every meal is eaten alone, and the Pensionnats beautiful garden, with its old fruit trees and alle dfendue of limes, seems more of a prison than a refuge when the rest of the school is abandoned. To escape the heavy solitude, it is Miss Bronts habit to go out and walk the city and the surrounding countryside for hours at a time. I should inevitably fall into the gulf of low spirits if I stayed always by myself here without a human being to speak to, she writes to her sister Emily, who was her companion at the school the previous year and knows the place well. The truth is, although she doesnt tell Emily this, she is already in that gulf. She is desperately unhappy.

Her return to Brussels for a second year at the Pensionnat Heger Charlotte sees with hindsight to have been a terrible mistake, for she has fallen in love with someone who, it is painfully clear, will never see her in a romantic light. It is the headmistresss husband, Monsieur Constantin Heger, a man of impressive intellect and spirit, the first person outside her immediate family to take her seriously, the first man to treat her as a potential equal. But the thrill of having his attention in her first year, as a pupil, has been followed by misery in the second, as his junior colleague. The Hegers have become wary of Charlottes ardour and eccentricities, and much more formal in their dealings with her. And now the man she considered her soul-mate is pretending that she is nothing special to him at all.

She looks in the mirror and sees, with ruthless clarity, a catalogue of defects; a huge brow, sallow complexion, prominent nose and a mouth that twists up slightly to the right, hiding missing and decayed teeth. She looks poor and ill-dressed, haunted and miserable, with none of the brilliant light from her great honest eyes that other people sometimes saw, and marvelled at. [I]t is an imbecility which I reject with contemptfor women who have neither fortune nor beautynot to be able to convince themselves that they are unattractive. Thats what she had written six months earlier, when her friend Ellen, back home in Yorkshire, had ventured to suggest that there was some romantic motive for Charlottes return abroad.

The pain of staying indoors is too much: she sets off along the length of the parc Royal to the porte de Louvain, through the gate and up the long hill heading eastwards away from the city. No inhabitant of Brussels need wander far to search for solitude, she wrote later; let him but move half a league from his own city and he will find her brooding still and blank over the wide fields, so drear though so fertile, spread out treeless and trackless round the capital of Brabant. Her destination is the Protestant Cemetery in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, two miles beyond the walls of this predominantly Catholic city, a walk down into the hamlet of Evere, then up to the crest of a hill beyond. There is no church here, just a few dozen graves in a walled garden, heavily overgrown with cypress and yew, with inscriptions in English, French and German: the foreign tongues of alienated people dying far from home.

Charlotte has come to visit a particular grave, that of Martha Taylor, one of the West Riding family who had encouraged her to come out to Brussels in the first place and whose elder sister Mary had been Charlottes most admired friend since girlhood. Charming, quirky Marthaa flirt and chatterboxhad been swept away by cholera: the last time Charlotte had been out to visit her grave was just two weeks after the funeral the previous October. Emily had been with her then, and Mary, and all three young women had gone back and spent a strange evening at the lodgings of another English family, the Dixons, in the rue Royale. But even that gloomy day seemed better than this utterly solitary one. The Dixons had all left Brussels now, as had Mary Taylor, and Emily was back home in Haworth.

From the cemetery Charlotte keeps walking away from the city, through valleys, farms and hamlets, to a hill where there is nothing but treeless fields as far as the eye can see. The furthest reach. She has to turn back, but coming into the city in the fading light she finds herself so desperately trying to put off returning to the Pensionnat that she ends up weaving around the surrounding streets to avoid it.