Caldicott - A desperate passion: an autobiography

Here you can read online Caldicott - A desperate passion: an autobiography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;Australien;Australia, year: 1996, publisher: W. W. Norton & Company, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

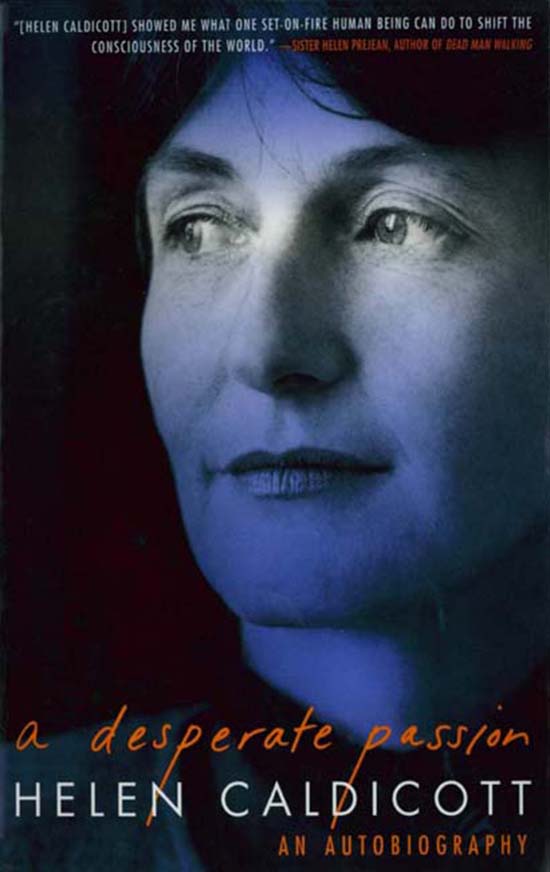

- Book:A desperate passion: an autobiography

- Author:

- Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

- Genre:

- Year:1996

- City:New York;Australien;Australia

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A desperate passion: an autobiography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A desperate passion: an autobiography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A desperate passion: an autobiography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A desperate passion: an autobiography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CHAPTER ONE

W hen I was nineteen, I read a book that changed my life.

It was a novel, barely read these days, called On the Beach, by the Australian writer Nevil Shute (later made into a popular film). It tells the story of the final months in the lives of five people living in a world doomed to be destroyed by radiation after a nuclear war that had begun by accident in the Northern Hemisphere.

Couldnt anyone have stopped it?

I dont know.... Some kinds of silliness you just cant stop, he said. I mean, if a couple of hundred million people all decide that their national honour requires them to drop cobalt bombs upon their neighbour, well, theres not much that you or I can do about it. The only possible hope would have been to educate them out of their silliness.

But how could you have done that, Peter? I mean, theyd all left school.

Newspapers, he said. You could have done something with newspapers. We didnt do it, no nation did because we were all too silly. We liked our newspapers with pictures of beach girls and headlines of indecent assault, and no Government was wise enough to stop us having them that way. But something might have been done with newspapers, if wed been wise enough.

Something might have been done with newspapers, if wed been wise enough...

Shutes story haunted me. Millions of words have since been written about nuclear war and its consequences, and much of the literature is more horrific and emotive than anything Nevil Shute wrote or perhaps even imagined. But his novel was set in Melbourne, the city where I had grown up. It described places I knew, devastated by nuclear catastrophe. Nowhere was safe. I felt so alone, so unprotected by the adults, who seemed to be unaware of the danger.

She passed the grammar school away on the left and came to shabby, industrial Corio, and so to Geelong, dominated by its cathedral. In the great tower the bells were ringing for some service. She slowed a little to pass through the city, but there was nothing on the road except deserted cars at the roadside. She saw only three people, all of them men.... At the end she turned left away from the golf links and the little house where so many happy hours of childhood had been spent, knowing now she would never see it again.

I had already decided to be a doctor, and I came from a family who encouraged me to believe that if I worked hard, I could do anything. But after reading On the Beach, I knew I wouldnt just go through medical school and settle into a nice, cosy, well-paid niche somewhere, as doctors in Australia were apt to do. I wanted a husband and a family, certainly, but somewhere in me was a conviction that I had other work to do as well.

When I read On the Beach, I started to realise what that work might be.

N obody with Polish and Irish ancestryas I havehas any right to expect a quiet, easy life. If I hadnt found that out for myself, I could have learned it by considering the lives of my forebears.

Gracius Jacob Broinowski, my great-grandfather on my fathers side, was a Polish baron, born in 1837, who began his career by avoiding conscription in the Russian army. After escaping from his upstairs bedroom window in the Polish town of Weilun by the time-honoured method of tying sheets together to make a rope, he travelled to Germany and then to England. In about 1857 he came to Australia, where he eked out a living by painting landscapes and scenes of various towns as he travelled around the eastern side of the continent. He married a pretty girl named Jane Smith who smiled at him from her Melbourne window, and after some years they settled in Sydney with their six sons and daughter. Gracius taught painting to private pupils and at colleges, lectured on art, and exhibited at the Royal Art Society.

His greatest claim to fame, however, was as an artist of Australian native fauna. In the 1880s he supplied the school classrooms of New South Wales with pictures of Australian birds and mammals, and between 1887 and 1891 prepared a series of six volumes called The Birds of Australia, which have since become collectors items. His bird prints hang on the walls of my house to this day.

One of my great-grandmothers on my fathers side, Mary Sanger Creed, was a forthright woman and an early feminist. The first woman to matriculate in Australia, she applied to enter medical school in Melbourne. In the 1870s the idea of a woman wanting to be a doctor was considered ridiculous enough to be featured on the front cover of the English satirical magazine Punch; the drawing shows the chancellor of the University of Melbourne holding up a grave, dismissive hand as my great-grandmother attempts to enter the sacred portals. (The first Australian woman to train in medicine didnt receive her degree until 1893, and even then it was from Edinburgh University.)

Mary married a progressive Anglican minister, the Reverend Jonathan Evans, and had four children. She hated being a ministers wife and living in the small Tasmanian town of Deloraine, and she turned to writing. Soon she became known as an excellent journalist, whose articles on a variety of topics appeared in local and national newspapers. When her children were still young, she and Jonathan Evans agreed to part, and he moved to the Riverina district of southwestern New South Wales. Obviously harbouring his own ambitions, he left Australia for England, where he became an actor, while the four children remained with their mother.

In the 1890s the irrepressible Mary and her children moved to a seventy-acre property near Wyong, north of Sydney, where she started a cooperative silk farm for other single women and their dependent children. All the families worked together, growing mulberry trees to feed the silkworms, spinning the silk and selling it. The silk farm was successful for a number of years.

My grandmother, Grace Creed Evans (whom for some reason we called Dais, short for Daisy), was the oldest of Marys four children. A talented musician who played the violin and piano, she helped support the family by performing music on the ships that plied the cities on the eastern seaboard of Australia. Later she became a music teacher. Her youngest sister, Win, was an early Montessori governess who taught the children of Ethel Turner, author of Seven Little Australians and one of Australias most famous early writers.

Grace married Gracius son Robert Broinowski in Melbourne in 1905, where Robert was Usher of the Black Rod in federal Parliament for some years. It was not a happy marriage, as Bob was known to go on bushwalks with various women. He was a prickly, talented man, an amateur poet. Many of his own verses reflect his dalliances and affairs. Others, such as this one, highly descriptive of the Australia bush and its ubiquitous flies, show his irreverent sense of humour.

The road comes winding down the range

Each moment bringing to my eyes

Some point of beauty new and strange

Oh damn the flies...

Ten thousand furies blight the stinking swine

Bright parrots flash with eerie cries;

The lyrebird sings his chorus divine

Oh, flaming bastards... the flies.

Dais and Bob had two sons, my uncle Bob and my father, Theo Philip, who was born in 1910 and was called Philip. In 1927 Parliament moved from Melbourne to its permanent home in Canberra, Australias brand-new federal capital and the site of a former sheep station about 300 kilometres southwest of Sydney. The move gave Bob the excuse he needed to leave Dais and the boys in Melbourne: he eventually married another piano teacher, and they had a daughter, Ruth. My grandfather became clerk of the Senate in Canberra and the designer of the Senate rose garden. His portrait hangs in Parliament House.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A desperate passion: an autobiography»

Look at similar books to A desperate passion: an autobiography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A desperate passion: an autobiography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.