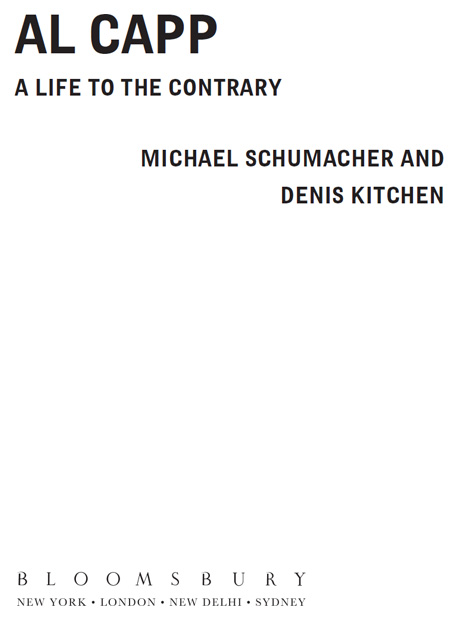

BY MICHAEL SCHUMACHER

Dharma Lion: A Biography of Allen Ginsberg

Crossroads: The Life and Music of Eric Clapton

There but for Fortune: A Biography of Phil Ochs

Francis Ford Coppola: A Filmmakers Life

Mighty Fitz: The Sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Mr. Basketball: George Mikan, the Minneapolis Lakers,

and the Birth of the NBA

Wreck of the Carl D.: A True Story of Loss, Survival, and Rescue at Sea

Will Eisner: A Dreamers Life in Comics

BY DENIS KITCHEN

Al Capps Complete Shmoo (2 volumes)

Lil Abner: The Frazetta Years (4 volumes)

Playboys Little Annie Fanny (2 volumes)

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman (with Paul Buhle)

Underground Classics (with James Danky)

The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen

Chipboard Sketchbook

Copyright 2013 by Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce, or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Schumacher, Michael, 1950

Al Capp: a life to the contrary / Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen. 1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-60819-785-9

1. Capp, Al, 1909-1979. 2. CartoonistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Kitchen, Denis, 1946II. Title.

NC1429.C295S38 2013

741.56973dc23

[B]

First U.S. edition 2013

This electronic edition published in February 2013

www.bloomsbury.com

Once upon a time, long before Garry Trudeau entertained newspaper comic strip readers with his astute political commentary in Doonesbury, before readers visited the Okefenokee Swamp and followed the social satire in Walt Kellys Pogo, before comic strips were aimed at the hearts and minds of adult readers, Al Capp introduced his followers to a hilarious mythical Kentucky hillbilly hamlet known as Dogpatch. The strip, Lil Abner, created and drawn by Capp from the very beginning, ran for forty-three years and, at the height of its popularity, reached a worldwide readership of more than ninety million.

Although it had its charm, Dogpatch was populated by folks just a few steps behind modern big-city ways. Turnips provided the town with its only known source of income, pigs were raised as both pets and a primary food source, single women literally chased eligible bachelors in the annual Sadie Hawkins race (with the captured men forced into wedlock), and creatures with such unlikely names as shmoo, kigmy, and bald iggle dropped by as figures in Capps humorous observations on the human race. Politicians and businessmen did their best to bilk Dogpatchers out of the puny bit they did possess. The typical story ran for weeks on end, until even Capp himself seemed occasionally befuddled over where his winding plots would end up.

Abner Yokum, the strips title character, lived with his parents, Mammy and Pappy Yokum, and by all appearances had everything a perennial nineteen-year-old could possibly want. He was tall, handsome, muscular, and constantly being pursued all over the hills by Daisy Mae Scragg, the most beautiful single girl in Dogpatch, who, for reasons escaping any other male in the vicinity, wanted only a man totally uninterested in her. Abner was nave on his best day, dumb as a fencepost on his worst, and always caught up in an adventure more complicated than his native intelligence could handle. Al Capp delighted in working him in and out of trouble, using his predicaments as stagings for satire, parody, and a brand of comedy that won the praise of Charlie Chaplin, John Steinbeck, Hugh Hefner, John Updike, and a host of others.

Capps rise to prominence was swift and unprecedented. As far back as the turn of the twentieth century, comic strips had bolstered newspaper circulations and earned their creators fame and fortune. Hogans Alley, an early comic dynamo featuring a kid wearing what appeared to be a yellow nightshirt, touched off newspaper wars, while a beautiful surrealistic strip called Little Nemo in Slumberland guided its readers through previously unexplored regions of the subconscious. Other strips and one-panel cartoons aspired to do little more than deliver daily punch lines. Action and adventure strips, boasting of long-running plots that held readers attention for weeks and even months, were capturing the countrys fancy right about the time Lil Abner made its debut.

Capp had no idea where his strip would take him; he only knew that he wanted to succeed as a cartoonist. He knew, from an early age, that he could draw, and hed kicked around art schools and worked on a few short-lived jobs before landing a breakthrough job as an assistant to Ham Fisher, the creator of the enormously popular boxing strip Joe Palooka. It was only a matter of time before Capp struck out on his own.

The world was ready for Lil Abner, which started out as an adventure strip but quickly developed into a humorous feature with long-running stories usually associated with such comics-page favorites as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, or Little Orphan Annie. Readers, still bruised from the Depression and fearing the events in Europe leading to World War II, connected with Capps adult humor, outrageous adventures, buxom female characters, and snide but spot-on commentary. Lil Abner shot to the top in very little time and would become one of the most widely read strips in comics history. Capp was a wealthy man before he celebrated his thirtieth birthday.

But this was only the beginning. Restless and hypercreative by nature, Capp trained his sights on how to broaden his artistic and financial horizons. His marketing genius led the way. Besides developing ideas for new comic strip titles, he pushed to find ways to nudge his Lil Abner characters off the comic strip pages and into previously unexplored or barely explored territories. There were product endorsements and, more lucrative yet, merchandising blitzes tied into the strip. In one year alone, the shmoo, a cuddly little critter capable of providing humanity with everything it ever needed, grossed $25 million in merchandisingand this was mid-twentieth-century dollars.

Capp created a new template for the successful comic strip artist as he went along. Lil Abner blazed the trail for such future marketing phenoms as Peanuts and Garfield. Then, when Dogpatch USA opened its gates in 1968, Capp became the only cartoon creator other than Walt Disney to have his own theme park. By that point, Capps face had appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek, he was a regular contributor to Life, his mug had been seen on countless newspaper and magazine ads, and he was a regular guest on television, most notably The Tonight Show. Comics artists had almost always been solitary figures spending hours alone at the drawing table, collecting good salaries but remaining relatively unknown to the public. Al Capp changed all that, through the force of sheer ambition, talent, marketing know-how, and a winning personality.