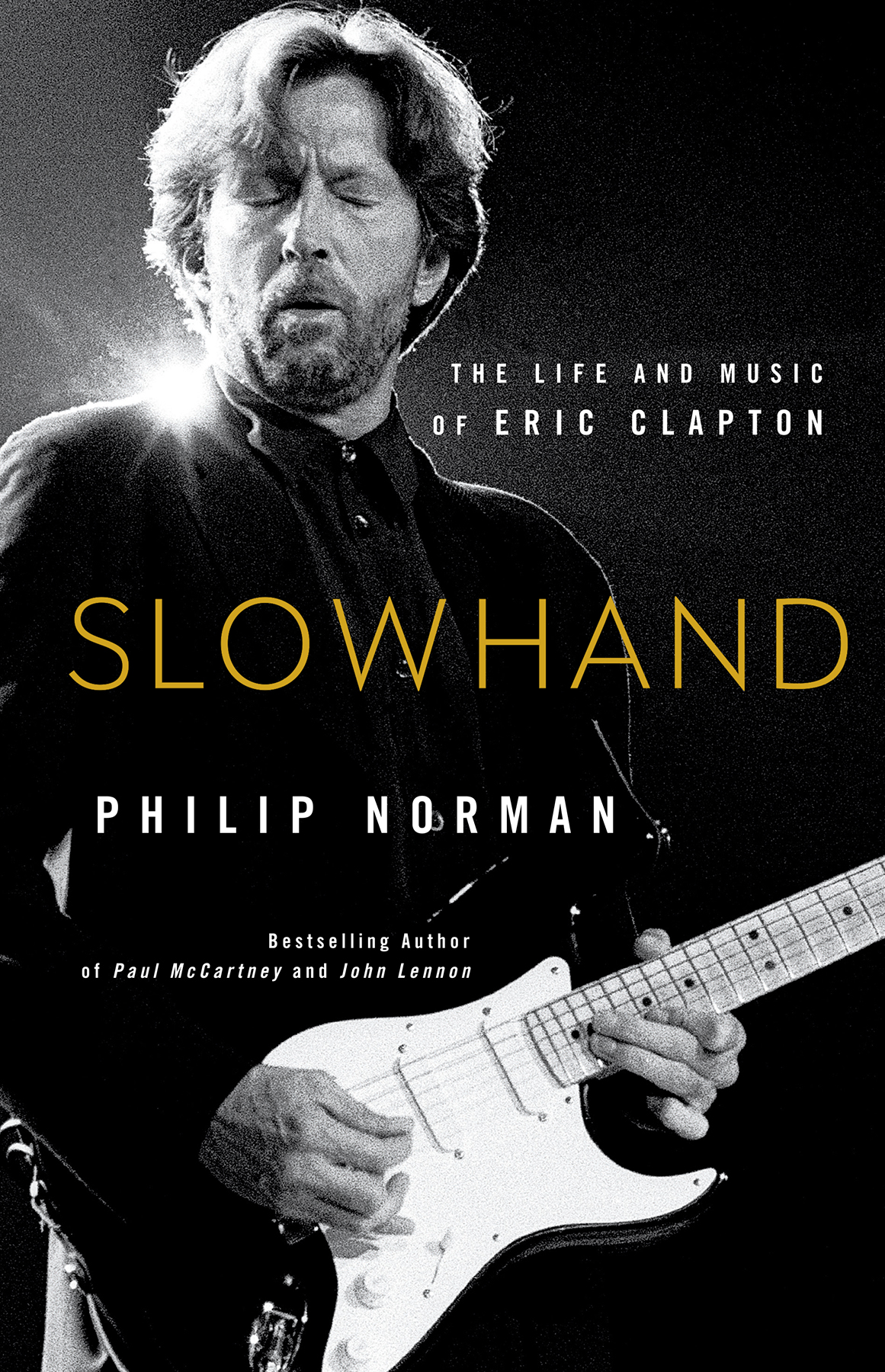

I ts December 1969, and lunchtime in a busy motorway cafeteria a few miles south of Leeds. Standing in the self-service queue are half a dozen young men whose shoulder-length hair, biblical beards and homespun clothes give them the look of nineteenth-century evangelists. Their fellow customers recognise them as rock musicians, pick up their mostly American accents and stare with curiosity or hostility, but no one yet realises that they include George Harrison.

Since the time of Americas Moon landing in July, it has been clear the Beatles are headed for break-up and that, with the saddest synchronicity, they and the 1960s may come to an end together. But every press report has the fractious four battling behind closed doors in Londons Mayfair. How can one of themespecially the most private, fastidious onepossibly be 170 miles to the north, in this unsympathetic environment of harsh strip-lights, clashing trays and greasy smells?

George is interrogating a female counterhand as to whether the mushroom soup of the day contains meat. Its mushroom soup, she reiterates patiently, still not recognising the face behind the beard or the voice. It could be made with meat stock, though, George persists. Im a vegetarian, you see Meanwhile, the bushy-bearded, fur-coated figure whos next in line loads a plate with eggs, chips, bacon and baked beans and, for dessert, chooses a portion of synthetic-looking trifle in a frilled paper cup. Hes the twenty-four-year-old Eric Clapton. At the cash-register, he remembers hes carrying no moneyin this case not a mark of poverty but royalty. Can anyone lend me a pound? he asks with a shamefaced grin at the incongruity of it.

The two choose a table in a deserted sector, where their companions respectfully leave them by themselves. George starts to eat his mushroom soup in the way taught at young ladies finishing-schools, tilting the bowl away from him, plying his spoon outwards. After a few spoonfuls, he detects the presence of meat and pushes the bowl aside. By now, hes been noticed, if not yet positively identified, by a trio of women nearby, collecting dirty crockery with a trolley. After a murmured conference, their crew-boss, a formidable-looking Yorkshire matriarch, approaches and says, It is you, isnt it?

No, George replies.

But theres no escape: the women crowd round, paper napkins are produced and, dutiful Beatle that he still is, he signs them as directed for Sharon, June and their leaders grandson, little Willis. Why dont you ask Engelbert here for an autograph as well? he suggests.

The trio turn to the table-companion whos quietly working his way through his outsize fry-up. In truth, the most ardent Eric Clapton fans, even those who regard him as God, might have difficulty in recognising him today. His Apostolic beard is newly grown, replacing the earnest Zapata moustache he previously wore in homage to his best friend George, which in turn had superseded a mushroom-cloud Afro copied from Jimi Hendrix. No one else in his profession changes their look so frequently and radically. To these three least likely aficionados of psychedelic rock, all that can be said for certain is that he isnt Engelbert Humperdinck.

Actually, George continues in the same flatlining tone, this is the worlds greatest white guitarist Bert Weedon.

Another Beatly in-joke: few of Britains modern guitar stars would be where they are today without Weedons Play in a Day tuition-book. But with his lounge suits, crinkly dyed-blond hair and big white Hofner President, no one less rock n roll than dear old Bert can be imagined.

The trolley-boss realises its a wind-up, bridles with annoyance, but makes one last sally on behalf of little Williss autograph collection. Are you a group as well? she asks Clapton sternly.

No, he says, avoiding her eye. Just a hanger-on.

Not every famous bands break-up is a world-stopping tragedy like the Beatles. Just a year prior to this encounter, the supergroup Creamconsisting of Clapton, drummer Ginger Baker and bass-player Jack Bruce and so named because each was previously in a top groupseparated after only two years together. A fusion of old-fashioned blues with embryo heavy metal and freewheeling modern jazz, Cream were largely responsible for transforming pop into louder, more male-oriented rock; in their brief career they sold 15 million albums, of which the third, Wheels Of Fire, was the first double one to go platinum twice over.

Clapton has a history of walking out of bands at their peak (first the Yardbirds, then John Mayalls Bluesbreakers), but this time his well-known restlessness was less a factor than the mutual, often violent hostility between Bruce and Baker in Creams premature curdling. Anyway, these days top bands continually split and re-form in different shapes like amoeba in a psychedelic light-show. Throughout the Anglo-American rock community, musicians are resigning from ensembles where they feel misunderstood, or whose commercial success has begun to weigh on them, and joining up with kindred spirits to play the kind of stuff theyve always really yearned to.

When Graham Nash quits the Hollies to team with David Crosby from the Byrds and Steven Stills from Buffalo Springfield as Crosby, Stills and Nash, it seems that this pooling of top-level talent cant get any better. But then, seven months after the end of Cream, Clapton and Ginger Baker are revealed to have joined forces with vocalist-organist Stevie Winwood from Traffic (and before that, the Spencer Davis Group) and bass-player Rick Grech from Family. Eschewing the new fashion for baptising bands with their members surnames like law firms, the super-supergroup will be called Blind Faith.