Contents

Landmarks

Page List

Also by Julian Guthrie

The Grace of Everyday Saints

The Billionaire and the Mechanic

How to Make a Spaceship

Alpha Girls

Copyright 2020 Julian Guthrie

For photograph credits, see

Cover 2020 Abrams

Published in 2020 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932361

ISBN: 978-1-4197-4331-3

eISBN: 978-1-64700-015-8

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

To all the brave and innovative doctors, nurses, donors, and volunteers on the front lines of medicine and research

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

The Making of a Superhero

James Christopher Harrison peered out the paned living-room window of his family home in the railway town of Junee in New South Wales, Australia. He rubbed a circle where his breath fogged up the glass. His mates were out playing cricket in the street, and the ten-year-old pleaded with his mom to let him out.

They dont have enough players! he protested.

Mum, they need me! he tried again.

They have a terrible bowler! he said of the pitcher.

Jamess desperate entreaties went nowhere, blending into the background noise of the whistle of passing trains and the shouts and cheers of his friends in the street.

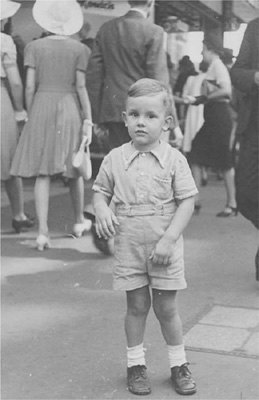

He had been ordered indoors until his latest cold passed, a torturous fate for a boy who just wanted to play like the rest of the kids in the small town. With big, dark brown eyes, light hair, and an innocent expression that masked a mischievous streak, James had always been a small and sickly child, picking up any cold or bug that went around Junee in the 1940s. During World War II, Jamess mom received extra rations of butter, milk, meat, and bread because of Jamess poor health. She tried her best to fatten him up with his favorites, bangers and mash and stone fruit pies.

Finally, after lunch, when the neighborhood boys had moved on from their game of cricket and taken their makeshift wicket with them, James resorted to a game of tag with his younger sister inside the house. No matter that he still hadnt finished his meal. As he raced around the house while eating, he ran into a wall, and the spoon in his mouth was violently launched into the back of his throat. Off to the hospital they wentagain.

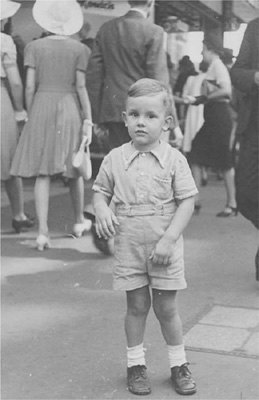

James Harrison at around age four, Junee, Australia.

When James wasnt battling some ailment, he was outdoors every moment he could grab, playing cricket or inventing battles, games, and races with his best friends, Ronny and Johnny Marshall.

One weekend afternoon, the three boys decided it was time for a race to the railroad tracks on their bikes. James had Ronny perched on the handlebars of his rickety bike, while Johnny was on his own bike, gunning to pass them. The boys had a block to go before crossing the train tracks that sliced through Junee. The whistle of the approaching train propelled them forward like the starter pistol at a race. James stood in his seat, gripped his handlebars, and glanced back at his competition.

Holy smokes! Johnny yelled.

Just then, a truck of some sort careened around the corner, coming out of nowhere. James veered but wasnt quick enough and smashed headlong into the back of the fast-moving vehicle. Johnny veered and just missed the pileup but slid across the road. Slowly, unsteadily, the bruised and battered boys picked themselves up.

Crikeywhat happened? James said, helping Ronny up.

James scratched his head with a bleeding hand and said, How did the medics get here so fast?

You idiot! said one of the boys. Look!

When the reality of what had happened set in, the ribbing began: Only James Harrison would run into the back of an ambulance.

These were the kind of scrapes and scares that punctuated James Harrisons boyhood. But when he landed back in the hospital in 1951, it was for something far more serious than bruises, cuts, and bad colds. James, now fourteen, had caught something he couldnt shake. A bug had turned into bronchitis and then triple pneumonia. Penicillin was doing nothing to prevent the infection from spreading from one lung to the other. The tissue of Jamess lungs was inflamed, and he coughed constantly, complaining of sharp chest pains.

James was transported to St. Vincents Hospital in Sydney in a bid to save his life. There, Jamess mom and dad, Peggy and Reginald, met with a young surgeon, Harry Windsor, who had honed his skills as a doctor during World War II, serving mostly in New Guinea with the Australian Army Medical Corps. Dr. Windsor had made a name for himself at St. Vincents through his pioneering work in heart valve surgeries. He had established the thoracic surgery department, and even organized the hospitals staff cricket team, serving as coach. He endeared himself to his surgery patients by sleeping next to their beds.

But the operation involving young James would be Dr. Windsors first pediatric pulmonary lobectomy, and James was in bad shape. The lobectomy of the lung was a surgical operation to remove an infected or diseased portion of the lung. Dr. Windsor was not certain whether the boy would make it.

Ive got my lucky penny, James told the doctor when they met, showing him a flattened coin. He explained that he and his friends would wait for the trains of Junee to get close before placing pennies on the tracks and watching them get squashed. The boys had pockets full of squashed pennies.

James charmed doctors and nurses alike with his chatter and good spirits. In the days leading up to the surgery, James endured relentless tests, gagging every time antiseptic was sprayed into his mouth, and closing his eyes when exploratory tubes were pushed down his throat. The tubes felt larger than his throat. When they were removed, James could finally uncurl his fists and run his fingers over his flat penny. The nurses came to him every day for blood draws. Of the four major blood groupsA, B, AB, and OJames was universal blood type O negative, the blood of choice in emergency rooms and for use in transfusions. Just 7 percent of the population has O negative blood. With no major blood group antigens, O negative blood is the ideal for recipients with any blood type. But James, as O negative, could only safely receive transfusions of O negative blood. The positive or negative factors on ones blood were determined by a protein called the Rh factor, which can be present (+) or absent (), creating the eight most common blood types of A+, A, B+, B, O+, O, AB+, AB. Compatible blood for transfusions meant the difference between life and death.