MATILDA

Copyright 2019 Catherine Hanley

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018962168

ISBN 978-0-300-22725-3

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For James

CONTENTS

MAPS AND TABLES

Maps

Genealogical tables

ILLUSTRATIONS

).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A S EVER I AM GREATLY indebted to a number of friends and colleagues for their assistance and encouragement, and it is a pleasure to thank them here.

Heather McCallum and Rachael Lonsdale at Yale were enthusiastic from the start about a new book on Matilda, as was my agent Kate Hordern, who has been a tower of strength throughout; they have all helped me to navigate my way along a lengthy path. Marika Lysandrou has been a rock throughout the latter stages of the publication process, and her help with the intricacies of the plate section was much appreciated.

Helen Castor, whose own book She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England before Elizabeth (along with its associated TV series) shines a spotlight on Matilda, was kind enough to read and comment on large swathes of draft text, particularly those that related to issues of gender and to Matildas relationship with her half-brother Robert of Gloucester; I am extremely grateful for her time and insight.

Susan Brock, my former colleague, now supposedly retired, read through the draft book in its entirety and was as always both indefatigable and insightful; the end result is much the better for her ideas and attention to detail.

My thanks also go to Levi Roach, an expert on medieval Germany and the Salians, who read . Any errors or inaccuracies that remain in the book are of course my own; please feel free to send me tweets written entirely in capital letters.

The sourcing of images for the plate section was made considerably easier thanks to the advice and generous contributions of a number of people and institutions: I would particularly like to thank Oliver Creighton, James Lancaster, Jon Mann, the Anarchy? War and Status in Twelfth-Century Landscapes of Conflict project of the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Exeter, the Friends of Reading Abbey, the British Library, the Parker Library, Roxburghe Estates and all those who upload their images to the Pixabay photo-sharing website along with permission to reproduce them.

On a personal level I would like to express my love and gratitude to my three wonderful children, for whom the arrival in the post of replica swords and spearheads no longer comes as any surprise; and to my long-suffering husband James, who works in a field about as far removed from medieval studies as it is possible to get. This one, finally, is for you.

Map 1 England in the twelfth century

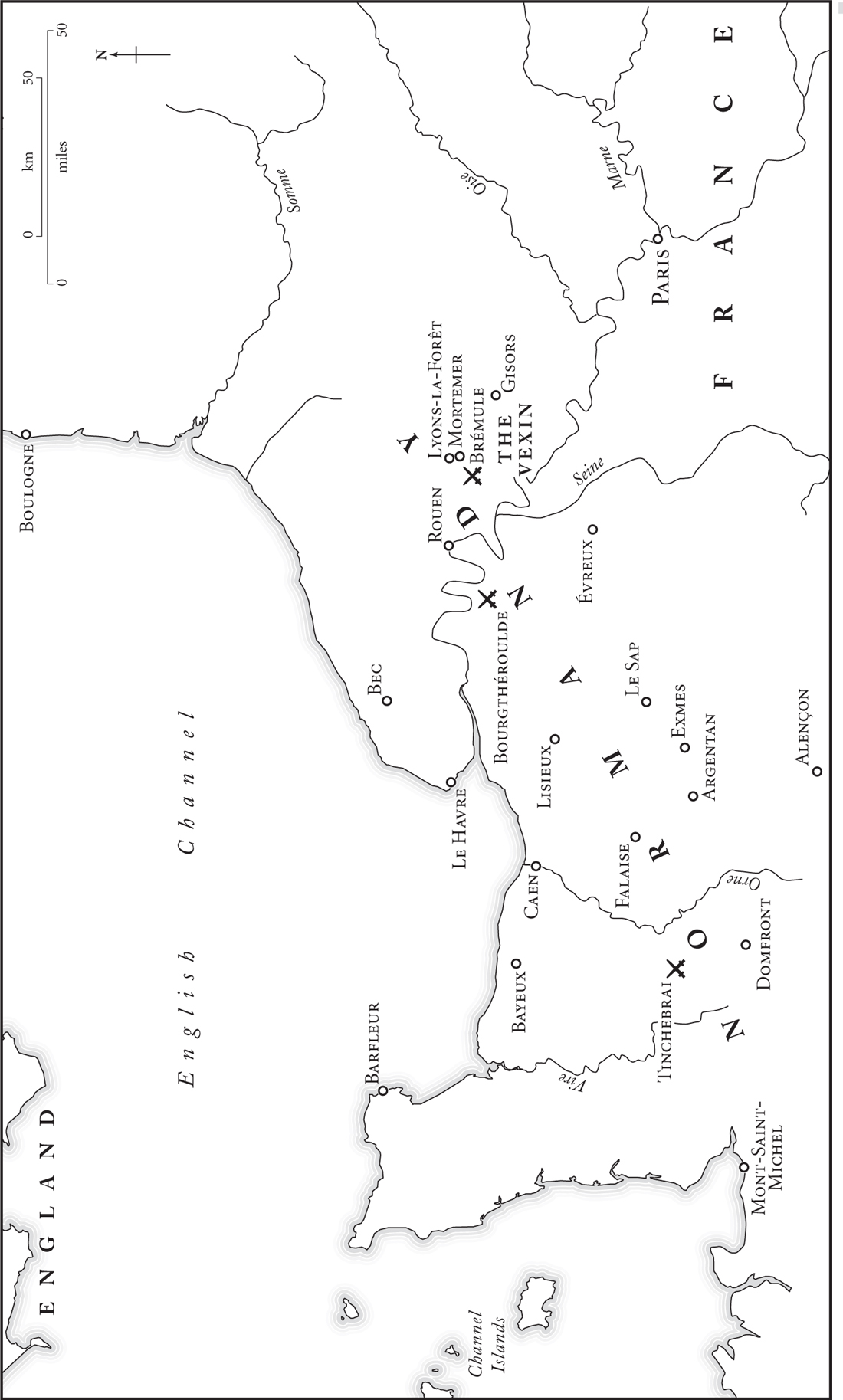

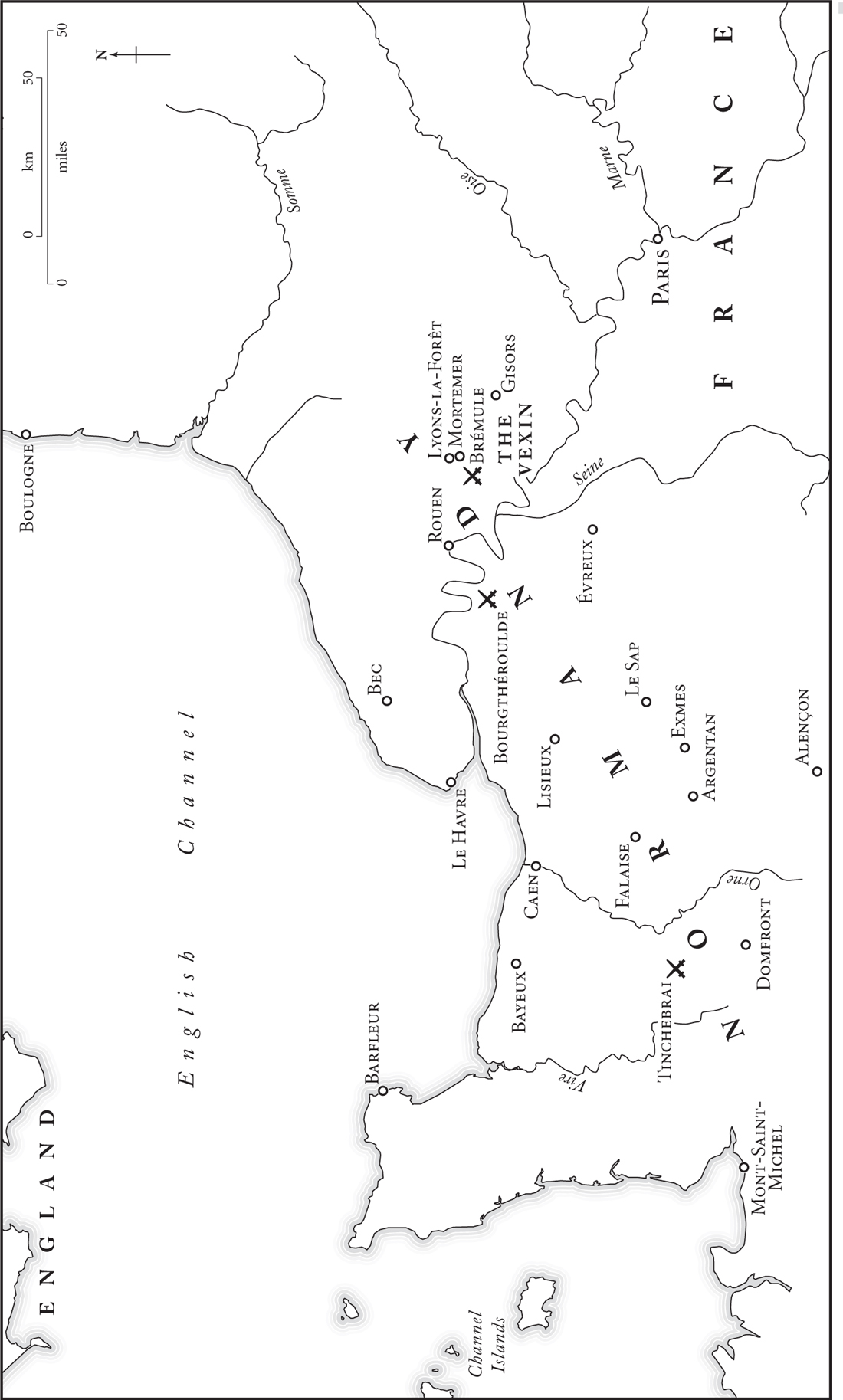

Map 2 Normandy in the twelfth century

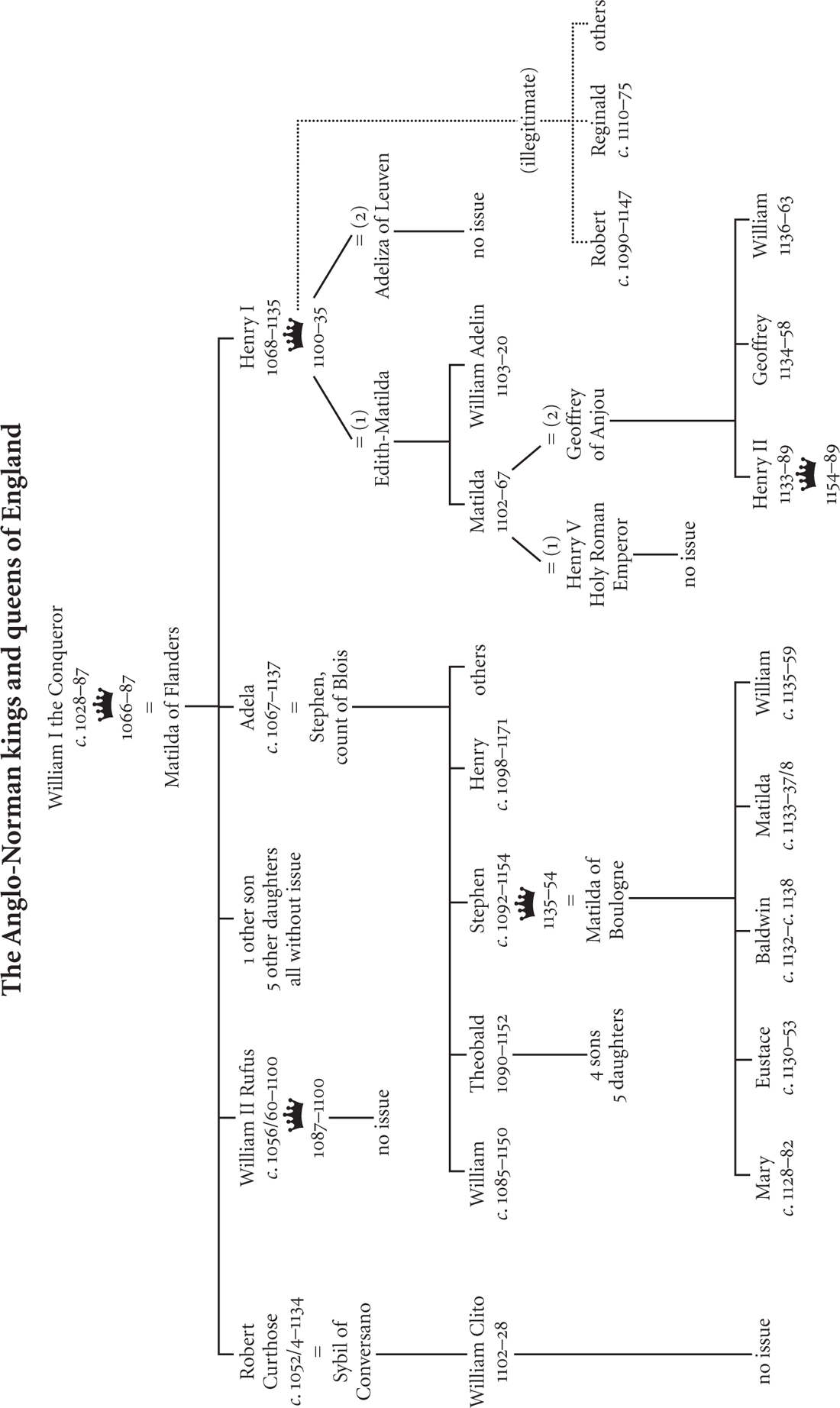

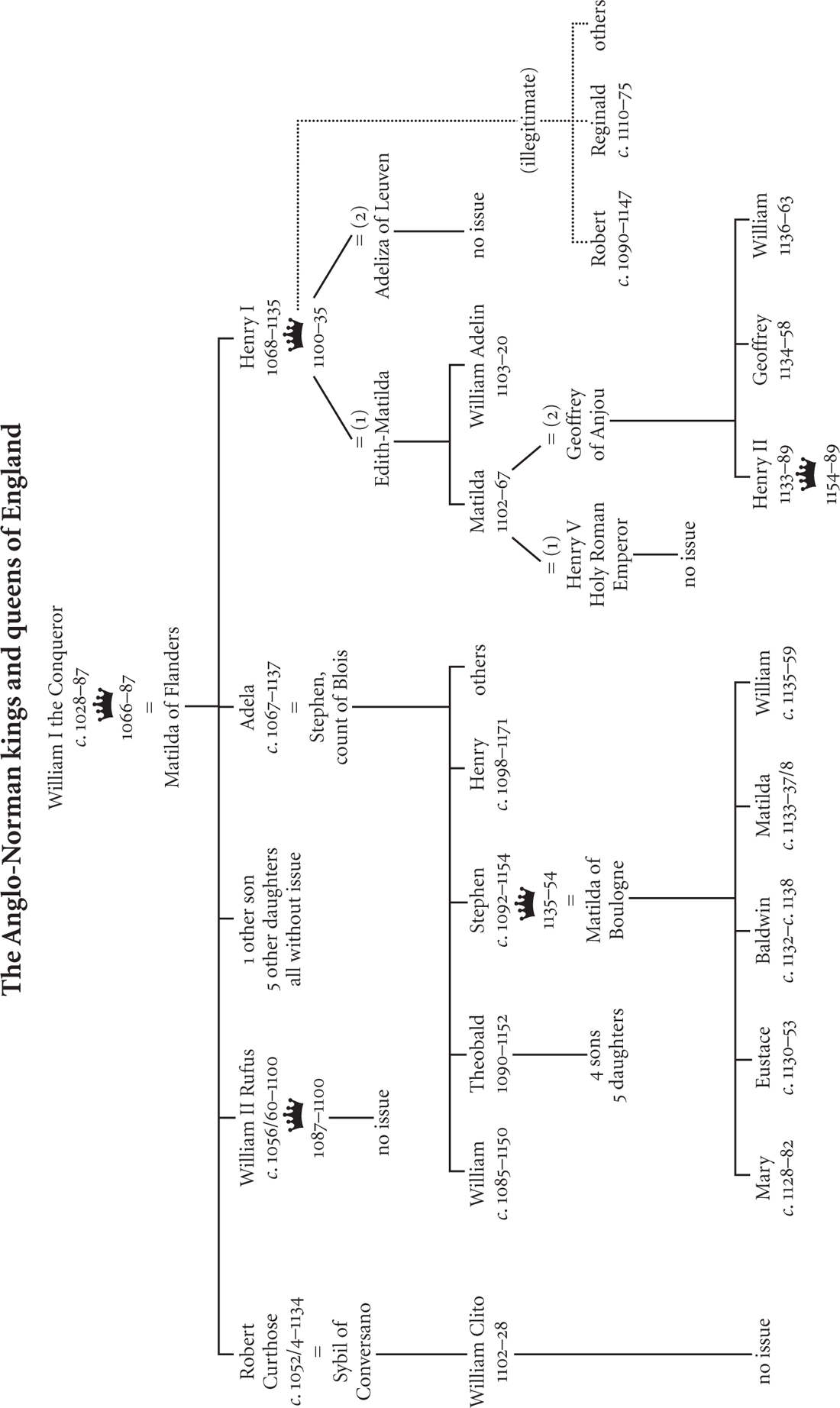

Table 1 The Anglo-Norman kings and queens of England

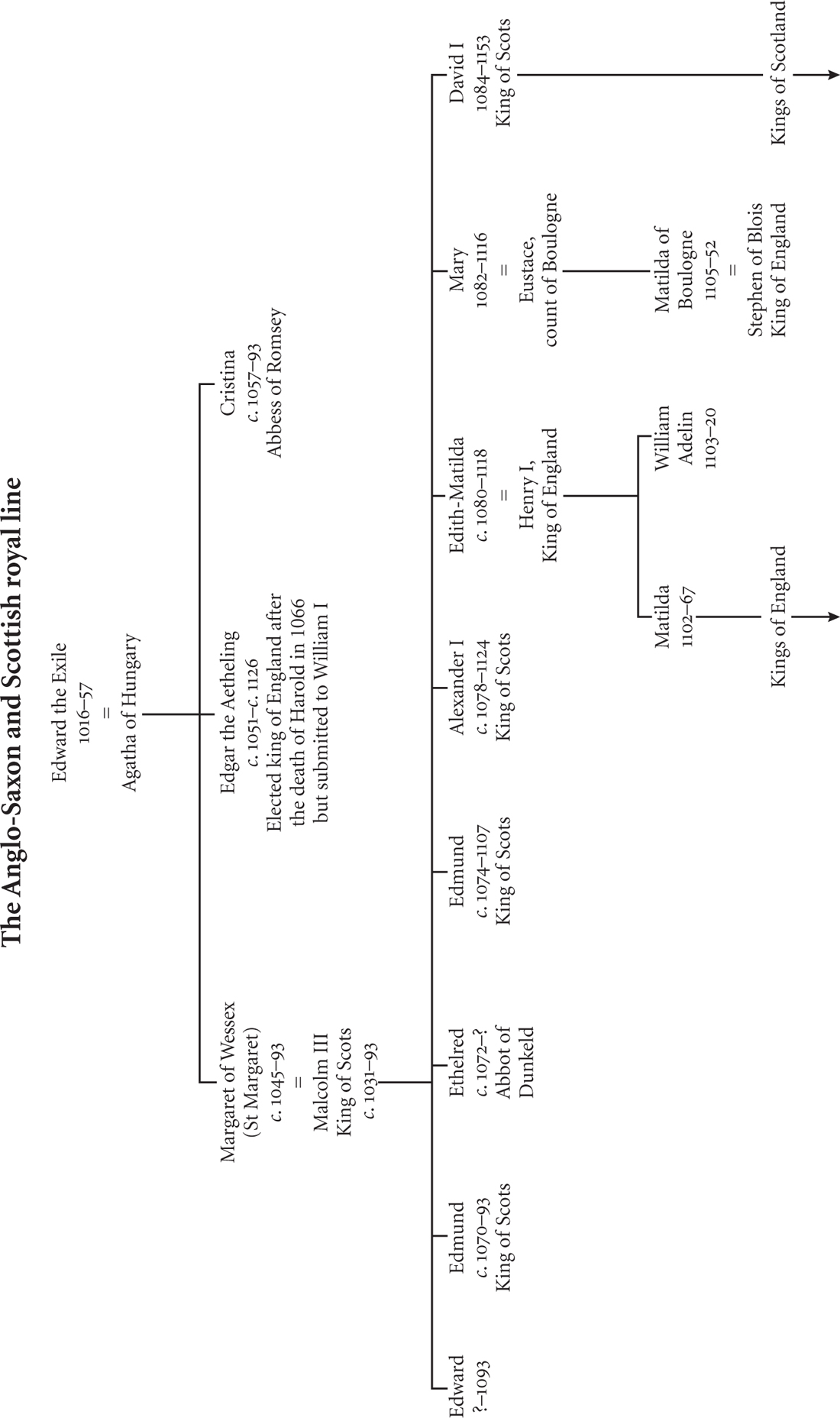

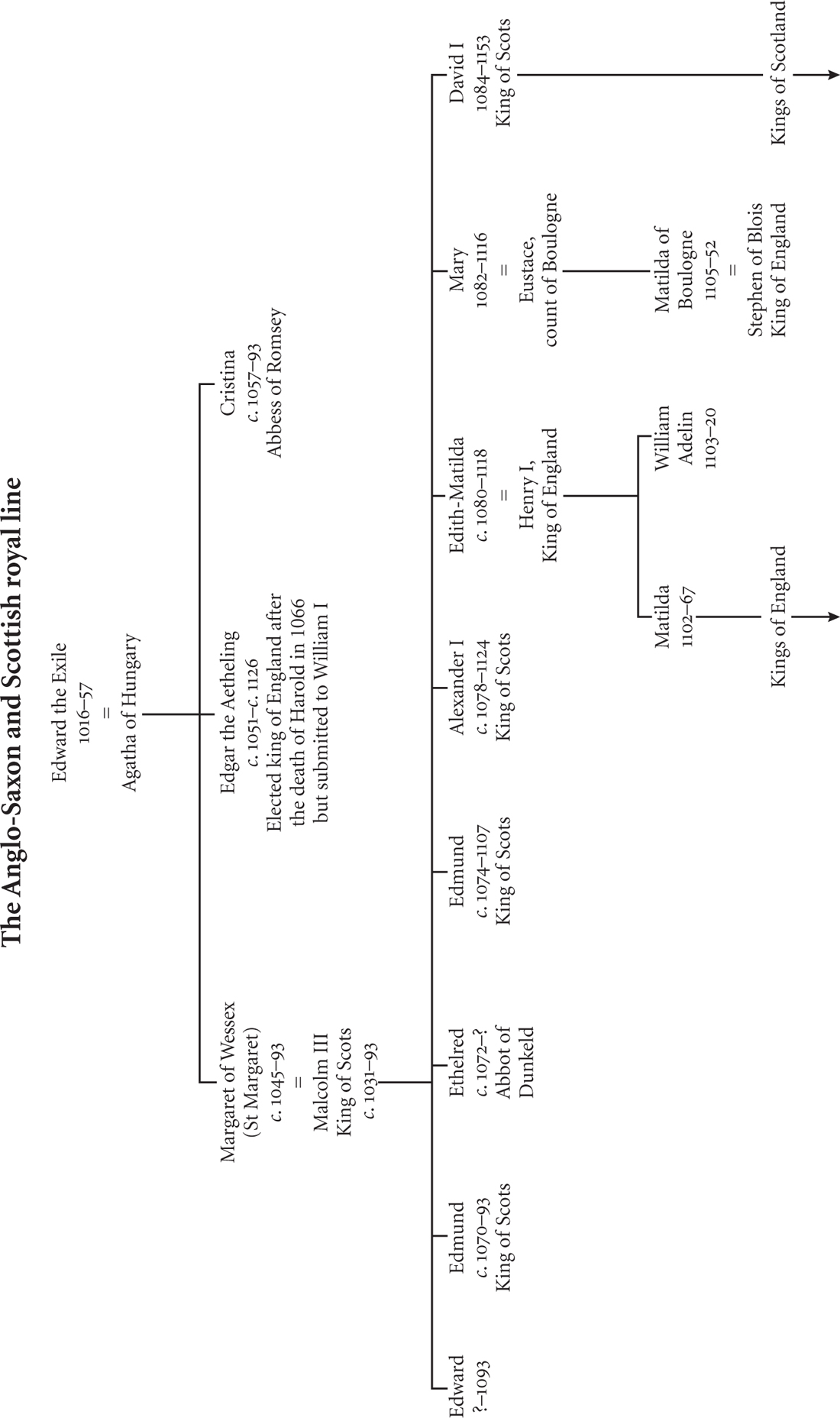

Table 2 The Anglo-Saxon and Scottish royal line

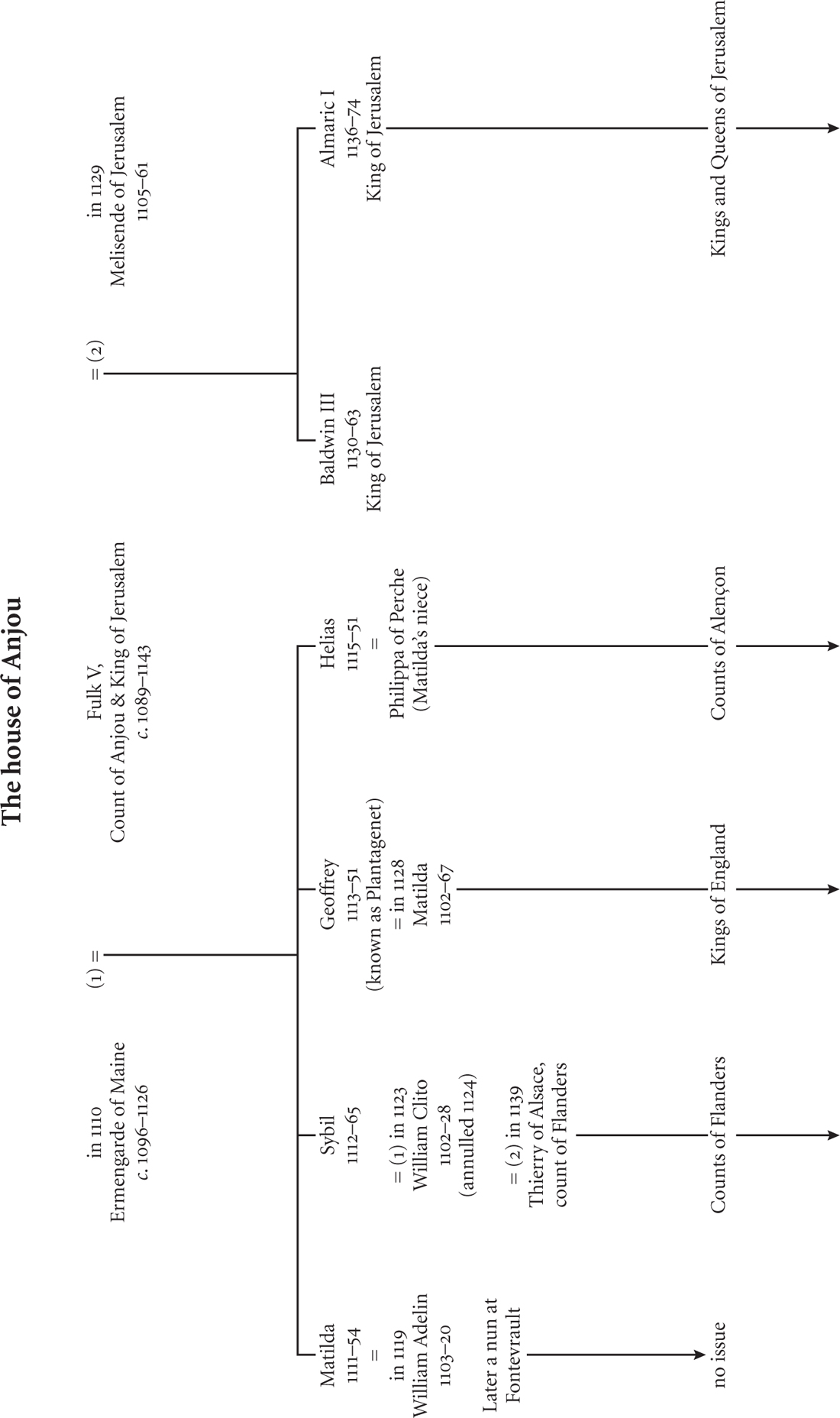

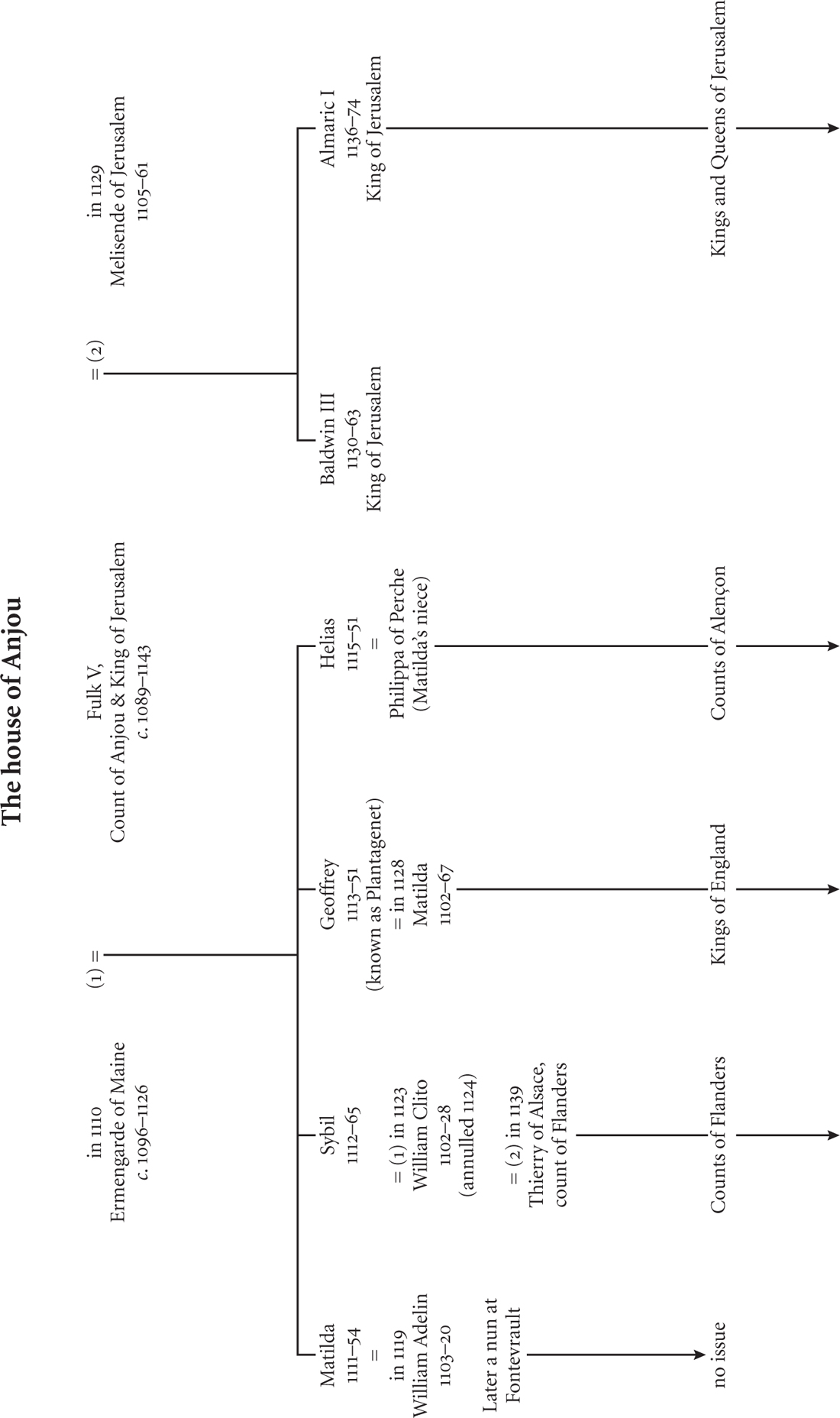

Table 3 The house of Anjou

INTRODUCTION

Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring

Here lies the daughter, wife and mother of Henry.

S O READS THE EPITAPH INSCRIBED on the tomb of Matilda: queen, empress and one of the most remarkable individuals of the Middle Ages. These words were commissioned by her son, Henry II, king of England, and they reflect his desire to honour her memory while making sure that his own importance was foregrounded. But the rather patronising description of Matilda as a daughter, wife and mother commits the all-too-common error of defining a woman only by the men around her: Matilda was indeed all of these things, but she was also a leader, a ruler, a strategist and an able military general in her own right.

Despite the odds being stacked against any woman assuming the throne, England and Great Britain have been subject to a number of illustrious queens regnant over the centuries. All of them owe a great debt to the woman who came first, who fought for her rights, and who proved that royal power could be both held and transmitted in the female line. The kings, too, should be grateful: since Matilda fought to put her son on the throne, every subsequent monarch of England or Britain has been directly descended from her. Were it not for her efforts to overturn the status quo, the mighty Plantagenet dynasty would never have occupied the throne of England, and neither would the Tudors, the Stuarts or any of the later houses.

Matildas story is therefore an important one, but it has rarely been told. There are a number of reasons for this. The first is that, compared with a modern subject, the available contemporary evidence on her life is meagre. We do not really know what she looked like, for example, which is a considerable disadvantage when attempting to envisage or depict her. There are very few contemporary images or even descriptions of Matildas physical appearance, apart from the occasional conventional epithet noting that she was noble or beautiful. Nor do we have much insight into her private thoughts or views; one of the greatest frustrations for the biographer of a twelfth-century individual is the lack of personal correspondence or diaries. Only a very few of Matildas letters have survived dating from the later stages of her life (although these do give a flavour of her character and style, as we shall see) which means that her own voice is noticeably almost absent from the story.

All of the above might well apply to any twelfth-century figure, but in Matildas case the situation is compounded by her being a woman. She lived at a time when daughters were thought to be of lesser value than sons, and many noble (even royal) families did not bother to record their births with any care. Indeed, in some cases noble women or girls of this period are simply known to us as the daughter of a male magnate, without even a reference to their own names. This, of course, is not the case with Matilda, but it is a reflection of the fact that women were deemed to be of lesser importance, that they held fewer public roles and are therefore vastly less likely than men to appear in official documents such as charters and grants. Women also feature less frequently in the chronicles of the period, and when they do they are seen through the invariably male (and often clerical) eye of the writer. This is a point to which we will return later.

Next page