Copyright 2011 by Tracy Borman

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of

The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

BANTAM BOOKS and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain as Matilda: Queen of the Conqueror by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group Limited, London, in 2011.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Borman, Tracy.

Queen of the Conqueror : the life of Matilda, wife of William I / Tracy Borman.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-553-90825-1

1. Matilda, Queen, consort of William I, King of England, d. 1083. 2. Great BritainHistoryWilliam I, 10661087Biography. 3. William I, King of England, 1027 or 81087Marriage. 4. QueensGreat BritainBiography. I. Title.

DA199.M39B67 2012

942.021092dc23

[B]

2011029689

www.bantamdell.com

Jacket design: Belina Huey

Jacket photograph: Richard Jenkins

v3.1

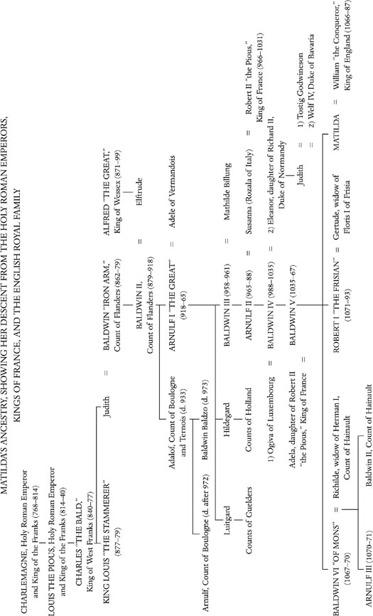

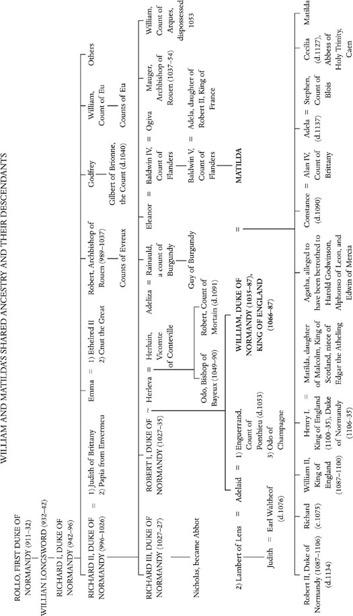

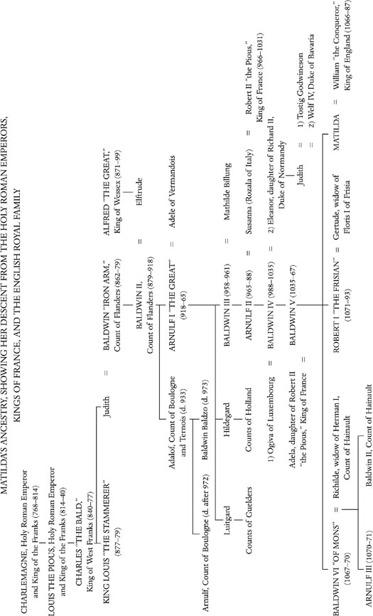

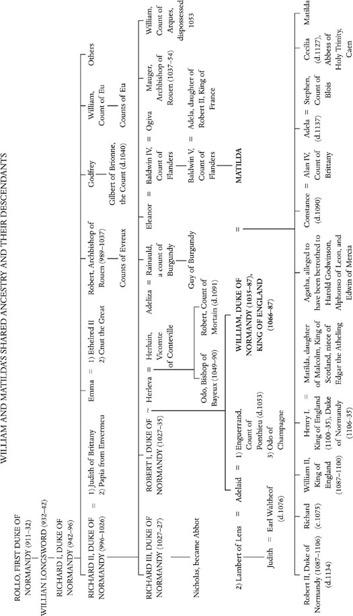

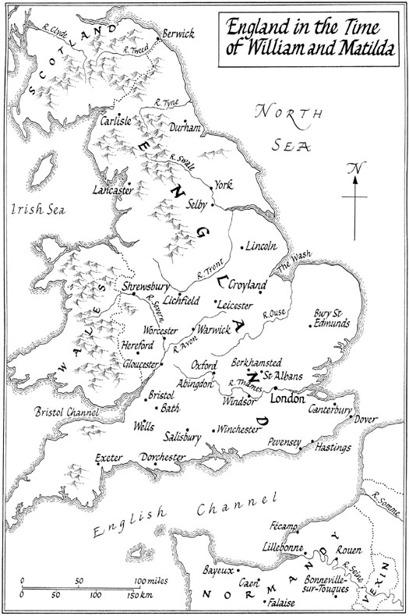

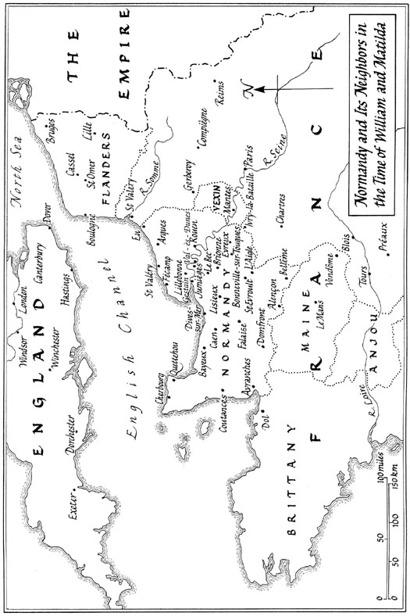

CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A nineteenth-century sketch of Matilda ( National Portrait Gallery, London) An engraving of a fresco showing William and Matilda (Bibliothque nationale de France) Engraving from frontispiece to Agnes Stricklands Queens of England series (illustration by G. P. Harding, Esq., produced expressly for Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman Conquest , vol. 1 Cambridge University Press) Abbey of La Trinit ( Olivier Petit) Abbey of St.-Etienne The castle at Falaise (Getty Images) ) Illustration showing the descendants of William and Matilda (British Library Board) Harold Godwinson swears an oath recognizing Williams claim to the English throne (Muse de la Tapisserie, Bayeux, France/with special authorization of the city of Bayeux/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library) The Mora (Muse de la Tapisserie, Bayeux, France/with special authorization of the city of Bayeux/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library) Matilda watching her husband set sail for England in 1066 ( Mary Evans Picture Library) The White Tower (Getty Images) William and Matilda granting a charter (illustration from Hutchinsons Story of the British Nation , c. 1920 [color litho] by Lucas, John Seymour [18491923]. Private Collection/The Stapleton Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library) A charter bearing Matildas signum (reproduced with permission from Canterbury Cathedral Archives. Ref. No. CCA-DCc-ChAnt/A/2) Statue of Matilda, Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris ( Marie-Lan Nguyen) Matildas tomb GENEALOGICAL TABLES

INTRODUCTION

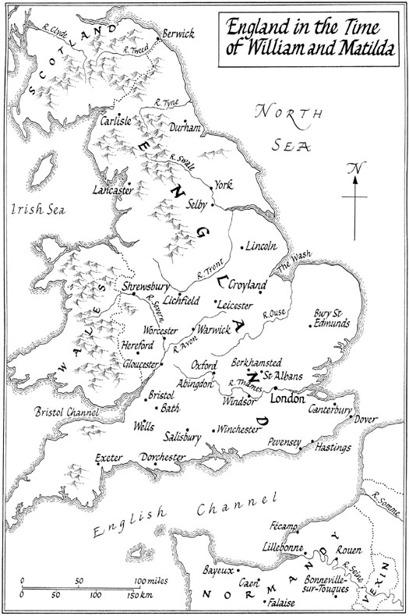

A round the year 1049, William, Duke of Normandy and future conqueror of England, rode furiously to the palace of Baldwin V, Count of Flanders, in Bruges. Upon reaching it, he encountered the object of his rage as she was leaving the palace chapel: Matilda, the counts only daughter. This headstrong girl had dared to refuse his offer of marriage, haughtily declaring that she would not lower herself so far as to accept a mere bastard. Without hesitation, the young duke dragged her to the ground by her hair and beat her mercilessly, rolling her in the mud and ruining her rich gown. Then, without another word, he mounted his horse and rode back to Normandy at full speed. Shaken and humiliated, Matilda was helped to her feet by her terrified ladies and carried home to bed. A few days later, she shocked her family, the court, and most of Europe by declaring that she would marry none but William. Thus began one of the most turbulent marriages in history.

Matilda of Flanders was the diminutive yet formidable wife of William the Conqueror. She broke the mold of female consorts and established a model of active queenship that would influence her successors for centuries to come. By wielding immense power in both Normandy and Englandnot just on behalf of her husband, but at times in direct opposition to himshe confounded the traditional views of women in medieval society. Her remarkable story is played out against one of the most fascinating and transformative periods of European history. Dutiful wife, ambitious consort, doting mother, cold pragmatist, proud scion of a noble race, her character emerges in all its brilliantly contrasting facets.

And yet Matilda has been largely overlooked by historians, and there has never been a full biography of her in English. In the many modern-day accounts of William the Conqueror and the Norman invasion, his wife is accorded little more than an occasional reference. One leading medievalist has dismissed her as a completely colourless figure, and in a printed collection of contemporary legal documents (in which her name features time and again) she does not even warrant her own place in the index, which lists her instead under the entry for her father, Baldwin V of Flanders.

Such neglect can be blamed partly upon the perceived lack of contemporary sources for Matildas life. The lives of women in this period are often so scarcely covered that it raises the question of whether it is possible to write a biography of any of them. The Bayeux Tapestry, for example, depicts six hundred men and only three women, and as a leading authority has observed, the bulk of medieval records were written by men for men. Moreover, even if women had wished to contribute to the historiography of the age, most were illiterate.

Nevertheless, there is a staggering array of contemporary records upon which I have been able to draw for this biography. The eleventh and early twelfth centuries were a time of intense activity among monastic historians. Motivated by a desire to preserve the traditions of their communities, they would spend many hours in the scriptorium recording the history of their own religious house, including the lives of its abbots and lay patrons. This grew to encompass local, national, and even international events that occurred during their lifetime or that could be remembered by the elders of the community in which they lived.

The accountsor chroniclesthat emerged from the labors of monks across England and Normandy span the entire period of Matildas story. Some were written at the time that the dramatic events of her life unfolded, whereas others were retrospective accounts from the later eleventh and early twelfth centuries. They vary enormously in scope, detail, and accuracy, from the fulsome (and often salacious) early-twelfth-century narratives of Orderic Vitalis and William of Malmesbury to accounts such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , which at times is so concise that the events of an entire year are covered by a single sentence.

The major chroniclers all drew upon a common pool of earlier sources, either quoting them verbatim or embellishing them with their own interpretations. Thus arose a form of historiographical telephone game, in which fact intermingled with fiction, real events with legend. The chroniclers also often wrote their histories as morality tales rather than strictly factual accounts. Although he claimed that each generation had a duty to keep a truthful record for the glory of God, Orderic Vitalis also firmly believed that history provided a record of events that was full of moral examples profitable to future generations: Everyone should daily grow in knowledge of how he ought to live, and follow the noble examples of famous men now dead to the best of his ability.

Next page

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION