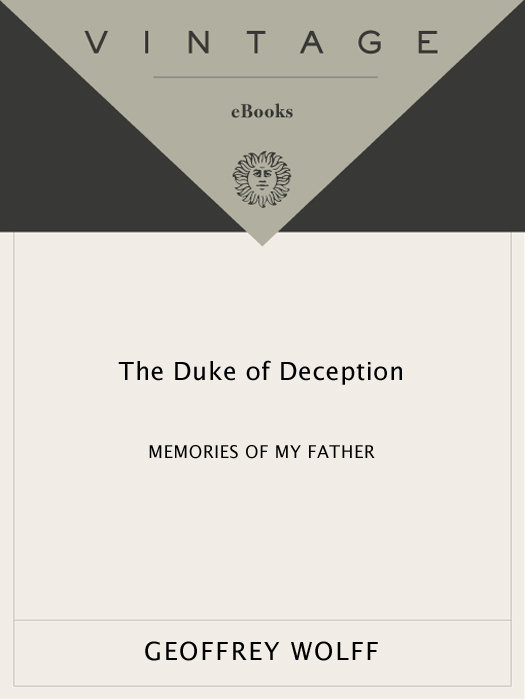

F IRST V INTAGE B OOKS E DITION , F EBRUARY 1990

Copyright 1979 by Geoffrey Wolff

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in hardcover, by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1979.

Library of Congress-in-Publication Data

Wolff, Geoffrey, 1937

The Duke of deception: memories of my father/Geoffrey Wolff.1st

Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-78447-6

1. Wolff, Geoffrey, 1937- BiographyYouth. 2. Wolff, Arthur Samuels, 1907 . 3. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. 4. Fathers and sonsUnited StatesBiography. 5. Impostors and impostureUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

[PS3573.053Z463 1990]

813.54dc20 89-40437

[B]

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

The excerpt from Certain Half-Deserted Streets by Geoffrey Wolff was originally printed in The Nassau Literary Review.

The material from Bad Debts by Geoffrey Wolff was first published by Simon & Schuster.

Copyright 1969 by Geoffrey Wolff.

Manufactured in the United States of America

79B86

v3.1_r1

This story is for

Justin and Nicholas

I wish to acknowledge the generous

help given to me during the writing

of this book by the John Simon Guggenheim

Memorial Foundation.

G. W.

Contents

Opening the Door

O N a sunny day in a sunny humor I could sometimes think of death as mere gossip, the ugly rumor behind that locked door over there. This was such a day, the last of July at Narragansett on the Rhode Island shore.

My wifes grandmother was a figure of legend in Rhode Island, a tenacious grandam near ninety with a classic New Englanders hooked and broken beak, six feet tall in her low-heeled, sensible shoes. A short time ago she had begun a career as a writer; this had brought her satisfaction and some small local celebrity. She spent her summers in Narragansett surrounded by the houses of her five children and by numberless cousins and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. One of these, my son Nicholas, not quite four, had just left for a ride with her. As old as she was she liked to drive short distances in her black Ford sedan, but she maintained a lively regard for her survival, and had cinched in her seat belt, tight.

Nicholass little brother Justin was with his mother at the beach. I was with my wifes brother-in-law on a friends shaded terrace. Kays house was old and shingled, impeccably neglected. It was almost possible to disbelieve in death that day, to put out of mind a sons unbuckled seat belt and the power of surf at the waters edge. I looked past trimmed hedges at the rich lawn; beyond the lawn a shelf of clean rocks angled to the sea. Sitting in an overstuffed wicker chair, gossiping with Kay and a couple of her seven children, protected from the sun, glancing at sailboats beating out to Block Island, listening to bees hum, smelling roses and fresh-cut grass, I felt drowsy, off-guard.

We had been drinking rum. Not too much, but enough; our voices were pitched low. Usually the house was loud with laughter and recorded musicall those children, after allbut this was a subdued moment. We were drinking black rum with tonic and lime; I remember chewing the limes tart flesh.

In my memory now, as in some melodrama, I hear the phone ring, but I didnt hear it then. The phone in that house seemed always to be ringing. My wifes brother-in-law John was called to the telephone; I guessed it was my wifes sister, fetching us home to our mother-in-laws. We always lingered too long with Kay.

John returned to the terrace. He stood thirty feet from where I sat supporting my drink on my shirt. I remember the icy feel of the glass against my chest. John was smirking, shifting from one foot to the other. John was a man to stand still, with fixed serenity, and my chest cramped. As I stared down the terrace at him, Kay and her children quit talking, and Johns cheeks began to dance. I looked at the widow Kay, she looked away, and I knew what I knew. I walked down that terrace to learn which of my boys was dead.

Justin was as sturdy as a fireplug: he once ate an orange-juice glass down to its stem; it didnt seem to trouble him. Another time was different: Running across a meadow he tripped, gave a choked cry, nothing out of the way. We walked toward him casually, paying no attention. We were annoyed to find him face foward in the mud. His mother said, Get up, but he didnt. He liked to tease us. I rolled him over, and his face was gray patched with pale green. His eyes had rolled back in his head: His brother began to cry; he had understood before we had, and his rage was awful. I tried to breathe life into my son, but in my clumsiness I neglected to pinch shut his nose. I blew and wept into his mouth, and tried to pry it open wider, just to do something, but mostly I wept on his face. My wife shouted at no one to call a doctor, but she knew it was useless. He was dead, any fool could see, and we didnt know why. Then he opened his eyes, went stiff with fear, began to cry. And upon the stroke of our deliverance I began to tremble. We are naked, all of us, I know, and it is cold. But Justin, it seemed then, was invulnerable.

So it was Nicholas.

John said: Your father is dead.

And I said: Thank God.

John recoiled from my words. I heard someone behind me gasp. The words did not then strike a blow above my heart, but later they did, and there was no calling them back, there is no calling them back now. All I can do now is try to tell what they meant.

1

I LISTEN for my father and I hear a stammer. This was explosive and unashamed, not a choking on words but a spray of words. His speech was headlong, edgy, breathless: there was neither room in his mouth nor time in the day to contain what he burned to utter. I have a remnant of that stammer, and I wish I did not; I stammer and blush, my father would stammer and grin. He depended on a listeners good will. My father depended excessively upon peoples good will.

As he spoke straight at you, so did he look at you. He could stare down anyone, though this was a gift he rarely practiced. To me, everything about him seemed outsized. Doing a school report on the Easter Islanders I found in an encyclopedia pictures of their huge sculptures, and there he was, massive head and nose, nothing subtle or delicate. He was in fact (and how diminishing those words, in fact, look to me now) an inch or two above six feet, full bodied, a man who lumbered from here to there with deliberation. When I was a child I noticed that people were respectful of the cubic feet my father occupied; later I understood that I had confused respect with resentment.

I recollect things, a gentlemans accessories, deceptively simple fabrications of silver and burnished nickel, of brushed Swedish stainless, of silk and soft wool and brown leather. I remember his shoes, so meticulously selected and cared for and used, thin-soled, with cracked uppers, older than I was or could ever be, shining dully and from the depths. Just a pair of shoes? No: I knew before I knew any other complicated thing that for my father there was nothing he possessed that was just something. His pocket watch was not just a timepiece, it was a miraculous instrument with a hinged front and a representation on its back of porcelain ducks rising from a birch-girt porcelain pond. It struck the hour unassertively, musically, like a silver tine touched to a crystal glass, no hurry, you might like to know its noon.