CONTENTS

Guide

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother,

Mary Jean Wood (ne Thomas). I just wish youd lived

to meet my wife, Mary-Ann, and your grandchildren,

Brax and Gordy. They would have loved you so much.

CONTENTS

The walls were pink and were crowding in on me. There was nothing in the space except a bench with a blanket, and a stainless steel toilet. The door had a small hole through which, every now and then, an eye would peer at me. Then the eye would disappear and Id be alone again.

I was numbed by the drugs I had taken earlier that fateful day, but not so numb that I couldnt remember the events in detail, and not so numb that I couldnt feel the first, panicky stirrings of withdrawal. Every addict is prone to the gnawing imperative of their cravings. For me, as for most addicts, drugs were an escape from reality. I had never needed the means to escape reality more than I needed them now. But part of that inexorable reality was the knowledge there would be no escape, physical or mental.

From time to time, panic or restlessness would drive me to my feet, and I would pace from wall to wall: one, two, three paces, turn around; one, two, three paces back. Experiencing no relief, I would curl up on the bench again.

I lay there, balled up, feeling trapped, buffeted by waves of sick realisation. Everyone who has ever made a major mistake in their lives and thats everyone knows the feeling when you suddenly become conscious of the terrible momentum of time, and how it cant be halted, let alone reversed.

Sometime after midnight, there was a clatter of keys in the lock.

Someone here to see you, the cop said.

I was handcuffed and led to an interview room. Sitting there on one side of the cheap Formica table, his eyes downcast and his shoulders hunched, was my father. He looked up as I entered, handcuffed and wearing the white paper overalls they give you when they take your clothes for forensic analysis. I slumped into the chair opposite him, and the cop took up a position next to the door.

What happened? Dad asked.

I didnt know how to answer. I wanted to tell him that whatever he had heard, it wasnt true. Or I wanted to tell him that it hadnt happened the way the police had likely told him it had. I wanted to say it wasnt my fault. I wanted to say sorry, to apologise for heaping another blow on top of the blow he had just suffered. I wanted to promise to make amends for the hurt and misery I could see in his eyes.

I dont think I said anything.

Something was itching above my eyebrow. I lifted my hand and scratched. I saw Dad glance at the cuffs. I felt something crusty where I was scratching. I looked at my fingernail and recognised dried blood beneath it. I saw other flecks of blood on my arms, and smears of blood on my wrists where I had tried to wash them. I felt sick.

I cant talk about it, I said, nodding in the direction of the cop. Not until Ive spoken to a lawyer.

When Dad had gone, my two older brothers came in, one at a time. I didnt have much to say to them, either, especially since it had occurred to me that they were only being let in to see me because the police thought I might open up to them. They wished me good luck. My older brother Jon gave me some prison advice: Keep your head down and dont stand out. Be a grey man; someone nobody notices.

Back in the cell, I realised thats what I had become: a grey man. All that promise and potential had been snuffed out, and I was just a husk. The faint excitement someone my age I was just 18 should feel in contemplating their many possible futures was gone. I knew what my future held: prison. I didnt know how long I would be spending there, but I knew it was going to be many years. It might as well have been the rest of my life.

*

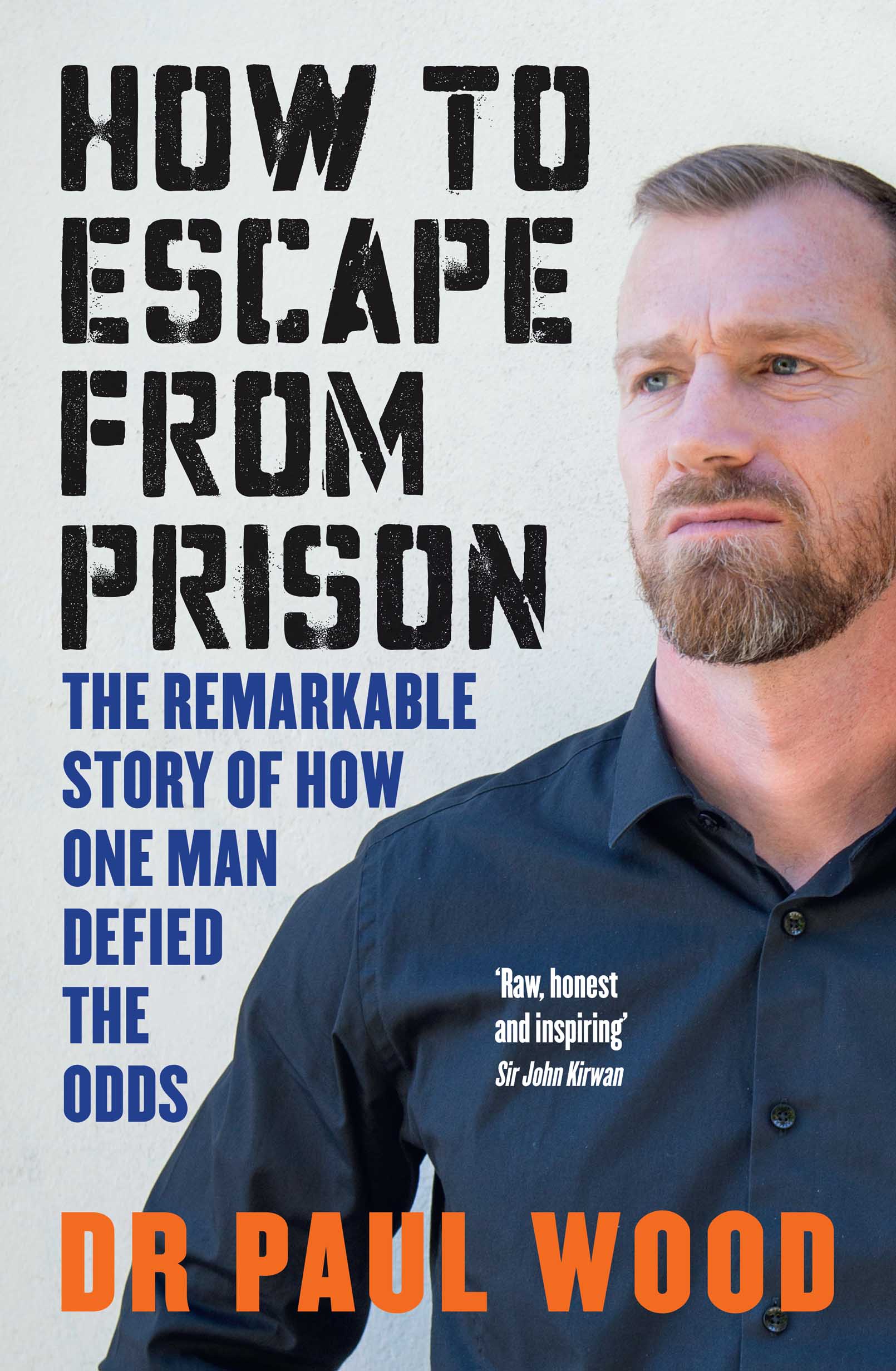

My name is Paul Wood, and I am a free man.

What I didnt know then but have come to realise is that I had been in prison for many years before I was ever locked up. Its one of the rich ironies of my lifes journey that I had to go to prison to learn how to be free. Now its my privilege to help others break out of their own prisons.

What I also came to realise while I was physically incarcerated was that most of the people I was inside with, and a hell of a lot of people walking around outside who assume theyre free, are locked up in mindsets that prevent them from living full, authentic lives. They are imprisoned by their beliefs about their limitations, about who they are supposed to be and what they are or arent supposed to feel. Thats as much of a waste of human potential as anything the criminal justice system has to offer.

What is a mental prison? Its a set of distorted or misguided beliefs that condition our view of ourselves and the choices available to us, that prevent us from seeing clearly (or at all) what we might achieve if we chose to live freely. As a teenager, I had a narrow, crippled, mistaken view of what it was to be a man. I chose to associate with people who held antisocial views and who reinforced my negative mindset. I dropped out of school, firmly believing I was immune to the benefits of education and was wasting my time there. I took drugs, because they helped me avoid experiencing the confusion and the emotional distress that I didnt think I was supposed to feel as a man. I was, in short, in prison. Other peoples prisons might differ from mine, but if they view the world and themselves through a clouded lens, then the freedom they imagine they have is an illusion, or at least a poor shadow of what it might be.

While most people would consider my life changed in the few short minutes during which I took another persons life, it didnt, really. Prison suited the kind of person I thought I was. I was surrounded by relentless negativity. People in there shared my own, unarticulated view of myself: that I was worthless and belonged in a place like the one in which I found myself. I had no problem getting hold of the drugs I thought I needed to get through, minute by minute, day by day. Going to prison didnt alter my behaviour and it would never force me to change for the better. Choosing to change would have to come from me.

I was lucky, in so far as the opportunity to choose to make changes came when I had matured enough to recognise it, through a chance association with people who thought I had potential and the opportunity to better myself through education. But luck wasnt everything. There was a lot of hard work involved as well. I cant pretend I broke out of my mental prison through my own unaided efforts, but if Id waited for other people to rescue me, well, Id still be there.

In recent years, I have been using my own experience and my training in psychology to help people to perceive the architecture of the mental prisons in which they languish, and show them how to break out. I have been helping people realise that the stress and hardships we encounter in life just provide the resistance required for growth, and that such adversity is a challenge to be embraced if we really want to unlock our potential. This is what this book is all about, too.

Much of what I write here is a prison memoir. Much of it is based on an account of my experiences I wrote while still in prison, just before I was due to be released. Its been amusing and not a little unsettling to compare my current recollections of my time in prison with what I wrote when I was much nearer to events, and presumably recording them more accurately. This has been a lesson in what psychologists call the constructive power of memory.

Some of the material makes for rough reading, just as it was pretty tough to write. For those who have a low tolerance for such things, a warning: there is bad language. There seems to be no point in pretending prison is less foul than it is.

Next page