CAVALIER: A TALE OF CHIVALRY, PASSION AND GREAT HOUSES

COURTIERS: THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE GEORGIAN COURT

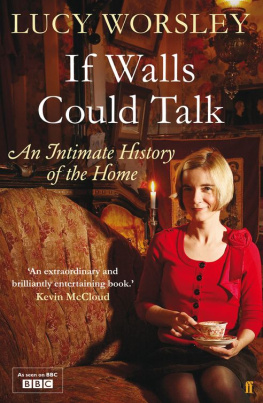

If Walls Could Talk

An Intimate History of the Home

LUCY WORSLEY

What I want to know is, in the Middle Ages, did they do anything for Housemaids Knee? What did they put in their hot baths after jousting?

H. G. Wells, Tono-Bungay, 1909

Contents

Why did the flushing toilet take two centuries to catch on? Why did strangers share their beds? And why did rich people fear fruit? These are the kinds of question I want to address in this intimate history of home life.

Moving through the four main rooms of a house bedroom, bathroom, living room and kitchen Ive explored what people actually did in bed, in the bath, at the table and at the stove. This has taken me from sauce-stirring to breastfeeding, teeth-cleaning to masturbation, getting dressed to getting married.

Along my way, I was intrigued to discover that bedrooms in the past were rather crowded, semi-public places, and that only in the nineteenth century did they become reserved purely for sleep and sex. The bathroom didnt even exist as a separate room until late in the Victorian age, and it surprised me that peoples attitudes towards personal hygiene, rather than technological innovation, determined the pace of its development. The living room emerged once people had the leisure time and spare money to spend in and on it, and Ive learned to think of it as a sort of stage-set where homeowners acted out an idealised version of their lives for the benefit of guests. Meanwhile, the story of the kitchen is also the story of food safety, transport, technology and gender relations. Once I realised this, I saw my own kitchen in an entirely new light.

There are lots of tiny, quirky and seemingly trivial details in this book, but through them I think we can chart great, overarching, revolutionary changes in society. A persons home makes an excellent starting point for assessing their time, place and life. Ive a great respect for things! says Madame Merle in Henry Jamess The Portrait of a Lady (1881). Were each of us made up of some cluster of appurtenances ones house, ones furniture, ones garments, the books one reads, the company one keeps these things are all expressive. Look around this room of yours and what do you see? asked John Ruskin in 1853. The answer, of course, is the same even today: you see yourself. Thats why, now as then, people lavish so much time, effort and money on their houses.

What else have I learned from writing this history of domestic life? Its been brought home to me that biology has always been destiny. Many major social upheavals come back, in the end, to little changes in the way that people think about and look after their bodies. I also think its interesting and instructive to find that the put-upon and down-and-out in the past werent always worse off than they are today. Industrialisation was a Bad Thing for many people; to be rich placed certain social obligations upon a person in the past that are now far from familiar. But this is a very old-fashioned history book in that generally, over the centuries, we see living conditions improve. Seemingly iron laws about behaviour eventually relax; amazing inventions remove problems at a stroke; there is hope for the future. My conclusion is that we have some distance yet to travel on this journey towards the good life, but that history can help to show us the way.

Most agreeably of all, I feel that Ive encountered some real people from the past, from all ranks in society, peasants to kings. If we reach out a hand across the centuries, we find that our ancestors are very much like us in the ways they lived, loved and died. Of all histories, wrote John Beadle in 1656, the history of mens lives is the most pleasant: such history can call back times, and give life to those that are dead.

In researching this book, Ive had two sources of extra help from beyond the walls of the library. Firstly, working at Historic Royal Palaces, as I do, I am surrounded by people whose job it is to bring the past back to life for our visitors. We talk about the topics covered here every day. Secondly, Ive had the privilege of presenting a BBC TV series on the history of the home. For that project I tried out for myself many of the processes and rituals described here. I blackened a Victorian kitchen range, lugged the hot water to fill an unplumbed bathtub, ignited a gas streetlight, waded through nineteenth-century sewers, slept in a Tudor bed, drank a Georgian medicine made out of seawater, coaxed a dog into turning a roasting-spit, and even used urine as a stainremover. Each time we recreated some lost part of domestic life I learned something new about why and how houses developed.

Many of these humdrum tasks were so familiar to people in the past that they were hardly worth thinking about. I was talking about ideals, nobility, principles, cries one of the characters in Marilyn Frenchs classic feminist novel The Womens Room (1978). Why do you always have to bring us down to the level of the mundane, the ordinary, the stinking, f---ing refrigerator? But I would argue that every single object in your home has its own important story to tell. Your relationship with your refrigerator reveals a great deal about who you really are. Is it full or empty? Do you share it? Clean it yourself? Have someone to clean it for you? The answers to these questions define your place in the world. As Dr Johnson put it:

Sir, there is nothing too little for so little a creature as man. It is by studying little things that we attain the great knowledge of having as little misery and as much happiness as possible.

PART ONE

An Intimate History of the Bedroom

Nearly a third of history is missing. You very rarely hear about the hours when people were asleep, or on the borders of it, and its worth trying to fill that gap.

Today your bedroom is the backstage area where you prepare for your performance in the theatre of the world. For us its a private place, and its rude to barge into someone elses bedroom without knocking.

But this is a relatively new phenomenon. Medieval people didnt have special rooms for sleeping. They simply had a living space in which they happened to rest or eat, or read, or party and they used the same room for everything. The idea that you might sleep by yourself, in your own bed, in your own separate room, is really rather modern.

The functions of bedroom and living room eventually became separate, yet the bedroom remained a social space for a surprisingly long time. Guests were received in bedrooms as a mark of favour, courtship and marriage were played out here, and even childbirth was for centuries a communal experience. Only in the nineteenth century did the bedroom become secluded, set aside for sleep, sex, birth and death. In the twentieth century, even the last two left the bedroom behind and went off to the hospital.

Because the room in which you slept was so much more than just a place of rest, the history of the bedroom is a vital strand in the history of society itself.

There are few nicer things than sitting up in bed, drinking strong tea, and reading.

Alan Clark, 27 January 1977

Once upon a time, lifes great questions were: would you be warm tonight and would you get something to eat? Under these circumstances, the central great hall of a medieval house was a wonderful place to be: safe, even if smoky, stinking and crowded. Perhaps its floor was made only of earth, but no one cared if the hall was full of company, warmth and food. Many people, then, were glad to doss down here. At night the medieval great hall became a bedroom.

Next page