To Kersti Worsley

Contents

6 November 1535

Elizabeth is twelve

Id always known that my adult life would begin once I was twelve. And that this would mean marriage.

Aunt Margaret had been working hard to prepare me.

Duty, Elizabeth, she used to say, thumping her walking cane down with every word, with every step. It is your duty to be a good daughter and, when your father has arranged a suitable alliance, it is your duty to be an obliging wife. You must be ready.

Duty. A word as heavy as the thickest featherbed.

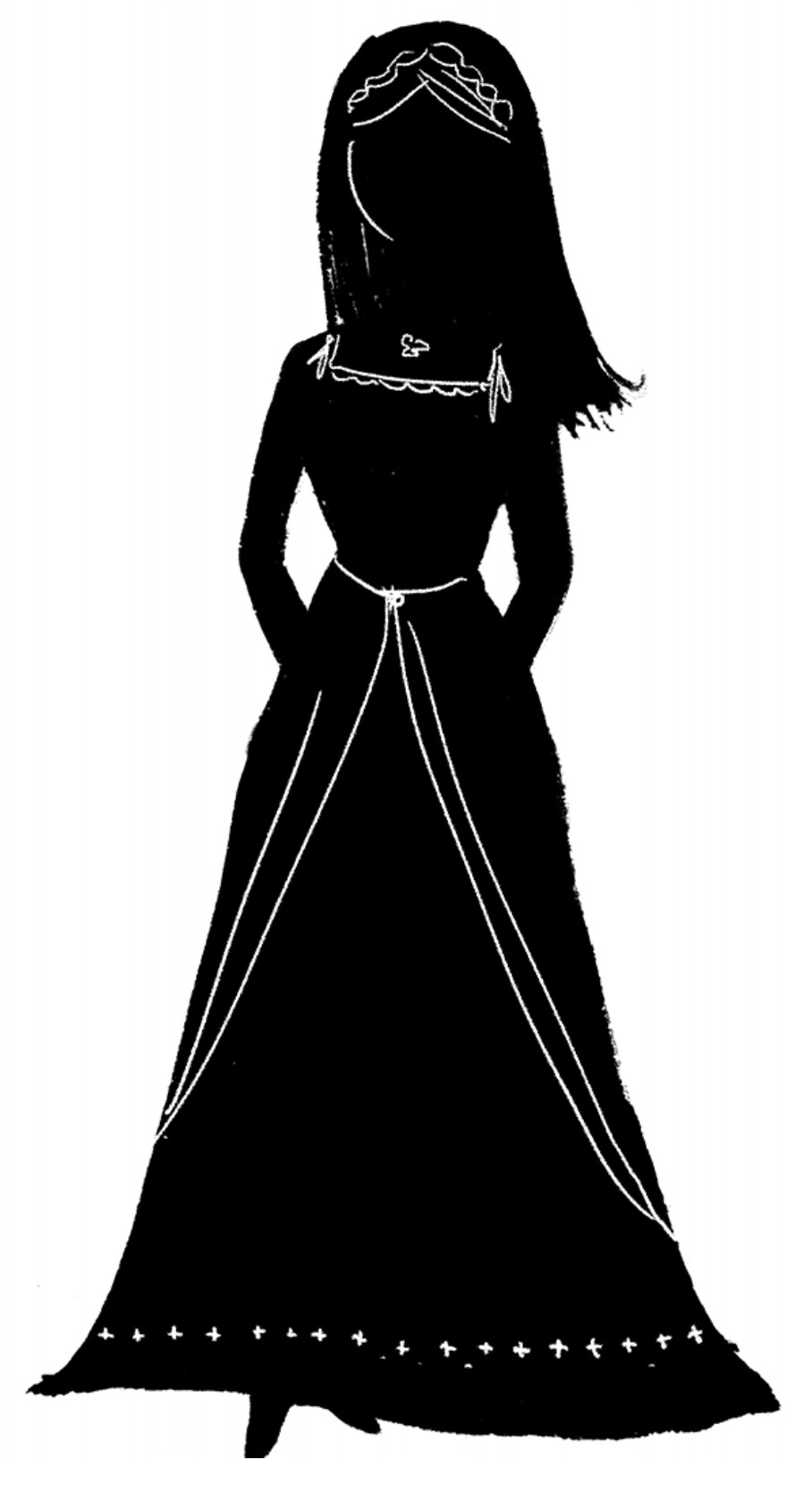

I would often lie in bed, wondering about my future husband. A prince? A knight? A duke? A stable boy? Of course, the last was a wicked fancy. Aunt Margaret often said I had the devil in me on account of my wild nature and red hair. I was inordinately proud of my long, red hair. Id heard it was the same colour as the kings own and that of his daughter, the Princess Elizabeth. I wondered if they were plagued like me with blotchy freckles across my rather beaky nose.

Of course youre not a beauty, Aunt Margaret used to say, but its the bloodline that counts. Our family is one of the oldest in Derbyshire. So naturally I couldnt marry anyone I wanted. My father would make me a match into a family at least equal to ours in dignity and antiquity.

It was all very well to mull over whether I would rather be a princess or a duchess while safely tucked up in bed. But when Henny, my nurse, shook me awake on the November morning of my twelfth birthday, goose pimples spread all over my skin even before she had pulled back the slightly mangy fur coverlet.

Hurry up, child, Henny said. Your father wishes to speak to you.

I began to yawn and stretch myself, but suddenly the thought of the cold was banished from my mind. Henny! I said urgently. Have you forgotten what day it is?

Its Tuesday, my love, she said, now with her back to me, pulling down the blanket we pegged over the window to keep out the worst of the draught at night.

Henny!

Her shoulders twitched. An instant too late I realised that of course she knew perfectly well that today was my birthday. She turned round with a broad smile.

Gah! I said, making a fist and tugging at my long braid. She had caught me out. But I could not help grinning back. A new thought struck me as I tossed my messy plait back over my shoulder. Henny, does my father want to give me a present?

I dont think so, not at this hour. My father wasnt very good at remembering things like presents anyway. But Henny could be relied upon to have got me a sugar mouse or a new pair of velvet slippers.

Well, what then?

What a question! As if his lordship would discuss such a thing with me.

I laughed. Oh, Henny, he knows youre one of our family!

Nonsense, child. Now hurry. She turned away quickly as if to stir up the miserable little fire in our great, gaping stone hearth. But she was too late and Id detected that she was beaming.

Henny was my nurse, but really I was far too grown-up to need one. I called her instead my tiring woman, who helped me to get dressed or attired. Unfortunately Henny herself kept forgetting about her new status, and when I reminded her, she would usually say that I was the tiring one, and that I quite wore her out with my questions, my constant demands for new stories (not that one, we had it last week) and the mess that I made of my clothes.

Despite Hennys efforts with the fire, it was so cold that the tiny glass panes of my window were beaded with moisture. I snatched my toes back from the freezing floor and burrowed round in my bed for a pair of woollen stockings I had taken off last night. It had been too chilly to get out of my bed to return them to their proper place in the chest. As I threw off the coverlet and the rather threadbare linen sheets, Henny handed me my heavy velvet robe with the fur trim. It was a sumptuous garment that was sadly disfigured by a great stain down the front. Nothing in our house, Stoneton a snake of ancient grey towers running along the top of a hill was quite as grand as it seemed at first.

I did up my robe as quickly as I could. Catching a glimpse of freezing fog outside the window, I grabbed a shawl to go on top. I had hardly finished swathing myself in fabric when Henny prodded me towards the door. All right, all right! I grumbled. There was never usually this level of urgency in our early morning routine, even on a birthday.

Henny shooed me down the uneven floor of the long gallery, and we passed by the door to the best bedchamber. It always stood empty, being saved for important guests who never came. Next to it hung a tapestry showing a forest in full leaf, which actually concealed a tiny little hidden door. This led to the sally port, the secret staircase, and my favourite part of our house. The winding steps led upwards to the walkway that led around the high defensive walls, and downwards, they took you to the hidden entrance from the garden. I would often steal away to the secret stairs myself, looking for a place to hide when my father was in a bad temper. Henny spotted my hesitation by the secret door.

Youre not in trouble this morning, you know, she said, giving my shoulder a little squeeze.

I shook her off impatiently. I quite often was in trouble, for making a smart answer or failing to keep my things tidy, and then the sally port became my refuge. Running down those stairs, I would pretend I was a knight like Prince Arthur of old, clanking in my spurs, ready to repel invaders. Running up them, I liked to reach the wall walk, and then climb to the top of our highest tower, imagining that all the land in every direction was my own.

It would have been, once upon a time, but the farms had been sold and forests felled. Indeed, in the middle of what should have been our finest hunting park, a trembling column of grey smoke arose from the lead smelting concern that my father had set up with capital he could ill afford, and which had yet to produce any of the money we desperately needed.

Aunt Margaret constantly complained that we never had the kind of feasts and balls that she and my father had enjoyed in their youth. This was because of the Great Forfeit, which had been paid by my fathers long-dead elder brother, the traitor Baron Camperdowne. But if I ever asked about him, she told me for the hundredth time that a maid should be seen and not heard.

The early hour, the unexpected summons and Hennys brusque kindness gave me a disturbing sense that something important was about to happen. I felt a little hollow inside. It had been a long time since last nights pottage and bread, and that had hardly been a feast. I dug my fingers into my palms to keep my hands from twitching with nerves. At Hennys nod, I knocked on the door to the Great Chamber.

Inside were huge windows cut into walls hung with faded tapestries. Along one side of the room ran black-stained wooden panelling, from which the white painted faces of our ancestors peered down. I knew that they were watching and judging me. My grandfather was there in the line-up, and my mother, but one portrait was missing. There was a blank patch in the corner where Aunt Margaret had had a picture removed. My traitor uncle.

My father was standing at the window when I entered, his warm breath misting the glass.

His name was Lord Anthony Camperdowne, and he was the Baron of Stone. It was because he had no sons that Aunt Margaret was constantly drumming it into me that one day I would have to take on the responsibility for our great grey house of Stoneton. I knew that it was a very old and very important house, and that our family was very old and important too. But my father did not look important. He was a thin, wiry, short man, with a pointed little ginger beard and baggy breeches. He sometimes reminded me of a fox, his head constantly swivelling round in search of danger or opportunity. Now he swivelled it towards me and smiled.

Next page