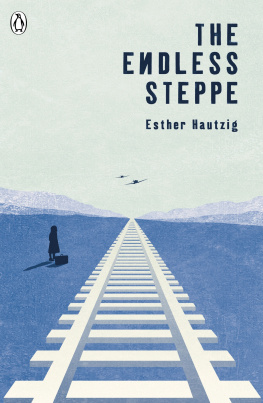

PENGUIN BOOKS

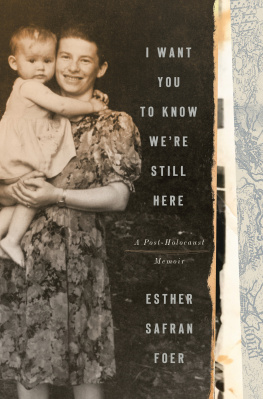

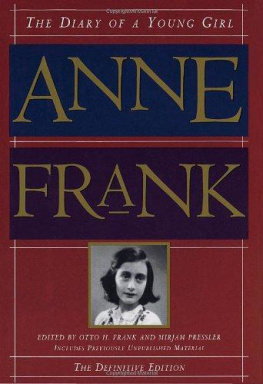

Esther Hautzig was born in Eastern Poland (in what is now Vilnius, Lithuania) in October, 1930. When the region was conquered by Soviet troops in 1941, Esther, her parents and her grandparents were uprooted and exiled to Siberia where they spent the next five years in forced labour camps. The family returned home after the war and in 1947 Esther left to go to the USA as a student. Her acclaimed novel The Endless Steppe was inspired by her gruelling wartime experiences. She was married to a concert pianist and had two children. Esther died in 2009.

About the Book

Esther Rudomin was ten years old when, in 1941, she and her family were arrested by the Russians for being capitalists and transported to the endless steppe of Siberia. This is the very moving true story of the next five years spent in exile, of how the Rudomins kept their courage high, though they went barefoot and hungry.

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk

www.puffin.co.uk

www.ladybird.co.uk

First published in the United States of America 1968

Published in Great Britain by Hamish Hamilton 1969

First published in Puffin Books 1990

This edition published 2016

Copyright Esther Hautzig, 1968

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-38405-3

All correspondence to:

Penguin Books

Penguin Random House Childrens

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL

This story would not have been told

without the help of many, many people.

It is gratefully dedicated to all of them.

CHAPTER ONE

The morning it happened the end of my lovely world I did not water the lilac bush outside my fathers study.

The time was June 1941 and the place was Vilna, a city in the north-eastern corner of Poland. And I was ten years old and took it quite for granted that all over the globe people tended their gardens on such a morning as this. Wars and bombs stopped at the garden gates, happened on the far side of garden walls.

Our garden was the centre of my world, the place above all others where I wished to remain forever. The house we lived in was built around this garden, its red-tiled roof slanting towards it. It was a very large and dignified house with a white plaster faade. The people who lived in it were my people, my parents, my paternal grandparents, my aunts and my uncles and my cousins. My grandfather owned the house, my grandmother ruled the house; they lived rather majestically in their own apartment, and the rest of us lived in six separate apartments. Separate, but not exactly private. There were no locked doors; people were always rushing in and out of each others apartments to borrow things, to gossip, to boast a bit or complain a bit, or to tell the latest family joke. It was a great, exuberant, busy, loving family, and heaven for an only child. Behind the windows looking out on our garden there were no strangers, no enemies, no hidden danger.

Beyond the garden, beginning with the tree-lined avenue we lived on, was Vilna, my city. For the best view of Vilna one went to the top of Castle Hill, and I was always asking Miss Rachel, my governess, to take me there. Built along the banks of the river Wilja in a basin of green hills, Vilna has been called a woodland capital. It was a university town, a city of parks and white churches with gold and red towers built by Italian architects in an opulent baroque style, a city of lovely old houses hugging the hills and each other. It was a spirited and gay city for a child to grow up in.

From this hilltop I could make out the place where my familys business took up half a block, the synagogue we attended, the road that led to the idyllic lake country where we had our summer house. When I stood on this hilltop everything was just as it should be in this best of all possible worlds, my world.

And, down to the smallest detail, I would not have had any of it changed. What I ate for breakfast on school mornings was one buttered roll a soft roll, not a hard roll and one cup of cocoa; any attempt to alter this menu I regarded as a plot to poison me.

I would sit down to this breakfast at a round table in the dining room with my young parents or my beloved Miss Rachel. My Father called Tata, the Polish for papa was my most favourite person in the world, a secret I thought I ought to keep from Mama. Tata was gay and fun-loving and not only made jokes himself, but laughed at mine whether mine were funny or not.

Mama was gay, too, with an engaging talent for laughing over spilled milk, but at an early age I found out that she was a strong-minded lady who thought that one indulgent parent was quite enough for an only child. When I was four years old, she and I first locked horns. I had just begun to attend a progressive nursery school, and one morning, when I and a dozen or so other little girls were doing calisthenics on the floor, I made a shattering discovery. All legs had been swung back over heads, all toes were touching the floor, when, rolling my eyes from side to side, I saw that all the panties thus displayed were silk white, pink, blue, yellow silk, a gorgeous rainbow of silk panties, some even edged with lace except mine. Mine were white cotton, severely unadorned. I told Mama that this situation must be corrected immediately. She thought not. I said that if I could not wear silk panties I would not go to nursery school at all. Mama said: Very well. Dont go. I didnt go; I stayed home until it was time for me to go to grade school when I was seven.

And when it came to choosing the school, Mama decided it was character-building for a rich child to go to a school where there were children from all economic brackets. I went to the Sophia Markovna Gurewitz School, where I learned Yiddish and was introduced to the literature and culture of my people.

I loved school and I loved the order of my life. My days were planned with the precision of a railway timetable. On Mondays after school there were piano lessons; Tuesdays, dancing class; Wednesdays I went to the library and invariably argued with the librarian, who recommended childrens books when I wanted grown-up books, particularly mysteries and the more blood-curdling the better. On Thursdays my cousins and I had calisthenics with a muscular lady who drilled us as if we were candidates for the Prussian Army, which made us explode into giggles. And on Fridays I was allowed to help Mama and the cook prepare the Sabbath meals braid the challah, the ritual bread, and chop the noodles. On Fridays, the seven kitchens of our house would send forth the marvellous smells of seven Sabbath meals all alike the same breads, sponge cakes, chickens, and chicken soup.

But in 1939 Hitlers armies marched on Poland.

When the first bombs fell over Vilna I was terrified, of course. But we were lucky; no bombs fell in our garden. Our garden was invulnerable.