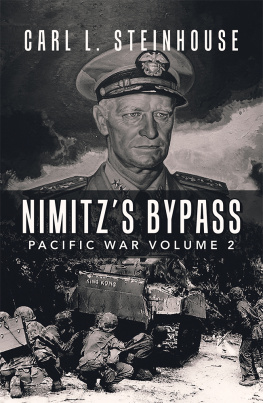

ADMIRAL NIMITZ

THE COMMANDER OF THE PACIFIC OCEAN THEATER

BRAYTON HARRIS

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

PREFACE

The sealike life itselfis a stern taskmaster. The best way to get along with either is to learn all you can, then do your best, and dont worryespecially about things over which you have no control.

Charles Henry Nimitz

Chester Nimitz has long been overshadowed by flamboyant World War II contemporaries, men who collected colorful nicknames like Bull or Howlin Mad. These men knew how to work the mediaand write memoirsto claim credit or settle scores. Nimitz had no nickname, left no memoir, and refused all requests from authors who wanted to help tell his story. He had commanded the 2 million men and 1000 ships that won the war in the Pacific. He felt that was legacy enough.

Admiral Nimitz: The Commander of the Pacific Ocean Theater is the story of an unsophisticated sixteen-year-old from rural Texas who wanted to go to West Point but ended up at the Naval Academy, and learned his profession, one job at a time. Thus, the book you are holding is more than a war story: it is a guided tour of a remarkable career, covering the six afloat commands Nimitz had in his first six years of commissioned serviceand his court-martial for running aground; his seminal work in developing diesel engines, underway refueling, and tactical formations; how he built the Pearl Harbor submarine base with borrowed World War I surplus materials; and how he set up one of the first Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) units in the nation. And how, as head of the Navys personnel bureau, he helped the fleet get ready for the coming war.

Most important, to fight that war, Nimitz developed an operating philosophy that allowed his fleet to win battles, often with forces smaller than those of the enemy. A hands-off commander, Nimitz did not smother subordinates with urgent directives. He would develop a plan, pick the right people to carry it through, let them know what he expectedthen get out of the way to let them do the job. He was not, however, isolated and remote, but made frequent visits to the battle zonesoften, before the battle was overto collect the assessments of his commanders and to encourage the war-fighting forces.

At the same time, he fought more subtle engagements. He was put in command of the Pacific Fleet by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, not by the uniformed leaders of the Navy. His own immediate superiors did not know him very well, and for most of the first year of the war they viewed him with suspicion, as just another political officer who gained stature from his connections, not skill and experience. Then, with that battle won and Nimitz fully in chargeand the war against the Japanese brought to an endhe had to fight both Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal and President Harry S. Truman to get the coveted career-topping job of CNO, chief of naval operations. Then he became embroiled in another war, over the size and shape of the armed forcesbeating back efforts to eliminate the Marine Corps and submerge naval aviation under the Air Force.

I knew Admiral Nimitz, in a manner of speaking. I had lunch with him a few times exactly fifty years ago when he was about the same age as I am now. I was a junior officer on my first shore duty, at the Naval Station Treasure Island, in San Francisco Bay. Nimitz, then living in the hills above Berkeley, would often come down to our officers club, where the manager was a longtime friend of his. Full disclosure: I dont remember a thing he said, I was too busy telling him all about me. I hope this modest effort to tell his story will atone for the arrogance of youth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Admiral Nimitzs daughter Catherine (Kate) Lay and grandson Chester Nimitz Lay have been most generous in sharing family archives and stories, and in reviewing my text for egregious errors.

When some of my friends heard about this project, they passed the word to some of their friends, thus enlarging the circle of people who have directly contributed comments, suggestions, and encouragement. First, staffers at the Naval War College: Evelyn Cherpak, Donald Chisholm, Carla McCarthy, and Douglas Smith. Then, fellow authors and former associates who had something to offer: Brent Baker, Eric Berryman, Ralph Blanchard, Kenneth J. Braithwaite II, Elliot Carlson, Bruce Cole, Robert Durand, Dan Ford, George Gillett, George Kolbenshlag, Bob Lewis, John Lundstrom, Jack Mayo, Jerry Miller, Philip Russell, John Shackelton, Michael Sherman, Paul Stillwell, and Bill Thompson.

Finally, thanks to my agent, Joe Vallely, and the Palgrave Macmillan editorial staffLaura Lancaster, Luba Ostashevsky, Alessandra Bastagli, and Victoria Walliswithout whom there would be no book.

CHAPTER ONE

TEXAS

Let us begin, at the beginning. Chester William Nimitz was born February 24, 1885, in the German-American settlement of Fredericksburg, Texas. He could claim a maritime heritage of sortsboth his grandfather and greatgrandfather had gone to sea. For his great-grandfather, it was a full-time job; his grandfather Charles Henry Nimitzs sea time was limited to perhaps one cruise as a teenager, yet for most of his adult life he was known as Captain Nimitz. This was a military not maritime rank that came from his role as organizer of a Civil Warera volunteer militia in Texas.

Charles Henry was the most influential person in young Chesters life. One of the founders of Fredericksburg, which he and a small group of settlers built from scratch in 1846, Charles Henry was a classic entrepreneur. He set up a hotel in an eight-room sun-dried-brick building, which over time grew to offer forty-five guest rooms, a dining hall, casino, bar, brewery, bathhouse, and a combination ballroom and theatre. And, over time, the ever-expanding building came to resemble a beached steamshipcomplete with a mast for the flag and a crows nest for looking out over the hills. With a bit of enlightened marketing, it became known as Captain Nimitz Steamboat Hotel. In its heyday, the Nimitz was the last commercial hotel between the Gulf Coast and San Diego and played host to such guests as Colonel Robert E. Lee, General Philip Sheridan, and the author O. Henry, who used the hotel as the backdrop for a short story.

Charles Henry had twelve children; one son, Chester Bernard, was never really well, perhaps a combination of rheumatic fever and a congenital weakness of the lungs. Chester Bernard thought that working in the great outdoors as a cowboy, moving large herds of cows from Texas to Nebraska, would be curative. It was not, and five months after he married Anna Henke, the daughter of a cattle rancher, Chester Bernard died. Anna was pregnant with their son. She named him after his father.

Anna and baby Chester moved into her father-in-laws hotel where she worked in the kitchen. Chester grew up as a scrappy kid. His friends all had fathers, he did not. His friends enjoyed a lot of playtime, he was often stuck helping his mother in the kitchen. His light-blond hair triggered the nickname Cottontop, which he hated so much so early in life that he once dumped a pot of green paint on his head in a that-will-show-em! sort of move. His mother had to shave his head. Quick to anger, he got into fights with kids at school who teased or bullied him. He seems to have been pretty good at it, at least, according to relatives telling tales some seventy years after the fact, who credited him with taking on and defeating two at a time. Somewhere along the way he decided that fighting was not the best way to solve problems and learned to control his temper. Most of the time.

Next page