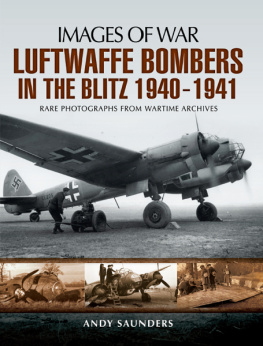

The Second World War would be a war in which civilian populations across Europe would be primary targets. As such, two factors dominated Britains preparation for the European war that seemed increasingly likely as the 1930s progressed: aerial warfare and the use of poison gas. Planning focused on civil defence, a term used more and more throughout that decade.

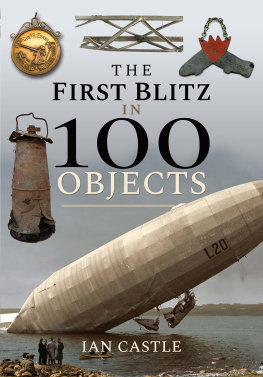

Airships and, later, aeroplanes had dropped bombs on civilian populations across the country during the First World War, killing over 1,400 people in just over 100 raids. The technology of aerial flight in particular had advanced dramatically in the twenty years since the end of that conflict. This would have an impact on military tactics as aeroplanes travelling at high speed replaced airships.

In 1924, the British government set up the Committee for Imperial Defence, which established an ARP (Air Raid Precautions) subcommittee to look at the organisation for war, including Civil Defence, home defence, censorship and emergency war legislation. This subcommittee met secretly for nine years, discussing ways of warning the population of air raids, preventing damage through such measures as restricting lighting (the blackout), gas masks, repairing damage and dealing with casualties.

In 1933, the year Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, the subcommittee set out detailed plans for ARP services to be organised through local authorities. By 1935, when the ARP Department of the Home Office was set up, these local authorities had been briefed on their responsibilities: the scheme would mean forming services to provide first aid, to deal with poison gas attacks and to rescue civilians caught in air raids. In that year, Hitler announced that Germany would re-establish her air force and introduce military conscription both of which were in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War.

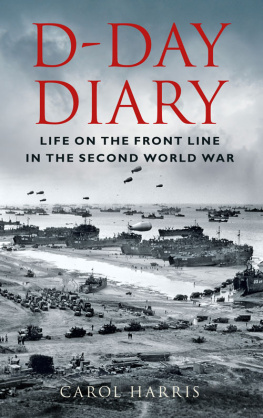

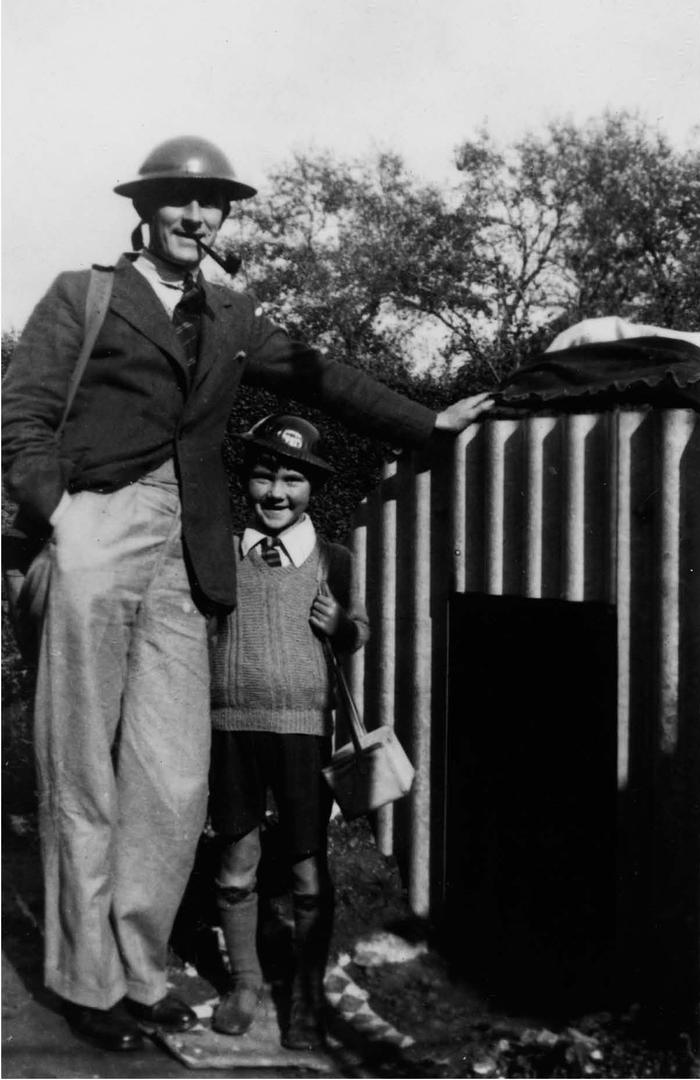

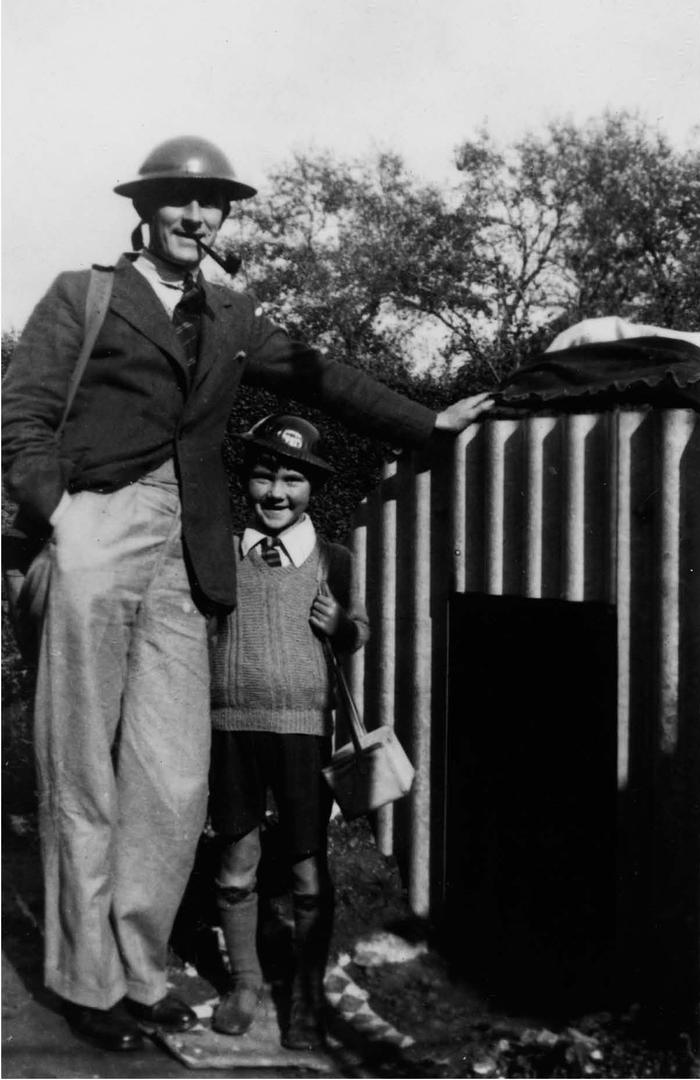

Pictured by the family Anderson shelter, these two still carry their gas masks which suggests it is early in the war. Anderson shelters consisted of curved sheets of aluminium buried several feet into the ground. Earth was shovelled on the top of the shelter ideally deep enough to plant flowers and vegetables.

The first official broadcast on ARP services went out in January 1937 on the BBC. Debate had raged for some time as to the appropriate response to the threat of air raids. Some felt that the introduction of such a scheme was itself provocative. In the British Medical Journal, doctors argued whether they should co-operate at all. Across the country local authorities reflected this ambivalence. Some services were well organised with volunteers training to deal with the effects; most were not. In general, ARP was regarded as something of a joke.

Attitudes changed markedly in 1937, when cinemas newsreels showed the impact of the aerial bombardment of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Guernica was attacked on 26 April of that year by the German and Italian air forces in support of the fascist or nationalist side. Dr Duncan Leys letter to the British Medical Journal, written a few weeks later, sums up the feeling that Britain was woefully unprepared for the onslaught that was to come:

22nd May 1937

SIR, It is no longer correct, I find, to think of our work as one of healing. I learn from the Home Office Instructor on Air Raid Precautions in the Birmingham area that my duties in the next war are to aid the police in preventing panic, to reassure the gas casualties, to get it into peoples heads that whether they have gas-proofed rooms or not the important thing is for them to be under cover in their own houses, that the whole danger of gas attacks lies in the lowering of national morale, and that the medical profession, as a group of persons who can speak with authority, is to maintain that morale, in which function the Home Office considers them of only less importance than the police.

These actual quotations from a lecture are no misrepresentation of the general tenor. Having heard pacificists [sic] maintain that the main object of the Governments air raid precautions scheme was a military one that is, to make panic or any mass protest against the continuation of war less likely, and that protection from death and injury in air raids on cities was only possible by the erection of bomb-proof shelters which the Government considered too expensive to contemplate I attended this official lecture, delivered by a doctor to other doctors, on the invitation of the British Medical Association in order to learn what attitude was taken by the Home Office officials themselves. I was prepared to hear the lecturer say that, with the Prime Minister, he acknowledged that nothing like protection to a city population was possible short of bomb-proof and gas-proof shelters constructed for the purpose, but that until the Government had made its plans, the possibility of sudden air attack on cities existed, and that the Air Raid Precautions Department offered some advice as better than none, that a few lives might be saved by such advice, and that he was there to tell us how we could help in this limited sense. Such an approach to the question would have had my full sympathy and co-operation.

The lecturer opened by assuring us that he had no connexion with the fighting services: the Air Raid Precautions Department had nothing warlike about it, and was intended purely for the passive protection of the civil population. He told us that it would require anything from a few inches to several feet of concrete to protect buildings from air raids, and that nobody had suggested that it was possible to protect the whole population in this way. He went on to describe how we might advise people to erect on scaffolding three layers of filled sandbags on their roofs, with two feet interval between the layers, to protect them from splinters from high explosives. No enemy, he continued, would use gas bombs only; high explosives would first be used to demolish important centres like railway stations, public buildings including hospitals, which would become too dangerous to be used for other purposes than as casualty clearing stations and generally to do as much damage to structure as possible. Thermite bombs would follow in thousands with the aim of starting a general conflagration in the city beyond the powers of the fire brigades to deal with. Gas would next be sent down by spray or bomb, and it was then that doctors and first-aid services would be needed to prevent panic, to reassure those affected, and to persuade people to remain in their houses.

A passing mention was made of the difficulties of protecting the aged and children and invalids, but respirators were a second line of defence and the main thing was that people should stay indoors. No mention was made of the impossibility for most working-class families of providing a room for gas-proofing (a room rendered uninhabitable because of boarded windows and blocked ventilators or chimney), and although the lecturer said that the modern bombing plane could aim accurately to within seventy-five yards no mention was made of the certainty that windows and gas-proofing would certainly be destroyed over a wide area surrounding the fall of a high-explosive torpedo.

No opportunity was given for questions or discussion, and one is therefore unable to say how far the audience of some thirty doctors accepted the role indicated to them of persuading their neighbours that the Air Raid Precautions Scheme could really save them and their children when it must be perfectly obvious to the meanest intelligence that it can do nothing of the sort, and that the whole apparatus of the scheme is designed to deceive people into thinking that it will. I am not accusing the lecturer of deception: he was painfully honest. It is obviously much more satisfactory, from a military point of view, that people should die quietly in their homes than that they should run about the streets and possibly mob Cabinet Ministers: they might even, fearing retaliation, try to persuade our own airmen from their efforts to destroy French, German, Italian, or Russian cities.