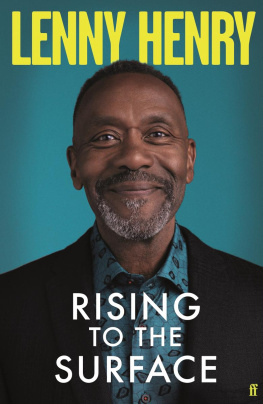

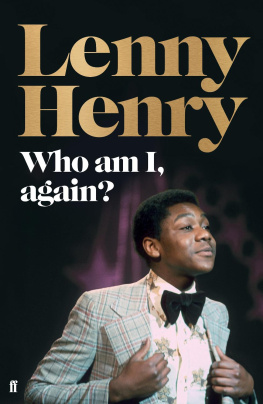

Now, 2019

Im in the back of a black cab heading from Westminster, going past Victoria Station. Rain-slicked scaffolding, Hamilton the musical, fast-food joints, commuters and an onslaught of targeted advertising that beggars belief. Londons brilliant.

I thought Id attempt a bit of context before we dive head-first into my story. The first thing to say is that this is only part of my story the early years. To create a memoir from where I am now would involve a massive amount of memory mining. I didnt keep a diary when I was a child, so assistance from the past is not particularly forthcoming.

In many respects I was a normal kid I loved playing and pretending. There were TV programmes called things like The Saint and The Champions and Man in a Suitcase, and I loved them all. When I walked to school in the morning, I was Simon Templar or Amos Burke or John Steed. These guys didnt look anything like me, but I wanted to be like them. In art classes, when I made a self-portrait of me as a secret agent or a kick-ass cop with super-powers, I invariably drew myself as a white guy, in a sharp suit and sporting a pointy quiff. That was my experience of what was on television all the time. Black people were usually the baddies or the trusty friend with a twinkle in his eye or the victim. I chose not to emulate those guys. I only wanted to be the cool-talking, martini-drinking, gun-toting hero who was usually white.

This was the early 1960s, so there were very few people of colour on TV. If we were ever spoken about on screen, it would usually be as the butt of a comedians joke. More often than not, we were a punchline. But as I reached my early teens in the early 1970s, things were beginning to change.

In the meantime, Im still in the cab, thinking about the way things were back then.

In terms of this book, I thought it would be worth talking a little about my siblings my fantastic brothers and sisters, Hylton, Seymour, Kay, Sharon and Paul because they are a route to my mother, Winnie, who passed away in 1998. Im also going to talk a lot about my three most prominent friends during my post-pubescent, most formative period: Greg, Mac and Tom. We called ourselves the Grazebrook Crew, after the road where Mac lived, and they remain a key part of my story.

Im going to discuss growing up and puberty and school and getting up on stage at the Queen Mary Ballroom (a dance venue at the top of Dudley Zoo. The animals watched us go in sober and come out drunk). I intend to talk about as much of my life as I feel can fit into this framework, which I reckon stretches from 1958 to 1980-ish. That takes us up to a crucial point in my development, and includes the first angry outbursts of punk and the related uprising of alternative comedy. Perhaps another book will take in marriage and Chef! and later versions of The Lenny Henry Show and Hollywood and the like. But right now, I want to focus on this quite tight time frame. It feels manageable.

Ive been communicating with my friends and family about the whole writing/memory-mining process. They all wanted to have their say, and I have referred to them when I thought it apposite. I do have a problem with dredging up old thoughts and memories, however. I find that sometimes things werent how you actually remembered them. You think it sort of happened like that, but theres bound to be a bit you dont quite remember; therell be the crystalline and honed dinner-party version of that story. But then theres the crushing moment when your mum or uncle or sister or mate tells you, It wasnt quite like that, or You didnt exactly say that and on and on and on. We reframe and re-edit our pasts: exam results change, our teachers become kinder or more ogre-ish, our sporting prowess more Olympian and our sexual exploits exhaustingly naughty, horny and relentless.

Theres another reason for not entirely spilling my internal organs onto the page: there are some things about my childhood that I genuinely dont know. The moments Im not sure of Ive tended to leave out like the least-liked Opal Fruit. The idea that memoirs are a time for settling old scores doesnt gain much traction with me either. My gut tells me that if I was too cowardly or hesitant to sort something out at the time, what good would it do to dredge up the moment again and cross-examine it in retrospect? When I do discuss things or events where I felt hard done by or misused, I hope Ive dealt with them fairly.

In On Writing, Stephen King compares Mary Karrs evocation of her childhood as an almost unbroken panorama with his sense of recall, which appears like a fogged-out landscape from which occasional memories appear like isolated trees. I know what King means here: for some of us, memories are sketched, ghostly things unreliable. The one phantom thread running through the forest of my story is Who am I? or Who should I be for the people around me? Who do they expect me to be? Son? Pal? Comedian? And so each time a new Lenny was needed, I jumped.

For the most part, then, this book is not an autobiography, but a biography. Because Im writing about someone I used to know.

Nelson Mandela once said, Forget the past. In many respects I think he was right. The past can appear to be this other country, this exalted place where you spent so much time and where so many things happened that were good or bad or painful, and its difficult to let go, but in the living of life there is forward movement and so you wind up letting go anyway, just by virtue of putting one foot after the other.

So while Im relatively happy to look back, right now Im in a cab moving forward and, when I reach where Im going, I will continue putting one foot in front of the other and then Ill jump.

MAMA

Before anything else, I remember Mama. She was the Jamaican Wonder Woman. Im being a bit facetious there were lots of women like my mama. She was of a particular stock, the kind of person who had worked very hard from a very young age. She had powerful hands, and if you were swiped or punched by either of them, you knew about it.

Mamas feet were large. As a child, I would try on her shoes. They were huge massive boats with heels and a buckle at the front. I would slide around in them pretending to be important, because, whether she wanted the title or not, Mama was the alpha in our family. Papa was tough and manly in appearance, but at home it was very clear who was in charge. Mama was just better equipped for the trials and tribulations of raising a large family in a semi-hostile environment.

Her legs were incredibly powerful. She had obviously spent many years walking the highways and byways of the Jamaican countryside. As a subsistence farmer and market trader she spent hour upon hour working in the fields and carrying straw baskets of fruit and veg to and from the market. Having seen some of these fields, highways and byways for myself, its clear that walking long distances was the norm for people like Mama and Papa. I now understand why walking was such a big part of her life here in the UK, where she would clock up miles trudging around Dudley and beyond.