To my partner in crime, Justin

Contents

Guide

At 3:45 a.m. on August 31, 1888, Mary Ann Polly Nichols was found dead in a London gatewayone of the first victims of Jack the Ripper. Just half an hour before, a policeman had walked by the gateway and found it empty. The murder must have occurred minutes before the body was discovered. So where was the killer now?

At first, police investigated those connected to Nicholsher ex-husband, for instance. But he had no motive. By now, he and Polly were living separate lives: he was caring for four of their five children near Old Kent Road in South London, and she was living as a prostitute in the East End. When three more victims were found the next monthall prostitutes and all with similar woundspolice knew the killer must be a stranger. Even today, stranger killings are difficult to solve. That was true more so then, when forensic science was in its infancy. The case poses the question: If the London detectives had had the tools that modern forensic scientists have, would Jack the Ripper be known today by his real name? Would some of his victims lives have been saved?

An 1888 issue of the Penny Illustrated Paper features sketches of one of Jack the Rippers victims and the suspected killer.

Perhaps. But the fact is, todays forensic science is built on innovations of the past. At the time of the Jack the Ripper murders, detectives did use several cutting-edge techniques, including crime scene photography and criminal profiling. Later, investigators would add to these, creating an arsenal of scientific tools that would help catch dangerous criminals. Techniques now include gathering trace evidence; testing bodies for poison; conducting autopsies; studying decomposed bodies; examining blood evidence; profiling criminals; testing DNA evidence; and analyzing bones, fingerprints, and markings on bullets.

Put simply, forensic science is the use of science to solve crimes. Though the following mysteries may seem to be ripped from the pages of crime novels, they are very real. Each describes the tragic takingand breakingof lives. Thats why forensic science is so important: it brings about justice for victims, peace of mind for communities, just punishment for the guilty, and freedom for the innocent.

Forensic science is far from perfect, however. As DNA testing became available, it helped to prove hundreds of prisoners innocent when, in many cases, less accurate forensic science methods such as bite mark analysis had been used to convict them in the first place. Forensic science disciplines are now being reviewed to determine their validity and to ensure that experts are clear about what forensic science can and cant tell us.

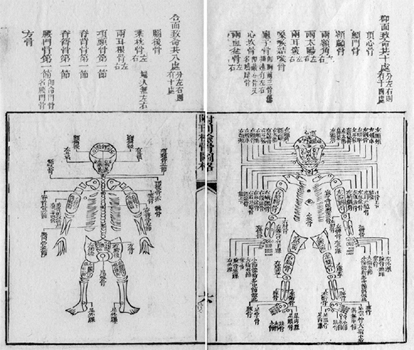

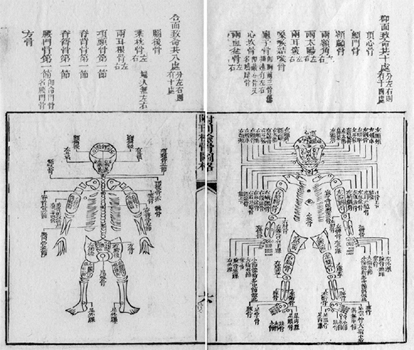

Soon after the dawn of DNA evidence, forensic science invaded pop culture. It was propelled by the popularity of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, which first aired in 2000 and unleashed a wave of similar crime shows. But forensic science is actually older than most people might think. In fact, its ancient. A Book of Criminal Cases, written around 270 CE, describes the work of Zhang Ju, a Chinese coroner who solved murders through the careful examination of victims bodies. In one case, he needed to determine whether a man had died in a fire or was murdered and then placed in the fire to cover up the crime. The coroner put two pigs in a fire, one alive and the other dead. Then he examined the pigs bodies. The pig that died in the fire had ashes in its mouth; the pig that was already dead didnt. The man didnt have ashes in his mouth either, proving to Zhang Ju that the victim must have been dead prior to the fire. Later in China, the book The Washing Away of Wrongs provided a textbook to other coroners. For instance, it described how to tell if a person had died from drowning or had been dumped in the water postmortem.

Anatomical diagrams from The Washing Away of Wrongs, a thirteenth-century Chinese crime-solving manual

Unfortunately, such ingenious forensic science didnt spread throughout the world. In England during the Middle Ages, crimes were examined by a crowner, so named because he was appointed by the crown, or king, and seized the property of criminals for the crown. In the case of murder, the crowner (which term gradually changed to the modern word coroner) was also charged with examining the body and investigating the crimebut to little avail, as he was neither a doctor nor a detective, but essentially a money collector. Crime wasnt investigated in any scientific way. The focus instead was on punishment. Whoever the crowner pointed a finger at was arrested and tortured or killed. Well into the 1800s, people were hanged publicly for murder, but also for minor offenses like pickpocketing. This was thought to deter crime, but even at the hangings, pickpocketing was rampant. It was clear that a new system was neededboth to eliminate cruel and unusual punishment and to ensure that when grave crimes did occur, the right people were punished. Crime needed to be fought not with fear but with science.

The Idle Prentice Executed at Tyburn, plate 11 from Industry and Idleness by William Hogarth, depicts the rampant pickpocketing that occurred at hangings in the 1700s.

Some of the first scientific tests related to murder cases were for poison, and arsenic in particular. Arsenic has been called inheritance powder and widow-maker for its popularity among murderers of the greedy variety. It was a favorite weapon because it made the death look like it was from natural causes. Before modern plumbing and safe food handling, serious stomach ailments like dysentery and typhoid fever were common, and even healthy people could suddenly die from these diseases. So if someone suffered from a bout of vomiting and diarrhea, it would likely be chalked up to illness. Even when suspicions arose, there were no tests for poison. All that changed with Mary Blandy, an Englishwoman accused of poisoning her own father in 1751.

Marys father, Francis Blandy, was seeking a nobleman for her to marry. To attract the best of suitors, Mr. Blandy started a rumor that his daughters dowry was 10,000 (more than $1 million today), though, in fact, he had little money. Mary had several men interested, all of whom her father deemed subpar. Finally, she met Captain William Henry Cranstoun and fell in love. Her father swooned, tooWilliam was the son of a lord and lady. Little did father or daughter know that the fine young gentleman would be their undoing.

In 1747, a year after the couple met, William proposed to Mary but also shared some troubling news. A Scottish woman was claiming to be his wife. Mary believed William when he assured her that it wasnt true, but she didnt tell her father. Mr. Blandy found out in a letter from Williams great-uncle. At first, Marys father believed Williams story, too, or went along with it anyway, apparently swayed by the young mans good name. Mr. Blandy was supposedly overheard saying that he hoped to one day be the grandfather of a lord. And so the engagement continuedfor a while. But when a year passed and William still hadnt straightened out his marital problems, Mr. Blandy grew impatient. He ordered Mary to break things off until William was free to marry. (In fact, he never would be. Unbeknownst to the Blandys, the courts had said that William was to remain married to his wife in Scotland.)