Table of Contents

To Bill, my beloved husband and tech support

Preface

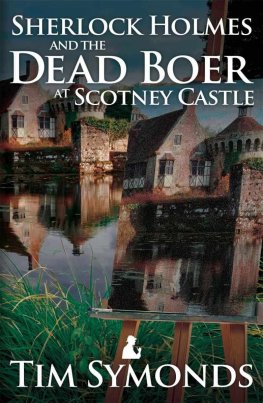

I first met Sherlock Holmes on Mosholu Parkway in the Bronx during the 1950s. At the time I was suffering through the torments of junior high school, my misery relieved only by the combined English and social studies class taught by a singularly humane teacher named Benjamin Weinstein.

It was Mr. Weinsteins engaging habit to invite his students to bring lunch to the park when the weather permitted. We would perch on logs and on the grass while he entertained us by reading aloud from work with which he felt we should be familiar. I always went.

He read with a fine but gentle authority. He did no funny voices. He did not perform strained pantomimes. He just provided a conduit that allowed the author to speak to us.

He read tales from Mark Twain and tales from Damon Run-yon. Toward the end of autumn, when it was growing cold and most of the leaves had fallen, he opened an unfamiliar book that had a dark blue cover and read:

On glancing over my notes of the seventy odd cases in which I have during the last eight years studied the methods of my friend Sherlock Holmes, I find many tragic, some comic, a large number merely strange, but none commonplace; for, working as he did rather for the love of his art than for the acquirement of wealth, he refused to associate himself with any investigation which did not tend towards the unusual, and even the fantastic.

It was the opening of The Adventure of the Speckled Band. The next day I was at the library to obtain the collected works.

Theres been a great deal written about the intense appeal of the Sherlock Holmes tales. I suspect it lies largely in the contrast between the emotional excitement of wild adventure and the reassuring intellectual control represented by Holmes. As I write this in 2005, when superstition threatens to seduce the civilized world with its dangerous embrace and science is dismissed in some quarters as merely an amoral discipline that humanity is free to abandon, a literary hero who possesses both intellect and a sense of ethics is particularly compelling.

Sherlock Holmes may have been fictional, but what we learn from him is very real. He tells us that science provides not simplistic answers but a rigorous method of formulating questions that may lead to answers. The figure of Holmes stands for human reason, tempered with a gift for friendship. (He may claim to be merely a brain, but he betrays an intense emotional core when he says to the villain in The Adventure of the Three Garridebs, If you had killed Watson, you would not have got out of this room alive.) Holmes has an incisive mind, a warm heart, and an artistic dimensionhe skillfully plays the violin. No wonder I and so may others are entranced.

Over the years I acquired rather more copies of the Canon than was sensible, and from time to time I would indulge myself, read a bit, and wonder if there was a way of incorporating my weakness for Holmes with my job of lecturing on the history of crime and forensic science. I did present a program called The Science of Sherlock Holmes: True Cases Solved by Conan Doyle, but that was about the author rather than the Great Detective. I kept toying with ideas, but basic sloth made it difficult to decide how to combine Holmes with criminal history.

And then one cold February afternoon while I was waiting for a loaf of bread to rise, I received an e-mail asking if I would be interested in writing a book that would use the Great Detectives adventures as a jumping-off point to discuss forensic science during the Victorian age. There could be chapters on anatomy, toxicology, blood chemistry, and a variety of other very complicated things. I could see at once that this endeavor would involve a prodigious amount of work.

It would mean contacting old friends who were specialists on fingerprinting, trace evidence, poisoning, and a number of other esoteric subjects and begging them for information. It would require detailed reading of old autopsy reports, crumbling newspapers, and lecture notes. It would mean convincing my husband that he would be delighted to spend weeks scanning fragile old pictures, formatting my messy typing, and compiling a bibliography that promised to be sizable. (My secretarial skills are sadly lacking.)

It would mean spending many hours poring over ancient medical tomes, dusty trial transcripts, and yellowing letters and papers, tracking down the details of crimes centuries old, isolated in my workroom with only hundreds of antiquarian books and Dr. Watson, our black Labrador Retriever, for company.

So of course I said yes.

Acknowledgments

Profound thanks to Mark Beneke, Ph.D., for details on insects; Robert A. Forde, for background on both the British legal system and the pronunciation of British names; Ernest D. Hamm, who can trace anything; Lee Jackson, for insight into Victorian life; Professor Erwin T. Jakab, for translations from the French; Professor Gernot Kocher, for information about Hans Gross; Sigmund Menchel, M.D., former chief medical examiner of Suffolk County, for much-needed help in analysis of the drowning at Tisza-Eszlar, as well as many other cases; James J. Maune, Esq., and William Nix, for information on the law; Andre A. Moenssens, Douglas Stripp Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Missouri at Kansas City, for background on legal photography; Stephen S. Power, my editor at John Wiley & Sons, for his patience and sensitivity and a really good idea; Marcia Samuels, for amazingly precise and considerate copyediting, and William R. Wagner, for both emotional and technical support. Without them this book would not exist. Any mistakes are mine.

I am deeply grateful to the members of the forensic world who over the years have, with great generosity, in different ways, helped me to learn. They include Jack Ballantyne, Ph.D.; Robert Baumann; Vincent Crispino, retired director of the Suffolk County Crime Laboratory; Leo Dal Cortivo, Ph.D., retired director of laboratories of the Suffolk County Office of the Medical Examiner; Joseph Davis, M.D., chief emeritus, Miami-Dade County Medical Examiner Department; Robert Golden; Charles Hirsch, M.D., former chief medical examiner of Suffolk County, currently chief medical examiner of New York City; Jeffrey Luber; and the late Sidney B. Weinberg, M.D., former chief medical examiner of Suffolk County, all of whom I met through the Suffolk County Office of the Medical Examiner, an organization that has been a continuing source of support and information. Other forensic scientists who helped me learn include Michael Baden, M.D., chief forensic pathologist for the New York State Police; the late Theodore Ehrenreich, M.D., consultant in clinical pathology to the New York Office of the Medical Examiner; Zeno Geradts, forensic scientist at the Netherlands Forensic Institute; the late Milton Helpern, M.D., chief medical examiner of New York City; and Peter D. Martin, retired deputy director of the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory, United Kingdom (Scotland Yard).

I am also grateful to the Museum of Long Island Natural Sciences at Stony Brook University, which as sponsor of the annual Forensic Forum has aided and abetted my efforts.

CHAPTER 1

Dialogue with the Dead

You can take him to the mortuary now.