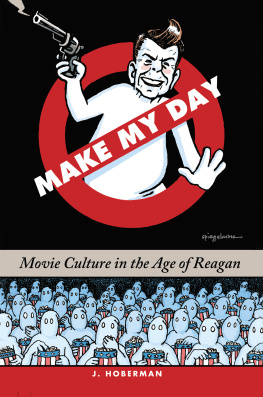

Make My Day

ALSO BY J. HOBERMAN

Film After Film (Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema?)

Found Illusions I: An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War

Rituals of Rented Island: Object Theater, Loft Performances, and the New PsychodramaManhattan, 19701980 (with Jay Sanders)

Entertaining America: Jews, Movies and Broadcasting (with Jeffrey Shandler)

The Magic Hour: Film at Fin de Sicle

Found Illusions II: The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties

On Jack Smiths Flaming Creatures (and Other Secret-flix of Cinemaroc)

The Red Atlantis: Communist Culture in the Absence of Communism 42nd Street

Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds

Vulgar Modernism: Writing on Film and Other Media

Midnight Movies (with Jonathan Rosenbaum)

Dennis Hopper: From Method to Madness

Home Made Movies: Twenty Years of American 8mm & Super-8 Films

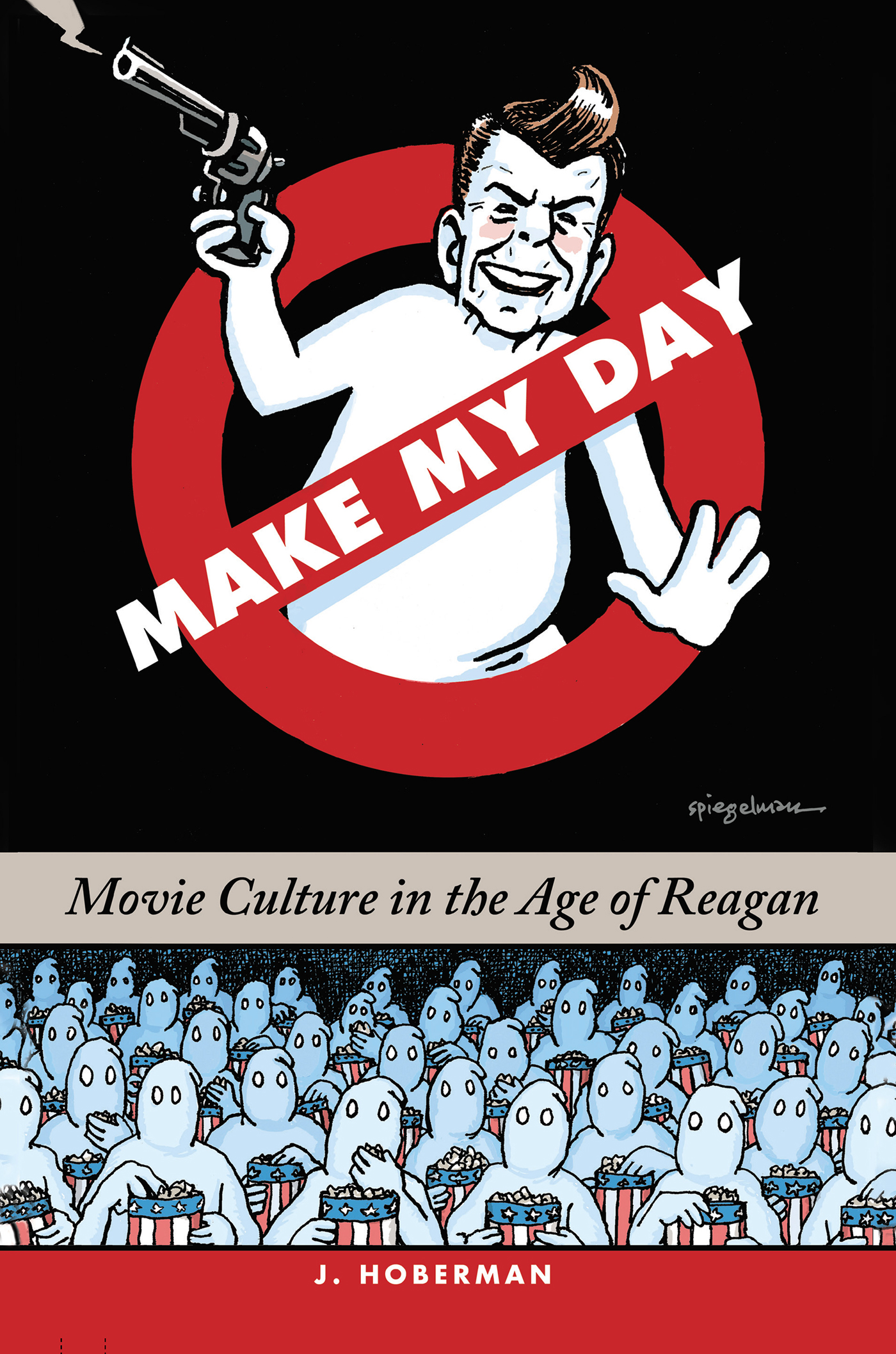

Make My Day

Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan

J. Hoberman

For Julian, Izidore, Caleb, and Elena in hope that their

generation will help America find a just future

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan completes a trilogy begun with The Dream Life: Movies, Media, and the Mythology of the Sixties (2003) and, albeit flashing back to the 1940s and 1950s, continued in An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War (2011).

These can be read in chronological order, the order in which they were written, or independently. In any case, I see them as one book, titled Found Illusions, and cherish the hope, however utopian, that they might someday be published with a common index. Readers of the first two books will see certain ideas come to fruition in the third; readers of Make My Day will find much that is prefigured in the earlier books.

Although Found Illusions was conceived long ago, I began writing Make My Day during the presidency of Barack Obama and finished it under that of Donald Trump. His presence casts a shadow over the entire book although I do not explicitly acknowledge it until the epilogue.

Because I began in the middle of the story, I did not anticipate the obvious, namely that the villainous Ronald Reagan would eventually be my protagonist. Reagan is the lone American politician, save South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond, whose career spanned four decades (although only half of them were spent holding or seeking public office), the duration of the Cold War. I believe that Frank Sinatra and Jerry Lewis, both Reagan buddies, may be the only other American pop stars with comparable longevity.

Many individuals figure in two of the three books, but the only other people, besides Ronald and Nancy Reagan, who are even marginally present in all three are JFK, Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Martin Luther King, Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Ayn Rand, John Ford, John Huston, John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Henry Fonda, Marlon Brando, Dennis Hopper, Elvis, and the fictional Davy Crockettwhich probably says as much about my sense of the period as it does about the period itself.

All three volumes reference Disneyland and the film critics Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael. That the latter became more prominent as Found Illusions continued came as a surprise to me, in that my critical disagreements with Kael are profound. The conclusion I draw is that she was the Cold Wars preeminent sociological film critica characterization she would surely have rejected, although its worth noting that by the mid-1970s, sociological analysis of Hollywood movies had become commonplace. The philosopher Jacques Ellul, author of Propaganda: The Formation of Mens Attitudes, is also cited throughout.

Make My Day is not a work of film criticism. Nor is it strictly speaking a history. I see it rather as a chronicle in which political events and Hollywood movies are folded into each other to illuminate what, writing in 1960, Mailer termed Americas dream life. Consequently I have discussed many movies that I dislike, often at some length, and omitted or minimized some that I admire. The Next Voice You Hear, High Noon, On the Waterfront, A Face in the Crowd, Bonnie and Clyde, Dirty Harry, Jaws, and Ghostbusters are not to my mind the greatest movies of their era. Rather, they are among the richest political allegories. Similarly, I have concentrated on certain genresaction films and science fictionwhich lend themselves most obviously to political readings. (Westerns, so crucial to The Dream Life and An Army of Phantoms, were all but played out in the period covered by Make My Day.) Virtually all movies discussed could have viewed by Reaganor actually were.

I believe that to some degree every movie is a documentary of its own making and I am particularly interested in how movies were received in their own time. Box office grosses aside, it is not easy to gauge initial reception. For that reason, I have relied on contemporary reviewsboth from mainstream and from sectarian sourcesto provide some sense of how they were taken by journalists and professional filmgoers. In writing Make My Day, I could not ignore the fact that, throughout the 1980s, I myself was one such professional, reviewing movies for the Village Voice, a publication that allowed me an extraordinary amount of freedom to write what and how I wanted.

Rather than paraphrase my articles and columns, I have excerpted them, sometimes in annotated form. Consequently Make My Day is a good deal more personal than its predecessorsnot least for the strong opinions I then expressed on Ronald Reagan, candidate and president.

J. Hoberman

New York City, December 2018

Make My Day

INTRODUCTION: THE DEPARTMENT OF AMUSEMENT

Film is forever.

Ronal d Reagan, March 31, 1981

Two months and ten days after his inauguration as president and on the afternoon of the 53rd Academy Awards ceremony, Ronald Reagan was struck and wounded by the last of six shots fired by John Hinckley Jr., a deranged fan obsessed with the 1976 movie Taxi Driver and its star Jodie Foster.

The Oscars were delayed for twenty-four hours but, on the night of March 31, even as the president lay recuperating in George Washington University Hospital, his image addressed the American people. After an introduction by the evenings host, Johnny Carson, who noted that Reagan had asked for a TV in his hospital room so that he might watch the show, a screen descended on the stage of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

Speaking from the White House, where he had been recorded several weeks earlier, the presidenta member of the Academy until his electionthen welcomed, on behalf of himself and his wife, herself a film actress as Nancy Davis, those fellow citizens eagerly awaiting the presentation of the awards:

Its surely no state secret that Nancy and I share your interest in the results of this years balloting. Were not alone; the miracle of American technology links us with millions of moviegoers around the world. It is the motion picture that shows us all not only how we look and sound butmore importanthow we feel. When it achieves its most noble intent, film reveals that people everywhere share common dreams and emotions.

Call it a political unconscious, a social imaginary, or simply Americas dream lifethe place where, as Greek tragedies addressed the Athenian politys primal conflicts, Hollywood scenarios and movie stars articulated the publics inchoate yearnings. Norman Mailer used the term in his account of the 1960 Democratic National Convention that nominated John F. Kennedy, predicting that the American landscape would be overwhelmed by the subterranean river of untapped, ferocious, lonely, and romantic desires, that concentration of ecstasy and violence which is the dream life of the nation.

Next page