For a number of years before he retired in 1980, the University of Bradford had, as a member of its security team, a conscientious and likeable man of Polish origin known to everyone as Michael. I knew him well in my role as Pro-Chancellor of the University and now, some years later, I have come to know him differently and better through his writings.

Michael called to see me at my home to ask if I would read the book he had written in retirement about his early life and about which he spoke with much sincerity and conviction. It tells a story which is gripping in its sense of determination and it informs the reader about facts which I recall, through having served with Polish officers and troops during the Second World War in Scotland, Palestine and Italy.

I have heard many stories of escapes and of valour but this one by Michael surpasses all others. It is an enthralling account that will teach its readers a great deal. If its writer believes, as he says, that he owes this country gratitude, he showed it adequately by his work at the University. He was part of a very good team but I doubt if any of them really knew what he had undergone in his early years. I commend this story to the readers.

A.J. Thayre, CBE, Hon D. Litt, DL

Pro-Chancellor of the University of Bradford

Former Chief General Manager and

Director of the Halifax Building Society

Former Lieutenant-Colonel, the Highland Light Infantry.

Michael Krupa lives in a village near the city of Bradford in West Yorkshire. Bradford is home to thousands of people like him of Polish and other East European descent. Many of the Poles among them were forced from their homes during the Second World War by the Soviet authorities, deported to the Soviet Union, eventually released under the terms of an amnesty concluded between Stalin and the Polish Government-in-Exile in London and finally allowed to leave for Persia. Many of the males joined the Polish military forces in North Africa or Great Britain and took a courageous part in the liberation of the European continent from the Nazis.

After the war most of them settled in Britain and were joined by others from camps in Germany. Women and children who had spent the war in parts of the British Empire away from the fighting were also brought to Britain at this time. The worsted textile industry of the Bradford area offered a ready means of employment at a time when many occupations were closed to them.

Although there was a common pattern to the experiences of many of the refugees from the Soviet and Nazi dictatorships, there are many variations in detail and each person has his or her own distinctive story to tell. For most of them there is enough experience of terror, hardship, semi-starvation, brutality, fear and loss compressed into a few years to last a lifetime.

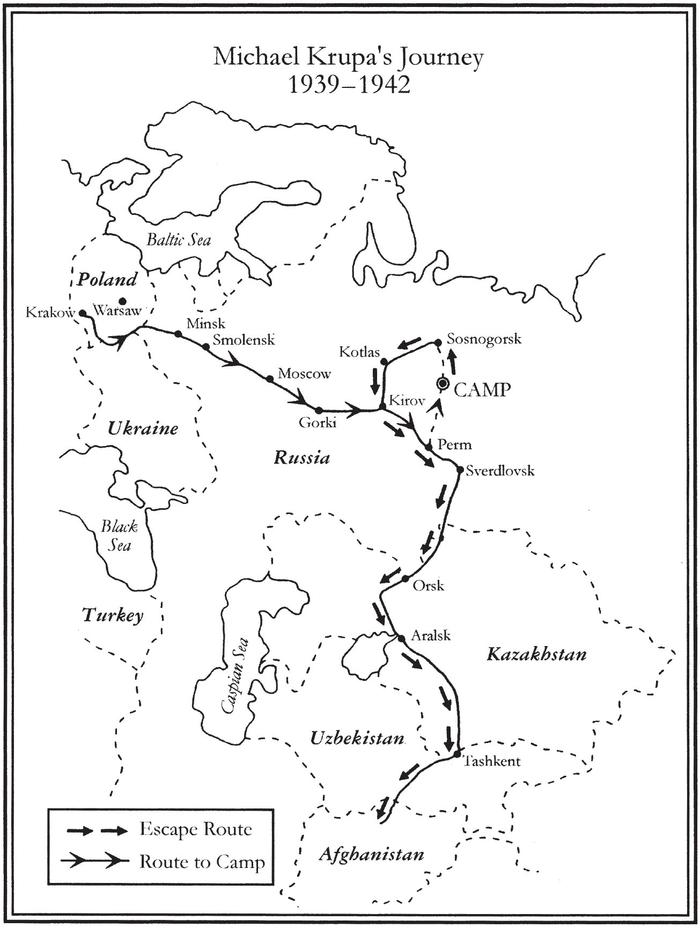

Michael Krupas story falls outside the common patterns, however. He was not part of the four mass deportations of Poles to the Soviet Union in 1940 and 1941. He was not part of the amnesty agreed between the Soviet and Polish authorities in July 1941. He did not get out via Persia. As an alleged German spy, he was subjected to brutality and torture in Moscows infamous Lubianka prison. As an ex-Jesuit monk, he had the spiritual strength to survive the monstrous treatment meted out to him and other prisoners. His is a rare example of a man who escaped not from one, but from two closed societies, the Jesuit Order and the Soviets. It is not surprising that freedom is the dominant motif of this book.

In many respects, of course, Krupas account of his experiences in Stalins Soviet Union epitomises that of millions of others whose lives were destroyed by the prisons and labour camps of the NKVD or its successor, the KGB. The fate of these wretched victims of a barbarous system was once shrouded in mystery. Now, however, the few early accounts have been supplemented by a steady stream of memoirs from those who rather miraculously survived their incarceration. The greatest debt both of the survivors and of posterity is owed to Alexander Solzhenitsyn whose work TheGulagArchipelago used the testimony of thousands of fellow-victims of the camps to build up an exhaustive account and indictment of the Soviet penal system. The Soviets created nothing less than an organisation for the mass production of terror and punishment which preceded that of the Nazis and lasted much longer.

Why publish yet another account of these events? There are, in my view, several compelling reasons for doing so. The first is that Krupa was born in Poland and, unlike most Russians who entered the camps, had experience of a relatively free society between the wars. This provides him with a rather different perspective on Soviet organs of repression from that of many Russians and a greater, if unreasonable, confidence that he might escape and survive. Secondly, this book is not only about Soviet camps and prisons, though it provides additional evidence about them. It is about the contrast between oppression and freedom, about a young Polish mans obsessive determination to be free from the slavery of oppressive institutions, first from the Jesuit order, then from the Soviets. The experience of the first, it may be said, strengthened him in his confrontation with the second.

Again, for Michael Krupa, almost uniquely, the camps were not the literal and metaphorical terminus at the end of the line, as they were for most inmates, but a station enroute during an epic journey of thousands of miles from southern Poland to Afghanistan through the heart of Stalins Russia during the Second World War. Of course, other Poles and other Russians were released from camps under amnesty, either after the signing of the PolishSoviet agreement in July 1941, or after Stalins death in 1953. As an alleged spy, Krupa was not eligible. Unlike them he escaped; unlike most other escapees he survived. This was a remarkable feat and deserves to be recorded. From my own experience of interviewing many Poles in Britain, I know that Michael Krupas story is out of the ordinary and parallels only in part the general experiences of Polish deportees.

His account of these events, furthermore, is not a sober, understated resum, nor is it an extended reflection on the nature of the Soviet system. It is, by contrast, an adventure story which carries the reader along from one tight corner to another, from one grim experience to the next, leaving us marvelling at the capacity of the human spirit to survive in terrible adversity. Unlike most adventure stories, however, this is not fiction; indeed in some respects it is stranger than fiction. This is the story of one man who beat the system against overwhelming odds, in the full awareness that the system would have devoured him if he had made a mistake. Its fascination lies in the contest between a lone figure and one of the most effective punitive machines ever devised by man.

However, Krupa is not superman. He is very human in his vulnerability and weakness; he made one major mistake and, like everyone else in such circumstances, was about to pay for it with his life. But at this point he enjoyed a tremendous stroke of good fortune and miraculously survived, avoiding the shallow grave in Siberia to which his body should have been consigned.

However, if Krupas work may, in some respects, be described as a thriller, it is not one that can be enjoyed in a superficial way. One becomes engaged with his humanity and admires the qualities of mind and character which enabled him to survive against overwhelming odds. He would be the first to admit, however, that luck, as well as good judgement and courage, were on his side, not once but on several occasions.