PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

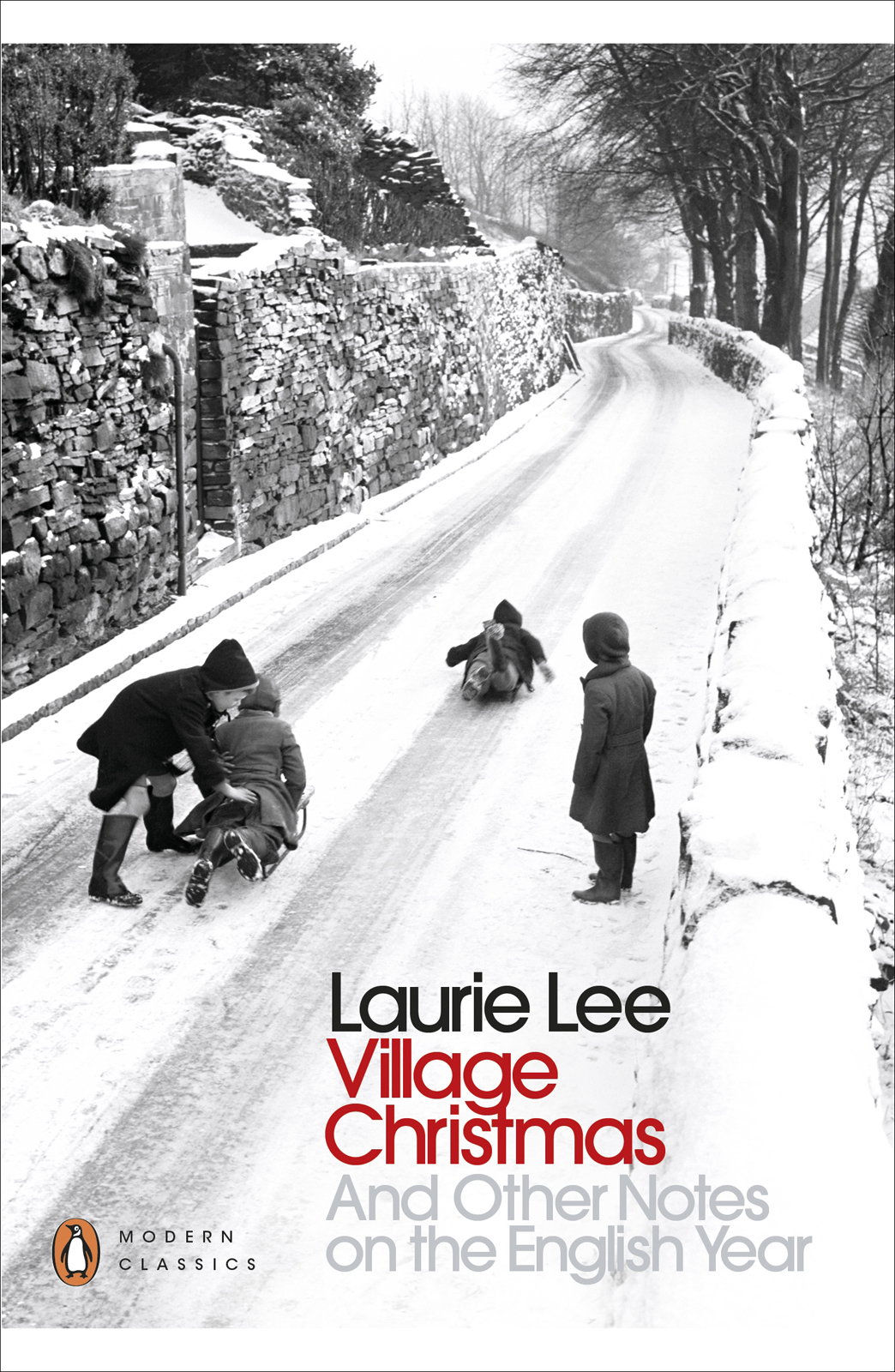

VILLAGE CHRISTMAS

Laurie Lee has written some of the best-loved travel books in the English language. Born in Stroud, Gloucestershire, in 1914, he was educated at Slad village school and Stroud Central School. At the age of nineteen he walked to London and then travelled on foot through Spain, where he was trapped by the outbreak of the Civil War. He later returned by crossing the Pyrenees, as he recounted in A Moment of War.

Contents

Laurie Lee

VILLAGE CHRISTMAS

And Other Notes on the English Year

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Penguin Classics 2015

Published in paperback 2016

This collection copyright The Trustees of the Literary Estate of Laurie Lee, 2015

My Day copyright Laurie Lee/Vogue The Cond Nast Publications Ltd

Cover photograph: John Gay/English Heritage/Arcaid/Corbis

ISBN: 978-0-241-24368-8

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

Notes on England

To most of us, England is a green sweep of heraldic history marked here and there by the black thumb of coal. The bit I know best is local and enduring, has little history and almost no official heroes.

I was born in a corner of the Cotswolds an odd lozenge of land centred round the small town of Stroud, cluttered, iridescent but unchangingly beautiful, comprising a bit of swampy plain, fine secretive valleys and a brooding ridge of bare hills stretching away to Wales and to the blue Wenlock Edge.

I was nineteen years old when I first left my home ground, where all of us at that time, family and neighbours alike, had seemed happily and tightly wedged. Ah, the Cotswolds, people said, when I got to London. Stow-on-the-Wold, Bourton-on-the-Water, Burford, eh? I didnt know any of them. They might as well have been in Lapland. People in our valleys seldom budged very far.

Stroud, Slad, Sheepscombe, Painswick, Bisley, Miserden, The Camp these were the Cotswolds we knew, the limit of our contentments.

What I loved, and still love, about that small pocket of England was that it was odd, radiant and unlike anywhere else. So static, indeed, and immovable, that our staying put within its boundaries seemed to magnify the qualities of where we were, so that it seemed natural to know every blade of grass, each stone and roof tile.

Our bit of country, because of its extremes its slopes, shadows, oblique angles of light, deep woods and high open fields seemed also to separate and dramatically magnify the seasons, the winter landscape locked up with a giant key, great snowdrifts arriving like the tents of Attila; spring too pretty by half with sudden shining streams and beech leaves like fresh-washed salads; summer, a brown exhaustion of baking wheat with cows lying in brown mud round the edges of ponds; and autumn, a fermentation of all that had gone before.

Were these seasons remarkable or did they happen elsewhere? To me they happened only at home. And happening in that place, at that time, have become a reference for all seasons, everywhere, whenever I pause to think of them.

As do those sudden outbursts of oceanic storms, western gales blowing in from the Atlantic, with sheep huddling in bunches, bushes bent to the ground and chimneys toppling, and birds flying backwards; so perpetual were those winds funnelling up my valley that Id swear, at times, I could smell New York three days old and the overnight street of Cork.

This bit of England was also a country of seepages, shaped and populated by them; seepages from the melting glaciers, the rivers and estuaries, up which my neighbours had arrived in their canoes and coracles, settling, raising cattle, building walls, digging holes, becoming miners, shepherds, weavers. Hogg, Webb, Wynn, Jones; you scarcely needed to open your mouth to speak such names, and with jobs like theirs you didnt move about much. A damp green place this, small and domestic in scale. But the citizens know its measure.

The expansive oddity of this district is that it breaks into three the high, flat sheep-hills, the valleys dropping to the plain, then across the Severn westward to the black-eyed tribesmen in their forest, each with a private coal mine at the bottom of his garden.

On my side of the river, in spite of the rapid spread of houses and factories muzzling up the valley slopes, you will still see wild animals, in sudden flashes of light, the bright stoat, stumbling badger, the diamond eyes of pheasant and fox; and occasionally, rarely, a red deer fleeing like a curates daughter.

But overall, it is the scale and timelessness I love the unblown mystery of this part of England. Trunk roads, TV masts, Berkeley Nuclear Power Station, yes; but behind us, where the escarpment runs like a long cliff above the plain, up there, outside the villages and above the towns, the little tumps and hillocks still stand in the grass. For three thousand years, the axe, the spade and the plough have carefully circled them and left them untouched.

And beneath the turf they still lie, and we know who they are grandfathers of our grandfathers whose hazed existence has been carried forward on the living breath of mother to child the local bronze-age chiefs, squint eyed and laconic, who you still see throwing darts in the pub.

WINTER

Village Christmas

Christmas today often falls far ahead of its time, with signs in the shops appearing soon after the summer holidays. But in my childhood, Christmas began at the proper season, only just before the Feast itself.

For us boys in our village in the Cotswolds, it always started on a star-bright night, never prearranged but intuitively recognized. A few of us would wrap ourselves in scarves and mufflers, fix lighted candles in jam jars and go through the streets calling out the rest of the gang. Comin carol-barking, then? It was a declaration, not a question. One by one they appeared, flapping their arms and stamping their feet.

We were a ragged lot but we had official status, for we were the boys of the village choir, and as a reward for a year of dutiful churchgoing, wed earned the right to sing carols at all the big houses in the valley, and collect our tribute.