Copyright 2013 by Lucy Lethbridge

First American Edition 2013

First published in Great Britain under the title Servants: A Downstairs View of Twentieth-century Britain

Photograph credits for the insert, in order of appearance, are:

1. National Trust; 2. Private Collection; 3. Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images; 4. English Heritage; 5. Barnardos; 6. Getty Images; 7. Universal Aunts; 8. Reproduced with permission of Punch Limited; 9. Public domain; 10. The Advertising Archive; 11. Getty Images; 12. Getty Images; 13. The Wiener Library; 14. Getty Images; 15. Getty Images; 16. Public Domain.

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Production manager: Devon Zahn

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Lethbridge, Lucy.

Servants : a downstairs history of Britain from the nineteenth century to modern times / Lucy Lethbridge. First American Edition.

pages cm

Originally published under the title: Servants : a downstairs view of twentieth-century Britain.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-24109-9 (hardcover)

1. Household employeesGreat BritainHistory20th century. 2. Household employeesGreat BritainAttitudes. 3. Social classesGreat BritainHistory20th century. 4. Great BritainSocial conditions20th century. I. Title.

HD8039.D52G7766 2013b

331.761640941dc23

2013028069

ISBN 978-0-393-34980-1 pbk.

ISBN 978-0-393-24195-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For my parents, and in memory of Blanche Hole

I n 1901 the Earl of Derby, viewing the prospect of hosting the new King, Edward VII, and forty of the Kings friends at Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool, was overheard to say of the arrangements the visit would require: that makes sixty extra servants and with the thirty-seven who live in, nothing could be simpler... Entertaining on such a grand scale was the very fabric of Edwardian country house life; in many cases, by the turn of the century, after mid-Victorian agricultural depressions had caused a sharp decline in the value of farming land, lavish entertaining was even its raison dtre . Lord Derbys quota of thirty-seven indoor staff was hardly excessive for the times: the Duke of Devonshire found that two hundred servants were the barest minimum necessary to look after the needs of a house party of fifty people.

The idea of the perfect servant silent, obsequious, loyal is a central component of the many myths of Englands recent past; servants underpin the ideal, never quite attainable, of a perfectly ordered life. Tracing the classes down through their many gradations, we find servants at almost every level except the very poorest. In 1911, 800,000 families in Britain employed servants, but only a fifth of them retained a staff of more than three; the vast majority were served by a single domestic, very likely a girl in her early teens, someone like the poor skivvy described by H. G. Wells in Kipps , who has to go up and down, up and down and be tired out. Yet, as people in their own right, servants remain elusive. For the researcher into domestic service, they emerge in tantalising glimpses, mentioned only in passing in the memoirs or autobiographies of their employers, or given comic working-class characteristics. They were witnesses at first-hand of vast social changes but rarely were they able to be active participants; they were adjuncts of the action rather than shapers of it.

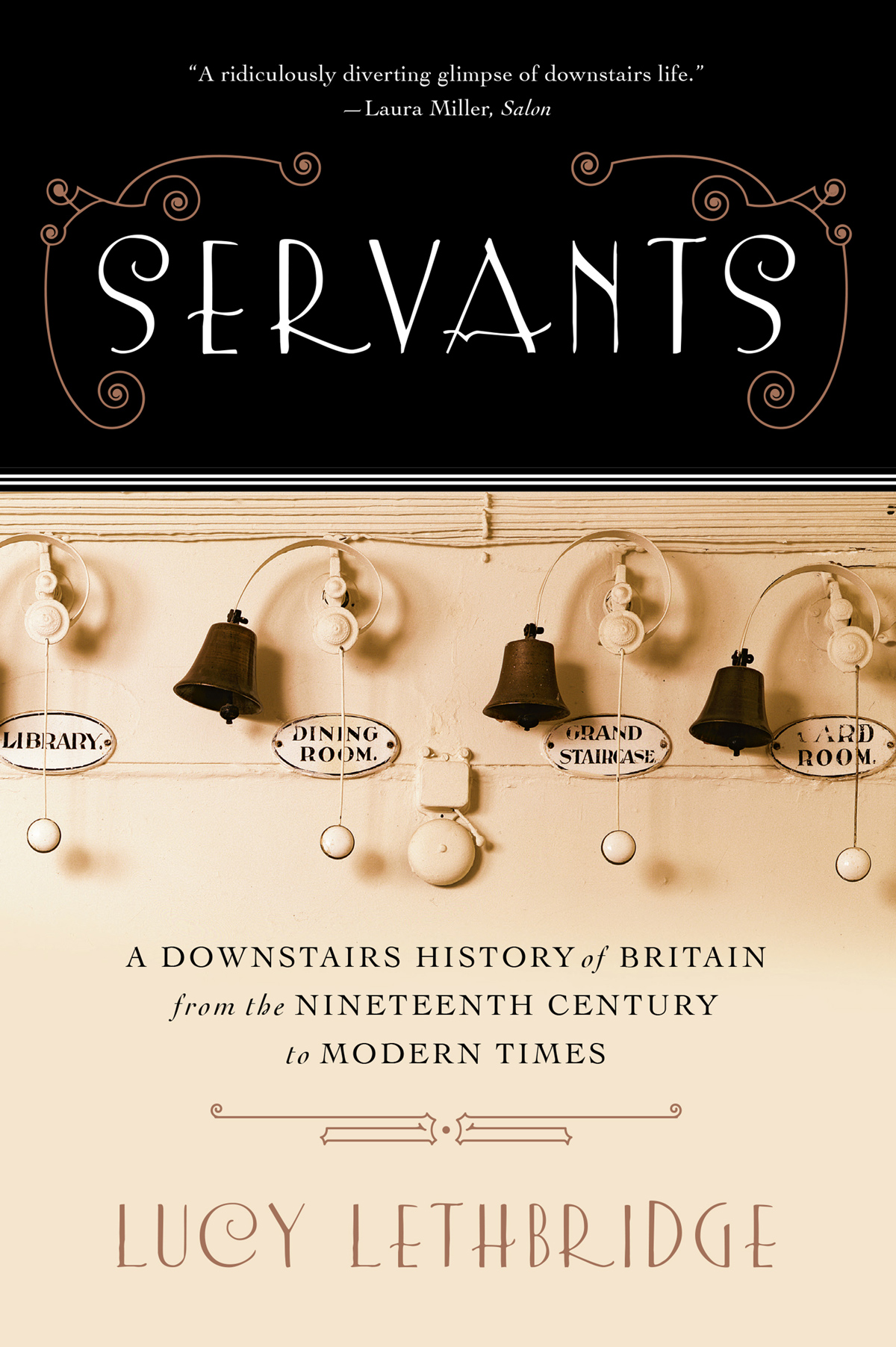

From the mid-nineteenth century to our own day, the relationship has been difficult to pin down. With starched uniforms, green baize doors, electric bells and separate servants quarters, the Victorians reinforced the separation between the domestic workings of a home and the sanctity of the family at its centre. The relationship between the server and the served became the often-resented demarcation of below stairs and above. The author and politician Christopher Hollis, writing in 1929, thought that the inequality between servant and master which beleaguered so many British homes was a special vice of Victorian England. The Continent has never properly had it. The Middle Ages certainly did not have it. The Shakespearean masters and servants knew nothing of it, nor did the masters and servants of Sir Walter Scott. In the seventeenth century the Pepys sent for their servants to join in their games as a matter of course... Below the surface of the social changes of the twentieth century, this inequality, right at the heart of the family home, began to chafe.

Yet servants also squeeze awkwardly into the big narrative of twentieth-century labour history. Despite the great numbers of working-class women employed as domestics, servants have been viewed as standing outside working-class political movements. Although service, particularly in large country houses, was often seen as a way of gaining protection and patronage, career servants were despised by members of their own class as flunkeys, propping up a hated system of privilege and dependency. As the butler John Robinson put it in 1890: The paralysing influence of the servants environment has prevented his calling very loudly for more freedom. It was as if the demeanour of servantliness, once assumed, was impossible to shake off. No wonder employers and domestic advice manuals stressed the innate nature of the good servant, the spiritual communion between hard domestic labour and Christian virtue. As the 1853 manual Commonsense for Housemaids suggested: A really good housemaid should never be able to be alone in a room with a table without giving it a good rub, or, if the room is occupied, without wishing to do so. Tables and chairs should be to her objects of deep interest; after her own family and the family of her mistress, they should claim the next place in her affections.

Housework, to that paragon of 1930s fictional femininity, Mrs Miniver, was properly intended to be the low distant humming in the background that allowed Mrs Miniver not only to take her place in the world but to concentrate on the interesting complexities of her inner life those complexities that only freedom from humdrum domestic labour could facilitate. The having of servants was a precondition of much that has been considered important in all the classes: ceremonial, tradition and leisure for the upper classes; status, hygiene and respectability for the middles; the conspicuous consumption of goods and leisure that marked an age of industrial wealth.

In this book I have gathered together voices, heard and unheard, published and unpublished, of domestic servants. Every example of oppression and ill-treatment on the part of employers can be countered by another of reciprocal friendship and loyalty. Some servants were crushed by the experience, others were rebellious, some were proud. Their accounts are testaments to personalities that were often given little room to shine in their own right but were witnesses of the social changes that have taken place in the British home over the last century: changes in the way we live, in the way we run our homes and our attitudes to family, money, work and status.

Next page