Old-fashioned Ways to Banish Dirt, Dust and Decay

LUCY LETHBRIDGE

For Sarah Cole, whose idea it was

CONTENTS

Domestic business is no less demanding for being less important

Montaigne

In 1900, general housework in the British home was so labour intensive that it required a workforce of servants to implement it. This in turn entrenched a hierarchy of exacting standards of cleanliness, etiquette and order that made it impossible for the middle-class family to imagine being without domestic help. Taking their inspiration from the upper-class country household, with its fleets of uniformed and liveried retainers, middle-class homeowners financially crippled themselves to afford even a single maid rather than suffer the ignominy of doing their own housework.

The more furnished, padded, well stocked and decorated homes became, the more housework they generated. A profusion of cheap, factory-made fabrics resulted in more laundry, more furniture meant more dusting, the increase in available foodstuffs meant elaborate meals and more washing up. The outside world was dirtier (or rather the dirt, in the form of dust, smuts and mud, was more visible) than it is today. Geoffrey Brady, who was born in 1898, lived in an affluent suburb of Stockport. He remembered the constant labour of the familys servants: If you had your windows open for quarter of an hour you had to go round with a duster afterwards to clean up the smuts and things like that. Curtains were being washed continuously and ones clothes and handkerchiefs were quite filthy by the end of the day.

Technology has followed domestic labour, finding ways to speed up and alleviate household tasks. By the 1880s, there seemed to be a device, with varying degrees of real usefulness, for every requirement. No matter whether we desire to clean knives or make stockings, peel potatoes, black shoes, make butter, wash clothes, stitch dresses, shell peas or even make our bread, all we have to do is turn a handle. This is a regular handle-turning age, wrote a correspondent in the 1882 Journal of Domestic Appliances. Mangles, knife-cleaners, boot-polishers, dishwashers, vacuum cleaners all these reduce the labour of the business of keeping clean; though it is interesting to note that machinery sometimes actually expands the number of hours put into housework. Washing machines enable us nowadays to wash our clothes a great deal more often than the old days when there was one weekly laundry.

Advances in household technology vied with a longer-standing resistance to the idea of labour-saving. Work was morally uplifting particularly when you werent the one doing it. Old-fashioned servants remembered how employers looked for signs of physical labour and suffering as indications of a job well done. Now Edith, youre getting lazy, admonished Edith Halls employer in the 1920s, when she wanted to use a soapy water wash for cleaning the floor rather than the harsh soda and water concoction that hardened hands and burned the colour off the linoleum. However, for many others the rise in popularity of new branded detergents and household cleaners such as Sunlight and Lifebuoy gave a whole new definition to the meaning of clean. It was not enough for an object to simply be without a coating of dirt now it had to smell of the powder it had been washed in.

Following the technologies available to us, our idea of everyday cleanliness has changed radically over the last hundred years or so. Few people now would think it extravagant to change their clothes every day or to take a daily bath but they probably only rarely wash their skirting boards or dust down their books. The piney, lemony smells of detergents can mask any nasty odours and a quick spray round the kitchen with a disinfectant or an anti-bacterial liquid feels as though it has probably done the business regarding lurking germs. Our kitchen tables and surfaces, covered in Formica or some other easy-wipe sealant, are far easier to keep clean than the daily scrubbing of stained and pitted pitch pine tables that was the lot of the kitchen maid.

Nevertheless, we can still learn much from the old-fashioned household skills employed by career servants. No Edwardian maid would have been stumped by a wax-covered brass candlestick or a dirty, faded rug. The chemical components of a housemaids cupboard seem today like a terrifyingly toxic laboratory. In fact, a few basic components either acid or alkali, depending formed the basis of almost all cleaning. It is quite unnecessary to buy a special bathroom spray to protect against mildew if you have a bottle of white vinegar to hand which will do the job just as well for half the price. Tea leaves for sweeping carpets, lemon juice for cleaning copper, boiling water and bicarbonate of soda are some of the basic ingredients that once cleaned a house. In this book I have gathered nearly two centuries of cleaning tips from the memoirs of servants themselves, from housekeeping guides and advice manuals. This book covers every corner of the house, from dusting ceilings to clearing drains and getting rid of cockroaches. The best and simplest of older methods still work for us today and in many cases their modern equivalents are simply variants of them. These tips are, for the most part, quick; they are also cheap, environmentally friendly and effective.

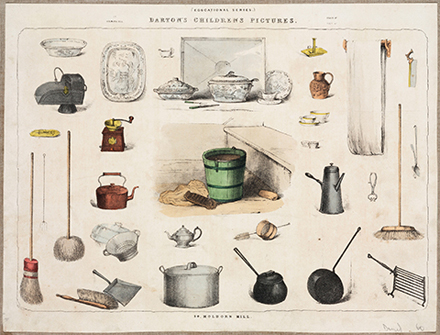

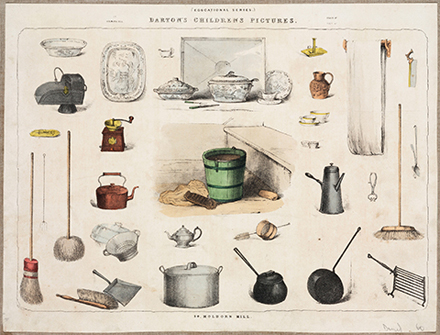

The omnium gatherum of the house

J. B. Alden, 1880

An impressive variety of ingenious materials have been used for cleaning over the centuries. The average cleaning cupboard today will probably contain little more than a vacuum cleaner, some kind of mop and a broom; maybe also a few dusters and some liquid cleaning solution. But a century ago, a household cupboard, even in a modest home, would have contained a piece of equipment for every conceivable domestic task all arrayed in the orderly manner recommended by Mrs Beeton in her first Book of Household Management.

The authors of manuals of servants duties always stress the importance of the tidiness and order of this cupboard. It was, as Mrs Beeton put it, where perfect order should prevail: it was seen as a reflection of the order of the house, and therefore of the psychological order of its occupants. The housekeeper had charge of cleaning materials in larger homes, and in smaller houses, the housemaids closet, usually on an upper landing, was the centre of operations. This sometimes had its own supply of soft water pumped in from the outside. Most housekeeping experts recommended that the closet contained a small copper (a built-in copper-lined container with a fire beneath it for boiling water). Generally found near the servants bedrooms on the top floor, the closet also usually contained a sink where the contents of the households chamber-pots were disposed of every morning. The surrounding area therefore tended to be, as the