First published in 1962

This edition first published in 2011

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1962 T.C. Lethbridge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-61927-1 (Set)

eISBN 13: 978-0-203-81784-1 (Set)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-60460-4 (Volume 6)

eISBN 13: 978-0-203-81903-6 (Volume 6)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

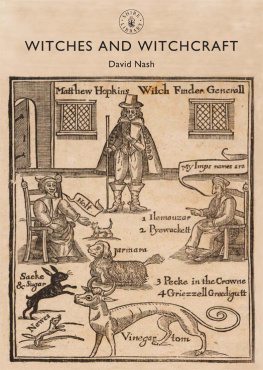

WITCHES

Investigating an Ancient Religion

by

T.C. LETHBRIDGE

First published 1969,

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

Broadway House, 68-74 Carter Lane

London, E.C.4

Printed in Great Britain

by Western Printing Services Ltd

Bristol

T. C. Lethbridge 1962

No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form without permission from

the publisher, except for the quotation

of brief passages in criticism

Preface

There is really only one study of man, and this should be known as Anthropology. Medical Science, History, Archaeology, Folk Lore and the rest are all branches of the one study. But this present age is one of specialization and all these branches are tending to become so elaborate and, at the same time, so constricted that we are in need of trained middle-men, who have a wide enough grasp of all of them to be able to pull the whole thing together and present it in readable form to those who wish to learn. These middle-men really do not exist today, for there is no training to fit them for the task. The Scottish university system is much better than the English in this respect; but even there the scope of training could be wider.

After watching the steady growth of specialization for many years, sometimes when sitting in considerable boredom on a Faculty Board at Cambridge, it seemed to me to be something of a duty to spend as much time as possible trying to pull together some of the information which is being scattered among different studies. To this I add my own ideas and speculations, in the hope that the resulting pottage may be of general interest and even perhaps of some value.

As I sit at my desk here in Branscombe and look over my left shoulder, I can see the sea through a gap in the wooded ridges. Sometimes fog shrouds it and at other times it is blotted out by driving squalls of wind and rain. But all the time I know that it is there and with that knowledge I am content.

For several thousand years that sea has been the only road by which men and ideas could come to Britain and the very crossing of that sea has always carried an element of risk and change. No idea has ever come to rest in Britain which has not been changed in the process, and it has been the same with religious ideas as much as with any others. Therefore we must not expect to find that our old concepts were exactly the same as they were on the continent of Europe. We must also find that we have to experience a certain amount of discomfort if we are to learn about them at all. The discomfort in this study lies in the inordinate number of unfamiliar names with which we have to cope. I know that these may be boring to readers and I would avoid the use of them if I could, but it is impossible. I have reduced them as far as I dare to do so. But, just as in the seamans trade it is necessary to learn a new, but simple and effective, list of words, so this is necessary in the study of an old religion to compare it with others. For this comparison one must use the names of the gods and goddesses which belong to them. Therefore no apology is really needed and if readers find these names difficult and boring they must understand that I have done my best to simplify matters. I am the last person to introduce unnecessary names or terms. I leave these when possible to pedagogues.

I need not say much more by way of introduction. The witches themselves have been kind and helpful; but, after hundreds of years of persecution, no one ought to expect them to give themselves away. I have deliberately avoided prying into secrets which they may wish to keep. The subject, however, is of great general interest and in many ways I think they have been wickedly wronged. No study of religious history in Britain can be even approximately correct which does not attempt to evaluate their beliefs. They obviously represent the oldest form of rationalized religion which still exists. One can hardly describe totemistic beliefs as rational.

With this introductory warning, let us cut the cackle and come to the horses; there are many in this story.

My wife, as on many former occasions, has been of the greatest help with this study. I think she has found it more interesting than most of my efforts and perhaps this is some slight recompense for her hard work in typing it out.

T.C.L.

Diana and her darling crew shall pluck your fingers fine,

And lead you forth right pleasantly to sup the honey wine.

To sup the honey wine, my loves, and breathe the heavenly air,

And dance, as the young angels dance. Ah god that I were there!

(Apparently a sixteenth-century version of a hymn to Diana. It is sung to the tune of Jerusalem my happy home, a tune which may well have belonged to it in the first place.)